The English colonists in Massachusetts were sometimes conflicted with regard to Indians. Many colonists, viewing the New World as a wilderness, felt that Indians impeded civilization and like other wild animals, such as wolves and coyotes, should be exterminated. There were also a few who viewed Indians as potential souls to be harvested in the name of their religion. With regard to religion, historians Robert Utley and Wilcomb Washburn, in their book Indian Wars, report: “A few pious remarks were made about introducing the Indian to Christianity, but there was little real missionary zeal.” The royal charters always mentioned the obligation to bring Christianity to the “savages.”

For the English Protestants, conversion to Christianity required more than a simple baptism and a profession of faith. To be Christian required living in an English-style house, wearing English-style clothes, speaking English—in other words, becoming English. The English-speaking Christian missionaries felt that the Indian gender roles must be changed to fit the colonial norms. They were offended by the fact that Indian women did the farming, were in control of their own sexuality, and had freedoms which English women could only dream about.

English policies toward Indians were based on segregation. Initially, the rationale for this segregation was based on religion: the English were Christian and the Indians were heathens. As some Indians converted to Christianity, however, the rationale for segregation became less valid. Historian Frances Jennings, in his book The Creation of America: Through Revolution to Empire, reports: “Race, identified by skin color, became a more satisfactory means of making essential distinctions.”

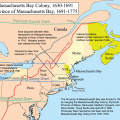

The English colonial policy of segregation and the Protestant concept of conversion requiring complete assimilation came together in a plan that called for Christian Indians to have their own separate, English-style towns. In 1651, Puritan missionary John Eliot received from the British Crown 2,000 acres of land so that Christian Indians could build an English-style town. The site straddled the Charles River 18 miles upriver from Boston.

John Elliot, who was sometimes called Apostle to the Indians, believed that Indians were descendents of the Jews who had been led to America by Satan. Indian salvation, according to Elliot, required them to embrace the moral philosophy and practices of the Puritans.

Waban, the leader of the Massachusett village of Nonantum, made the request for the new village. Waban’s reluctant embracing of Christianity was based on two primary factors: (1) he was afraid that the English would kill him if he didn’t pretend to embrace their religion, and (2) they provided him with good food.

The new town called Natick, whose name means “the place of seeking,” is a sacred place and well-suited for vision quests and dances. Unknown to the Christian missionaries, the new Christian town was strategically placed within traditional sacred geography.

The physical layout included an English-style meetinghouse, fort, and arched footbridge across the river. While lots for houses were laid out for nuclear families, most of the Indians erected traditional wigwams rather than English clapboard houses.

The Christian Indians, who came from several different tribes, adopted English-style clothing and English hairstyles as a way of demonstrating to the English that they were walking the Christian path of righteousness. The Indians adopted a legal code based on a biblical prototype which outlawed many traditional practices, including premarital sex, long hair, and cracking lice between the teeth. Penalties for breaking the rules included fines and flogging.

In 1660, Puritan missionary John Eliot claimed that 100 of his Natick converts were now literate. Elliot translated the Bible and other works into the Massachusett language and had these distributed among his converts.

In 1675, many English colonists felt that all Indians were involved in King Philip’s War even though many groups, particularly the praying villages such as Natick, had declared their neutrality. The English colony confined all “friendly” Indians to a few of the eastern praying towns and the colonists confiscated the crops and tools in the praying towns of Wamesit, Hassanamisset, Magunkaquag, and Chabanakongkomun. The Indians were confined to the village limits on penalty of death.

The colonists, however, continued to accuse the Christian Indians of supporting King Philip (whose Indian name was Metacom).The Natick were forced from their homes and interred on Deer Island in Boston Harbor. The Punkapoag were also sent to Deer Island.

The setting is generally described as a “windswept bit of rock” with little fuel and little shelter from the cold sea wind. Historian Daniel Mandell, in his book Behind the Frontier: Indians in Eighteenth-Century Eastern Massachusetts, notes: “Despite English hostility and abuse, Indian men on the island clamored to help in the war against Metacom, showing their deep loyalty to the Christian colony, an older dislike of the Wampanoags, or perhaps a strong desire to escape the conditions of the island.” About 100 men enlisted in the colonial army as scouts.

In 1677, the General Court ordered that all Indians be settled in four praying towns: Natick, Punkapoag, Hassanamesit, and Wamesit. The Indians in these towns were prohibited from entertaining “stranger” Indians and the Court ordered that a list of all inhabitants of the praying towns be made annually. When leaving the towns, the Indians were required to have a magistrate’s certificate proving their loyalty. When approached by an English person, the Indians were to lay their guns on the ground until the English had examined their papers.

In 1680, an English farmer bought 50 acres from two Indians living in the Christian Indian village of Natick. The sale was without the consent of the town council and in violation of colonial law. The Englishman then altered the deed to 500 acres. The village then sued, won, and recovered 400 acres. In other words, the farmer who bought 50 acres fraudulently wound up with 100 acres.

In 1682, a group of Nipmuc under the leadership of Black James left Natick and traveled southwest where they resettled at Chabanakongkomun.

In 1690, the General Court ordered all Indians in the Bay Colony to go to Natick or Punkapoag. The order was in response to the war between the English and French and the French Indian allies, and the fear that it would be difficult to discern between friends and foes.

In 1690, Natick minister Daniel Takawampait replaced John Elliot as minister to his people. At this time Indian leaders, including ministers, had to be approved and supervised by colonial officials appointed by Massachusetts Bay Colony magistrates. All laws and ordinances enacted in Indian communities also had to be approved by colonial authorities.

In 1698, the English town of Dedham stole 1,400 acres from the bordering Christian Indian town of Natick. The stolen land included orchards and corn fields.

In 1707, the Christian Indian community of Natick began holding the annual election of town officers, following the pattern of its English neighbors.

In 1715, the New England Company asked the Natick to sell them the apparently abandoned praying town of Magunkaquog. The Company proposed to rent out the land to English settlers and share the rent money with the Natick families. The Natick, however, were still growing crops in the area and had deep emotional feelings about the area. Magunkaquog means the “place of the giant trees” in reference to the great trees – oak and chestnut – which were found in abundance in the area.

After initially rejecting the offer, the Natick agreed to the deal. After signing the deed, one of the signatories, Isaac Nehemiah, commited suicide by hanging himself with his belt.

In 1719, the Natick created a proprietorship – a corporate entity to govern land allotments. The 20 proprietors – 19 men and one woman – were the heads of long established families. The proprietorship provided secure land titles and boundaries under colonial law which was seen as useful in meeting outside pressures. According to historian Daniel Mandell: “But the Natick proprietorship undermined the native community by severing landholding from the town polity and bringing the native community into a closer orbit to the province’s legal and economic systems.”

In 1738, the Natick complained that a mill dam on the Charles River was preventing them from taking fish. There was no response to their complaint.

In 1759, Natick warriors returned home from the French and Indian War bringing with them the contagious illness which had been killing the soldiers. In the space of three months, 20 people died.

By 1785, most of the Indians had drifted away from Natick, its lands having been sold off to non-Indians to cover debts.

Leave a Reply