Moor’s Indian Charity School

( – promoted by navajo)

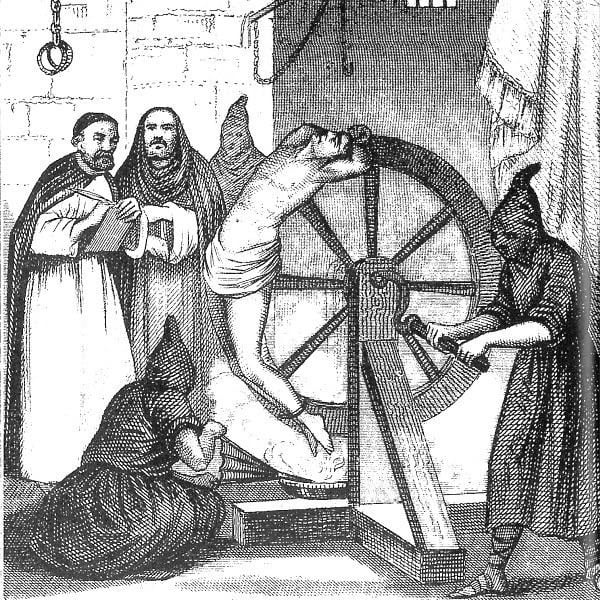

Many Christian missionaries, both Protestant and Catholic, have wrestled with the problem of how best to convert the “pagan” Indians. In 1754, Eleazar Wheelock felt that Indian missionaries could be supported for about half the cost of English missionaries; they spoke the Indian language; and they were accustomed to Indian lifestyles. Wheelock wrote:

“Indian missionaries may be supposed better to understand the tempers and customs of Indians, and more readily conform to them in a thousand things than the English can; and in things wherein the nonconformity of the English may cause disgust, and be construed as the fruit of pride, and an evidence and expression of their scorn and disrespect.”

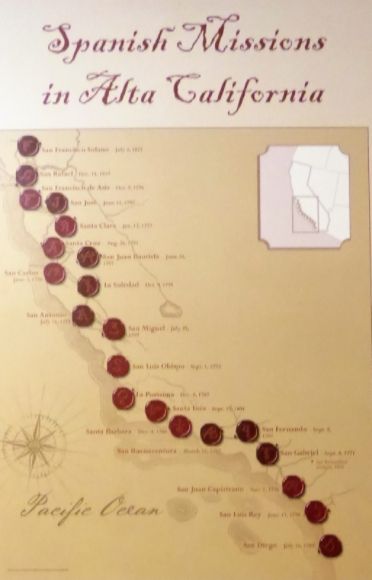

In order to create the Indian missionaries needed for this effort, Eleazar Wheelock founded Moor’s Indian Charity School in Lebanon, Connecticut. The school was named for its chief benefactor, Joshua Moor, who donated a house and two acres of land.

While some of the inspiration for the school had come from Wheelock’s experience in tutoring a Mohegan named Samson Occom from 1743 to 1748, Wheelock felt that the plan for the school was divinely inspired.

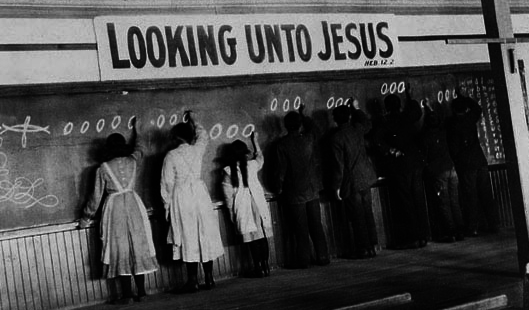

The Indian boys who attended the school were separated from their own culture and were given a classical education in Latin and Greek. Looking at the school through the lens of British standards, it appeared to be a sound approach to education. From an Indian viewpoint, however, it was a form of cultural genocide.

The Indian boys began each day with prayer and catechism before dawn. This was followed by formal instruction in Greek and Latin. The Indian boys were required to work on the school’s farm half of the day-a task classified as “husbandry”. Most of the Indian students showed little interest in farm chores.

Indian girls attended academic classes only one day a week. The rest of the time they were delegated to non-Indian households where they worked as servants (some would say that they are slaves). Like other females in British New England, they were taught subjects that would assist their husbands’ needs. Wheelock, like other missionaries, educators, and English leaders of this era, was convinced that the presence of Indian girls at the school would result in future wifely companionship for the Indian missionary husbands.

Initially, recruitment of students was limited to New England and New Jersey since the war between the French and the English (sometimes called the French and Indian War, 1754-1763) interfered with recruitment in other areas. Two Delaware boys, John Pumshire and Jacob Woolley, were the first two students at the school. They were later joined by Pequot, Mohegan, and Montauk students.

Beginning in 1761, Wheelock was able to recruit students from the Iroquois in New York. At the same time, the first two Indian girls enrolled: Amy Johnson, a Mohegan and Miriam Storrs, a Delaware.

Probably the most famous student at Moor’s Indian Charity School was the Mohawk Joseph Brant. In 1761, three young Mohawk men-Joseph Brant, Negyes, and Center-were sent to the school. All of the Mohawk kept their horses ready so that they could flee back to their own country. Center and Negyes soon returned home, but Brant stayed on to improve his written Mohawk and to learn spoken and written English.

Joseph Brant, whose Mohawk name was Thayendenegea, was the son of Aroghyiadecker (Nickus Brant), the grandson of Sagayeenquarashtow (one of the sachems who visited Queen Anne’s court at the beginning of the century), and the brother of Molly Brant, the consort of Sir William Johnson, the British Indian superintendent.

Students from the school sometimes helped in missionary efforts. For example, in 1761, David Fowler (Montauk), who was a student at Moor’s Indian Charity School, accompanied his brother-in-law, the Mohegan Christian missionary Samson Occom on a visit to the Oneida. They visited the Oneida on behalf of the Presbyterian missionary organization, the Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge. The Oneida were receptive to a missionary and a school and they presented Occom with a wampum belt to bind them together in love and friendship. Occom told the Oneida that they were to wear their hair long, in the English style, and that they were not to wear Indian ornaments.

In 1765, the first students from Moor’s Indian Charity School were ready for examination by the Connecticut Board of Correspondents, one of several such colonial boards that represented the Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge. A total of eleven students graduated, with three Indian boys becoming schoolmasters to the Iroquois and six serving as teaching assistants.

In 1768, Moor’s Indian Charity School closed. About 50 Indian students had studied at the school and 15 had returned to their homes as missionaries, schoolmasters, or assistants to non-Indian ministers. Overall, Moor’s Charity School made no lasting evangelistic mark.

By the mid 1760s, Eleazar Wheelock had realized that his plan of sending missionaries to the Indian homelands to educate and convert Indians was not working as planned. He began to look for new directions in which to move. In 1769, he received a charter for a new school, one which would be named for William, second Earl of Dartmouth. Wheelock was appointed Dartmouth College’s first president.