( – promoted by oke)

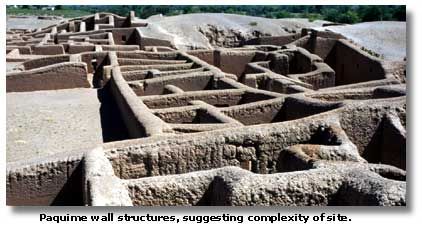

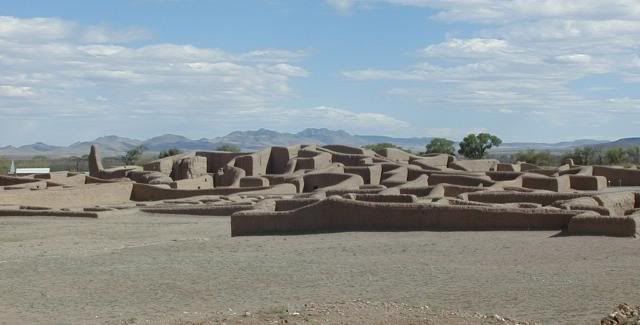

In Northern Mexico, in what is now the state of Chihuahua, the trading town of Paquimé (also known as Casas Grandes) developed and blossomed between 1150 and 1450. The people of Paquimé were more closely affiliated with the Mesoamerican civilizations to their south than to their North American Southwestern neighbors-Mogollon and Hohokam-to the north who occupied the present-day states of Arizona and New Mexico.

Some archaeologists feel that Paquimé originally began with a Mogollon-like nucleus of people who capitalized on Hohokam precedents for its early community architecture and water control. In the early stages of its development, Paquimé consisted of groups of shallow pithouses which were arranged around a larger community house. Like other Indian cultures at this time (1,500 years ago), they were raising corn, beans, and squash. They supplemented these agricultural foods by hunting wild game and collecting wild plants. They manufactured simple brown pottery.

In the next stage of its development, Paquimé seems to have been influenced by the Hohokam in Arizona. They began to build rectangular surface houses with walls of tightly spaced vertical posts which were plastered with clay. The roofs were constructed of timbers which were covered with brush and grass and then plastered with clay.

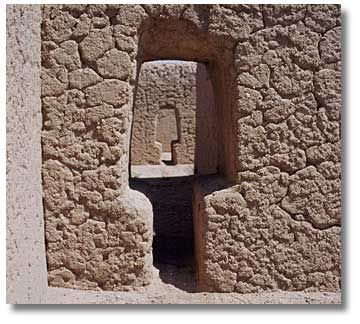

Then the town blossomed after an Anasazi infusion of immigrants. At this time (about 1,000 year ago) they began building single-story adobe-walled room blocks. The characteristics of these room blocks are T-shaped doorways (like those of the Anasazi in Chaco Canyon in New Mexico), raised fire hearths, and stairways.

Even with these northern origins and influences from the Mogollon, Hohokam, and Anasazi, Paquimé was more oriented toward Mesoamerica for trade and cultural customs. About 800 years ago, this influence from Mesoamerica brought about a flourishing of Paquimé. They built ceremonial mounds and ballcourts similar to the Mesoamerican cities to the south.

The people of Paquimé built adobe houses that were six and seven stories in height. These apartments offered residents an airy living space. Occupants were using heated sleeping platforms, raised platform cooking hearths, and domestic running water. By 1300, the town had a population of about 2,500 people.

At its height, Paquimé covered 88 acres. Its horseshoe-shaped apartment complex overlooked public areas to the west, south, and north. The apartment complex included a public plaza as well as private courtyards. In addition to living quarters and domestic storage, the complex also had a subterranean well, a sweat bath, nesting boxes for turkeys and macaws, artisan work areas, and ceremonial rooms.

In addition to raising crops in irrigated fields, the people of Paquimé bred and raised turkeys as well as macaws. The scarlet and soldier macaws were highly valued for ceremony, display, and trade.

The public areas at Paquimé included an open market, effigy mounds, ceremonial mounds, and ballcourts. Unlike the Anasazi pueblos to the north, there were no kivas (underground ceremonial chambers).

One of the effigy mounds was shaped like a snake and may have been a symbol of the Mesoamerican deity Quetzalcoatl. Quetzalcoatl was identified with the planet Venus, wind, war, and human sacrifice. The symbol of Quetzalcoatl-a serpent with a feathered plume-was found frequently in the monuments, jewelry, ceramics, and rock art.

Images of another Mesoamerican deity, Tlaloc, were also found at Paquimé. Tlaloc was associated with storms and water, and priests at Paquimé may have sacrificed children to Tlaloc at springs and ponds.

Another effigy mound is shaped like a bird (perhaps a beheaded turkey). There is also a mound structure shaped like a cross which is aligned with the cardinal directions and helps mark the passage of the seasons. One of the truncated pyramidal mounds served as a signal platform and another was used for elite burials and ritual celebrations.

One of the city’s two ballcourts was T-shaped and was attached to one of the most elaborate sections of the apartment complex. This area served as the setting for some of Paquimé’s most important religious ceremonies. Within the area marked by the walls of this ballcourt, the priests re-enacted mythical games.

The town of Paquimé was a major trading center and through this center luxury goods such as shells, copper, macaws, and pottery made their way into Arizona and New Mexico from Mesoamerica. The people of Paquimé were known for making copper bells and ornaments. Artisans used shells imported from the Gulf of California to craft necklaces, pendants, bracelets, rings, and musical instruments. Using quartz crystal pestles, chipped stone gravers, and stone abraders, the artisans produced beads from Olividae and Conidae shells, as well as cut and incised pendants. These items were used in religious rituals and were exported to distant trading partners.

Paquimé potters produced both effigies and painted vessels which showed men, women, macaws, owls, snakes, badgers, fish, lizards, and mountain sheep. The images were detailed enough so that modern scientists can identify the actual animal species.

Itinerant traders connected the community with both the Mesoamerican civilizations to the south and to the North American Southwestern Pueblos to the north. Some archaeologists refer to the trading network as the “Aztlan Mercantile System.” The trading network linked the civilizations in the Valley of Mexico with northern Mexican and the Southwestern United States. The stock in trade for these itinerant traders included fabric, smoking pipes, tobacco, metal objects, turquoise, cacao, and ceramics. They also transported macaws from the rainforests of Central America, across the deserts of northern Mexico, to Paquimé. Somehow, they managed to keep the birds alive during the trip.

Paquimé was destroyed about 1450 by an enemy people who burned the city and killed several hundred men, women, and children. The bodies of the dead were left where they fell. In addition, the precious breeding macaws and turkeys were left in their pens to die of neglect.

Leave a Reply