American Indians occupied, utilized, and developed the peninsula known as Florida for thousands of years. Our knowledge of the ancient past—of Florida, from 2,000 years ago until about 1,000 years ago—comes primarily from archaeology. Unfortunately, archaeology tells the story of the past based on material remains, which means that these remains must have endured for more than a thousand of years, then be found, and finally interpreted. As a result our picture of ancient Florida is not complete, but rather a series of seemingly disjointed snapshots. Briefly described below are some of the archaeological findings from Florida from 1 CE through 940 CE.

In 1 CE, the Calusa built a 2.5 mile canal across Pine Island. The canal was 18-23 feet wide and 3.5 feet deep so that it was large enough to handle most Calusa canoes. To control the water flow in the canal, the Calusa used a series of 8 stepped impoundments which functioned like locks and a series of auxiliary channels which diverted excess flow.

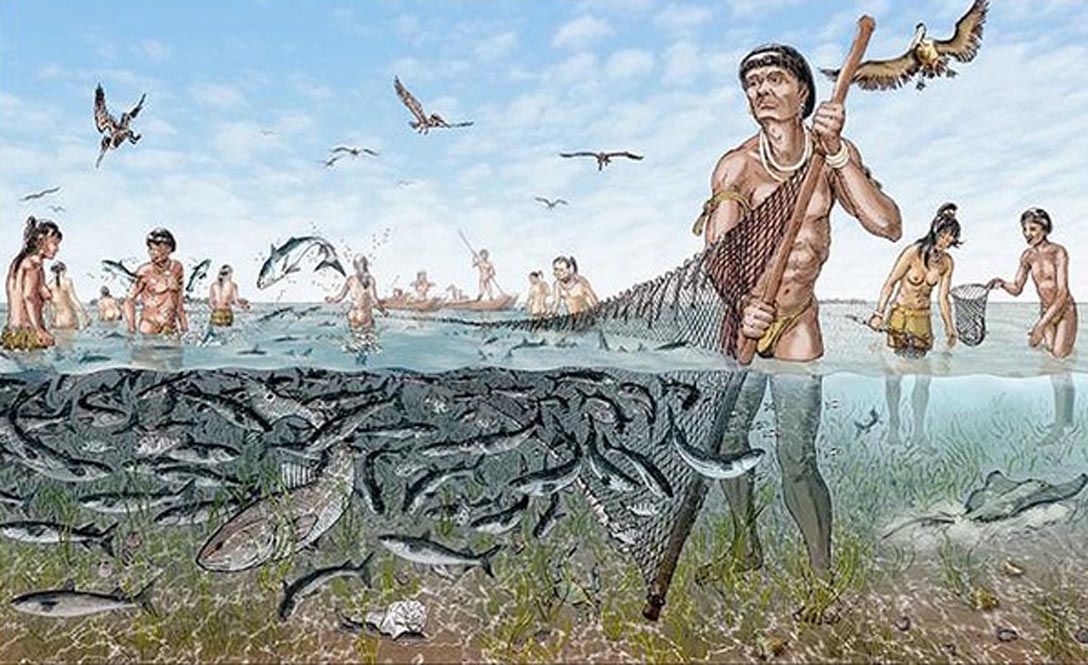

By 100, Indian people were occupying Mound Key. The shell mound which they constructed reached a height of 30 feet. Fish and shellfish provided them with a plentiful supply of food.

In 200, Indian people began construction on two canals around the rapids on the Caloosahatchee River. The canals, which were about seven miles long, facilitated fishing and transportation.

In 200, Weeden Island ceramics began to appear at the McKeithen site. The site has three mounds. Philip Kopper. in The Smithsonian Book of North American Indians: Before the Coming of the Europeans, reports: “The horseshoe-shaped, forty-seven-acre village was located on a low sandy ridge in forest-and-brush country that provided an excellent habitat for the animals and plants upon which the hunting-gathering people depended.”

The population was a little more than 100. Weeden Island ceramics also began to appear at sites in southern Alabama and southwestern Georgia.

In 300, the ancestors of the Calusa and Mayami built a seven-mile system of canals and a large pond in the shape of a baton. The canals were dug using wooden tools and shells. They were an average of 20 feet wide and 4 feet deep and provided easy canoe access to the Ortona village. In addition, the canals bypassed a series of rapids on the Caloosahatchee River.

Along the Gulf Coast area of Florida, Georgia, and Alabama, villages which were exploiting marine fish and shellfish were creating embankments in the shape of rings, horseshoes, and rectangles by the year 300. These embankments seemed to be a way for disposing refuse in an orderly manner outside of the residential area. Within the rings, the villages had a plaza and both platform and burial mounds. On the east side of the burial mounds, the people deposited groups of finely painted ceramics, many of which were effigies of humans, animals, or plants.

In 300, the Weedon Island people began occupying the Crystal River ceremonial site. The ceremonies became more complex.

In 350, Indian people at the McKeithen site began construction of two residential mounds. The mounds were planned to allow the rising sun at the summer solstice to be observed and calculated from Mound B. The two residential mounds are rectangular and fairly low—1 meter and a half meter in height. A residence was built on top of one of the mounds and a pine post screen was erected across the other. In the area behind the screen, exhumed human bones were cleaned, treated with red ochre, and prepared for storage in the charnel house. A third mound, which was circular and less than a meter in height, had a charnel house for the storage of cleaned human remains.

By 400, the Indian people of Weeden Island had developed a new level of cultural complexity and diversity. They showed social stratification in their burials, some of which now included outstanding works of pottery and carving. There was also an expansion of the population.

In 475, the structures on the platform mounds at the McKeithen site were burned and removed. The mounds were capped. While this marked the end of mound use at the village, the village itself continued to be occupied.

In the Upper Apalachicola area of Florida Indian people were raising corn and squash by 500, but were still relying on gathering wild plants and hunting for most of their subsistence.

In 600, Mound A was constructed at the Crystal River site. It was about 30 feet high and served as a temple platform.

In north-central Florida, the culture which archaeologists call Alachua began about 600. There was a migration of people from south-central Georgia who replaced the indigenous Cades Pond people. Alachua appears to be associated with the Ocmulgee culture in Georgia. Archaeologist Jerald Milanich, in his book The Timucua, writes: “the people of Ocmulgee culture may have been the ancestors of the Timucuan groups in at least a portion of south-central Georgia, but that remains very uncertain.”

In 690, Indian people began construction of Turtle Mound. The mound consisted of two connected cones which were about 35 feet high. The mound covered more than an acre and measured 180 feet by 360 feet. It was constructed from oyster shells. According to Michael Durham, in his book Guide to Ancient Native American Sites: “The mound towers over the flat terrain and possibly was used as a lookout tower by the peoples of the late St. Johns culture and their successors, the Timucuan Indians of historic times.”

By 940, a Mississippian society began to emerge in the Fort Walton area in northern Florida. According to archaeologist John Scarry, in his chapter in The Mississippian Emergence: “They were simple chiefdoms, with clear social distinctions between high status and low status individuals—distinctions revealed in residential segregation and the extraction and allocation of community surplus labor.” He goes on to point out: “The people relied on cleared-field agriculture for a significant portion of their diet.”

Leave a Reply