( – promoted by navajo)

In 1921, Albert Fall, the former Senator from New Mexico, was appointed Secretary of the Interior by President Warren Harding. Since the Indian Office (now called the Bureau of Indian Affairs) is a part of the Department of Interior, this meant that Fall was now in charge of Indian affairs. He was openly hostile to Indian rights, particularly religious rights. One of Fall’s first acts was to enforce the prohibition against the Plains Indian Sun Dance. Those who participated were to be jailed for 30 days in the agency prison.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs issued a lengthy list of Indian offenses for which corrective penalties were provided. One concern was the reckless giving away of property and another concern was Indian dances which were described by the Bureau as a “ribald system of debauchery”. The official attitude toward Indian dances can be seen in a report by the superintendent of the Fort Peck Reservation in Montana:

“The dance itself is extremely demoralizing because when they dance they insist upon giving away property. More than one-half of these Indians if allowed to would give away all of their property. The Indian dance has a direct influence against the Church influence.”

A year before Fall was appointed Secretary of the Interior, the peyote religion (Native American Church) had been carried to the Shoshone and Bannock of the Fort Hall Reservation in Idaho by Shoshone spiritual leader Jack Edmo and by Sioux spiritual leader Cactus Pete. Jack Edmo first encountered peyote at the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota during his summer travels. He soon began leading regular Saturday night peyote meetings. The new religion rapidly spread across the reservation and alarmed agency officials. The Indian agent arrested Jack Edmo and others as he viewed peyote meetings as a form of immorality. He then contacted the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to see if he was authorized to try them for violating Indian Office Regulations against the practices of medicine men. With Fall guiding Indian policies, the Indian agent for the Fort Hall Reservation was informed by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs that the use of peyote and peyote meetings were in violation of Indian Office Regulations. He therefore posted a notice informing the Shoshone and Bannock that the introduction, use, or possession of peyote was illegal.

Circular 1665 from Commissioner of Indian Affairs Charles Burke, issued in 1922, recommended that people be educated against Indian dances and that government employees work closely with the missionaries in matters which affect the moral welfare of the Indians. Like many non-Indians during this era, Burke regarded Indian religions as superstitious and backward. While the Indian Service could not impose Christianity upon the Indians, Burke believed it should do everything in its power to assist the religious volunteers who worked among the Indians.

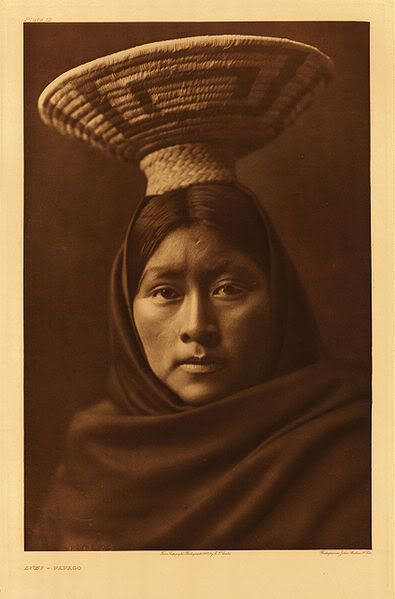

The Tohono O’Odham on Arizona’s Papago Reservation held traditional Náwai’t ceremonies in 1922 in order to break an extended drought. The Náwai’t includes the ritual consumption of tiswin, an alcoholic beverage made from the fruit of the giant Saguaro Cactus. The consumption of tiswin results in vomiting, a recognized ceremonial feature which is called “throwing up the clouds.” The Bureau of Indian Affairs had the agency police raid the villages of Big Fields and Santa Rosa where several hundred participants were dispersed. The police arrested several leaders and Keepers of the Smoke for making tiswin. While the Bureau of Indian Affairs continued to warn people about this ceremony, the Tohono O’Odham continued to hold the ceremony in secret.

Word of the efforts of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) to prohibit Pueblo religions in New Mexico reached the Hopi in 1922. Several Hopi leaders decided to meet in Winslow, a non-Indian town which was located off of the reservation. They feared that if they were to meet on the reservation that the BIA would arrest them. Meeting with the Hopi was the distinguished writer James Willard Schulz. Schulz heard the Hopi complain about threats from government if they continued their religion. One elder stated that he would rather be shot down by the government while doing his religion than try to live without it.

In 1923 the Commissioner of Indian Affairs updated the list of Indian offenses-activities for which Indians could punished. The Commissioner suggested that maypole dances be used as a substitute for traditional Indian dances at Indian schools. He was apparently unaware that the maypole dances were survivals of European pagan fertility dances around phallic icons.

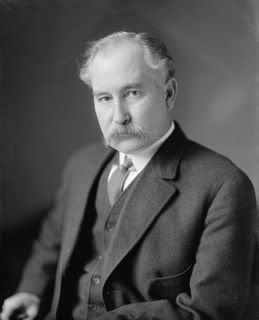

In response to the suppression of Indian religions and cultures under the Albert Fall administration, the American Indian Defense Association was formed to lobby Congress for greater cultural and religious freedom for Indians. It was composed primarily of middle to upper class non-Indians. John Collier was selected as the organization’s executive secretary.

In 1920, Mabel Dodge had taken social worker John Collier to watch the Red Deer Dance at Taos Pueblo in New Mexico. Collier was astonished at what he saw. This was a life-changing experience for him. He would later write:

“I was rocked; it was like a hallucination or earthquake; a sudden dread-fear; the time-horizon pushed back in a moment and enormously… That solitary experience of ‘cosmic consciousness’ had been mine, that forever solitary translation.”

Collier would later become the Commissioner of Indian Affairs and under his administration there would be great religious freedom for American Indians.

In 1923 Albert Fall left office and would later be jailed for his role in the Teapot Dome scandal. The active suppression of Native American religious ceremonies, however, would continue for another decade, ending with the election of Franklin Roosevelt as President.

Leave a Reply