The Potlatch

( – promoted by navajo)

One of the cultural features of the Northwest Coast First Nations’ cultures is the potlatch. The Europeans, and particularly the Christian missionaries, opposed the potlatch and it was banned in both Canada and the United States. However, Indian people continued the potlatch away from the government and the missionaries.

The word “potlatch” is the English version of the Nootkan word “p’alshit’” which means “to give.” Material wealth is important among the Indian nations of this area, but by giving things away at the potlatch, families and individuals gain status. The potlatch functioned as a means for passing around among the members the surplus wealth of the society; the only thing that changed was the status of the individuals. Some people feel that the potlatch was the functional equivalent of taxation in modern society. Vast amounts of goods and wealth were distributed through the potlatch.

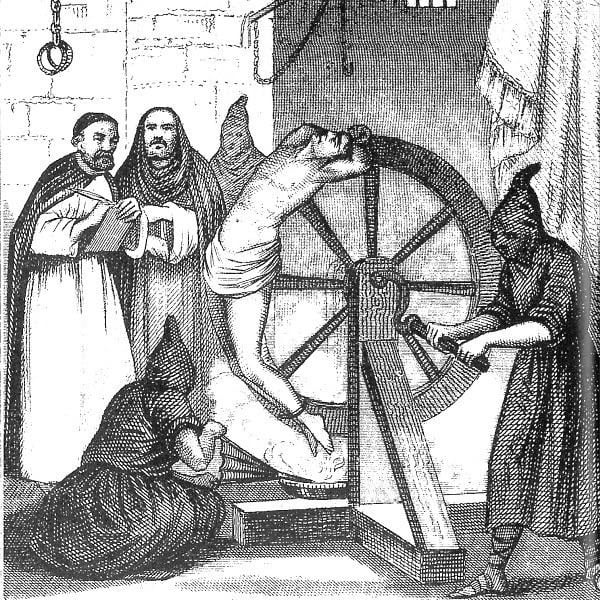

The traditional potlatch was basically a ceremony: a series of songs, dances, and rituals. At the same time, it was an expression of social stratification. The Christian missionaries opposed it only in part because it was an expression of non-Christian aboriginal religion: the primary opposition to it came from the fact that it involved giving away wealth. This was a concept which seemed detrimental to many Europeans whose cultures equated the acquisition of personal wealth with success.

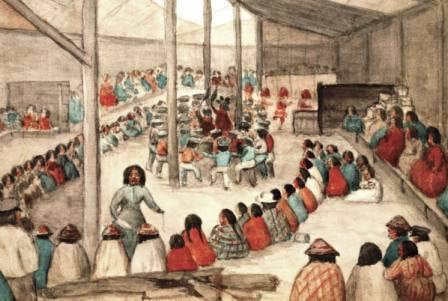

In the potlatch, a high ranking person and his family gives away wealth and in this way they reassert their high rank. Traditionally, the lavish giving of presents was held in winter when all the food had been gathered in. The gift-giving was accompanied by songs, dances, and drama dealing with the grandeur of the host’s family and ancestry.

Traditionally, only a chief could hold a potlatch. During the potlatch, the chief’s privileges-names, songs, stories, and dances “owned” by him-would be recited. The guests would tacitly confirm the social relationships and history which was told.

Potlatches were traditionally held to mark births, naming, puberty, weddings, and deaths. For a potlatch, the family would amass wealth and then give it away to all who came to witness the rite of passage. Without the validation of a potlatch the privileges of a change in social status were considered to be unearned and therefore could not be exercised. All of the names, ranks, privileges, and honors of the family inheritance were meaningless without the formal ritual of hospitality and the acceptance of gifts by the guests.

The guests at a potlatch saw and experienced the social business of the event, such as the inheritance of a name. They mentally recorded and validated that which had happened. In addition, the food dserved at the potlatch came from all of the territories of the house and by consuming this food the guests acknowledged the house’s right to these lands and resources. The potlatch was a public statement of a person’s rank and importance; by accepting the gifts, the guests acknowledged the rights of the host.

