( – promoted by navajo)

Like people throughout the world, traditional Native American cultures recognized and celebrated the changes that people experience as they age. Human infants are often greeted with certain celebrations, ceremonies and rituals in the minutes, days, or months following birth. As the infant grows into childhood and then into adulthood and then into old-age, each of these transitions may be marked by more celebrations, rituals, and ceremonies. And finally, there comes death.

Wellbriety Background:

Wellbriety is a concept which grew out of attempts to bring sobriety to American Indian alcoholics and drug addicts. In order to bring about long-term sobriety, long-term changes in addictive behaviors, the entire community needs to embrace wellness-to obtain wellbriety. Wellbriety is a community approach which incorporates traditional Native American world views.

Wellbriety views the Medicine Wheel as a circle of teaching that explains that anything growing is a system of circles and cycles.

One of these is the cycle of seasons: spring, summer, fall, and winter. Another is the cycle of life: baby, youth, adult, elder. On a personal level, the four directions of human growth are emotional, mental, physical, and spiritual.

The Cycle of Life:

As with the cycle of the seasons, traditional cultures recognize and celebrate lifecycles with ceremonies.

Many Native American cultures have ceremonies which mark the arrival of a new baby. Among the Chiricahua Apache, the Cradle Ceremony is conducted four days after birth. The significance of this brief rite is to spare the child from evil influences so that it would occupy the cradle in the future. The ceremony involves marking the child with pollen, presenting the cradleboard to the four directions, and then placing the child in the cradleboard.

In English, the word “infant” means “unable to speak” in Latin [in (not) + fari (speak)]. In many American Indian cultures, a child is considered to be human when it can speak. This marks the transition from baby to youth. In many Indian cultures, this transition is marked with a naming ceremony in which the child, now considered fully human, is given a new name, one which reflects the child’s human characteristics.

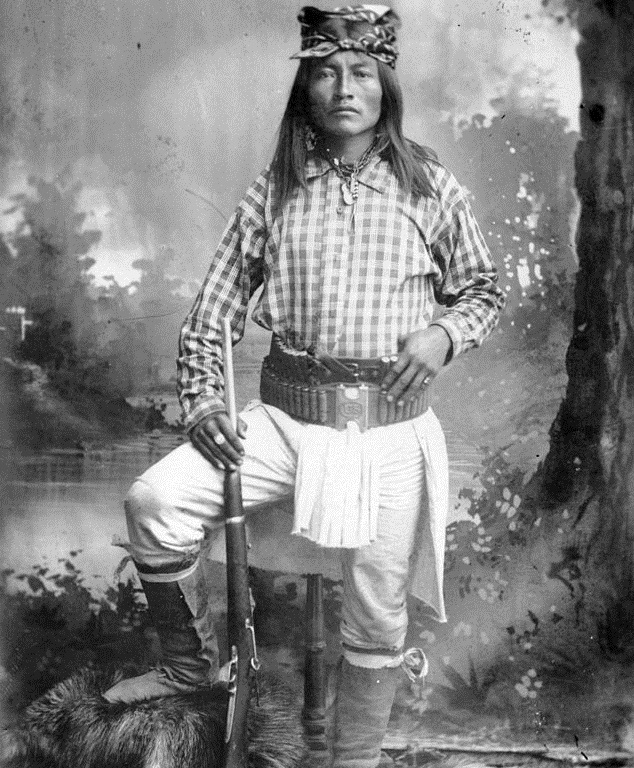

In many American Indian cultures, there would be a ceremony to mark the transition from youth to adult. In some of the cultures, particularly on the Great Plains and in the Columbia Plateau region, this would include a formal vision quest in which the youth would obtain a spiritual mentor, or tutelary spirit.

Among the Ojibwa, children would start fasting for visions at age four or five. At first they would go into the woods and spend a day without food or water while waiting for their visions. Later, they would spend four or more days at time fasting and waiting for their visions to come to them. Both boys and girls sought visions.

For the first vision quest among Ojibwa children, the face and arms are blackened with ash and then the child is taken to the Place of Visions. This is usually a location which is felt to be unnatural, a place formed by neither humans nor nature. On the occasion of the vision quest the spirits would welcome human visitors to this place. After making an offering of tobacco and asking the spirits to bring a vision to the child, the parent leaves. For a number of days the child waits alone, waiting for a vision.

The vision often comes in the form of a particular animal who gives special instructions on how to live, teaches special songs, and shows how to use special medicines. This animal or guardian spirit becomes the person’s personal Manitou. Often the person then carries a representation of this spirit which represents the essences of the spiritual power. Throughout one’s life one can call upon the guardian spirit for assistance, guidance and protection by using a representation.

Among the Western Apache there is a girl’s puberty ceremony which invests in young girls the qualities which are felt to be important for adulthood. This is an elaborate ceremony which has consequences for the entire community. In the ceremony, the power of Changing Woman enters the girl’s body and lives there for the four days of the ceremony. The gift of Changing Woman is longevity and physical health.

Among the Kwakwaka’wakw on the Northwest Coast, the girl’s puberty ceremony, called the Ixanttsila, was a pivotal moment in a girl’s life, marking her transition into womanhood. In preparation for the ceremony, the girl would be secluded for 16 days. During this time she would be taught how to conduct herself.

The transition from adult to elder is more subtle. Among many Indian groups, this is seen by the use of titles such as “uncle,” “aunt,” “grandfather,” and “grandmother.” These titles do not indicate genetic relationships, but rather they show a respected status. It is to these elders that the youth and the adults turn for the teachings about the culture, its history and its meaning.

Leave a Reply