The preparation for a chief’s potlatch would take several years. Each person in the tribe would make contributions based on their rank and each contribution was publicly announced. The chief, having the highest rank, would contribute the most, followed by his nephews who were in line to inherit his title. In non-chiefly potlatches, the chief would not contribute.

The potlatch itself often lasted for days with special songs for greeting the arriving guests and the serving of large quantities of food. During the several days of the potlatch, the hosts provided the guests with two large meals per day.

The goods given away at a potlatch include money, canoes, flour, kettles, dishes, Hudson’s Bay blankets, sewing machines, tables, slaves, and coppers. Gifts were distributed according to rank. Everyone who attended the potlatch was given something, but commoners received only tokens. The chiefs and nobles would receive the most, and traditionally, the chiefs upon returning home would distribute what they had received to the members of their house, town, and tribe.

The potlatch was attacked by Canadian authorities as being wasteful and destructive of moral and economic initiative. The Canadian government felt that it stood in the way of development and modernization. In 1883, the Superintendent General of Indian Affairs John A. Macdonald defined the potlatch as

“the useless and degrading custom in vogue among the Indians … at which an immense amount of personal property is squandered in gifts by one Band to another, and at which much valuable time is lost.”

In 1884, the Canadian government formally outlawed the potlatch. From a Native perspective, this meant that they could not celebrate the birth or naming of their children as required by traditional law, nor could they end their mourning after death.

The following year, the Canadian government amended the law against the potlatch to outlaw Native participation in the ceremony. The law stated:

“Every Indian or other person who engages in or assists in celebrating the Indian festival known as the ‘Potlatch’ or in the Indian dance known as the “tamanawas” is guilty of a misdemenour, and shall be liable to imprisonment.”

The missionaries stressed that the potlatch was a “degrading practice” which was a barrier to the “civilizing” of the Indians.

In spite of the potlatch ban, in 1886 Tsimshian chief Ligeex hosted a potlatch in British Columbia. The goods to be given away were hidden behind a partition in the house. The pile of goods was so high that the roof boards were removed to accommodate it.

In 1918, Duncan Campbell Scott, Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, sent a circular to all Indian agents in British Columbia telling them that the war in Europe had put extreme pressures on the economy and therefore no wasteful practices could be allowed. Gift-giving at potlatches is wasteful, in Scott’s view, and therefore the agents were to use their powers to convict all who participated in a potlatch.

In 1919, four potlatchers were arrested at the Kwawkewlth Agency in British Columbia. When the four and seventy-three additional community members signed an agreement to obey the law and stopped the practice of the potlatch, the Crown dropped its charges. The following year, eight Indians from Alert Bay pled guilty to participating in a potlatch. Seven were sentenced to two months in jail. The eighth, an elderly man, received a suspended sentence.

In 1921, Nimpkish (Kwakwaka’wakw) chief Daniel Cranmer sponsored a potlatch-reported to be the largest ever given up to that time-in order to repay his wife’s family as part of the marriage settlement. The local Indian agent decided to prosecute those who participated in the ceremony and was able to obtain 45 convictions. Twenty-three people, including ranking chiefs and women, were sent to prison. Twenty-two received suspended sentences in return for agreeing to hand over their potlatch regalia. As a result, 750 ceremonial objects were turned over to the government. To be charged with crimes as speaking, dancing, and giving or receiving gifts appeared to the Kwakwaka’waka to be an utter contravention of natural law.

With regard to the confiscated potlatch ceremonial items, the local Indian agent put them on display in the parish hall at Alert Bay and charged an admission. The items were then sold to collectors and museums. Some of the items were shipped to the National Museum in Ottawa and some were sold to a collector for the Museum of the American Indian in New York.

Potlatching declined as a result of this persecution. The potlatch was pushed underground after the Cranmer convictions. People continued to potlatch, but they either held them in remote villages away from government eyes or they disguised the potlatch as a Christmas or wedding exchange.

In 1951, the Canadian Indian Act was modified and the laws against the potlatch were dropped. While the potlatch had continued in spite of the law, it now took on a new vigor.