Marriage between Indians and Non-Indians

( – promoted by navajo)

In 1808, President Thomas Jefferson told an Indian delegation who was visiting Washington:

“You will unite yourselves with us and we shall all be Americans. You will mix with us by marriage. Your blood will run in our veins and will spread with us over this great Island.”

We don’t know what response the Indians had to Jefferson’s words, but many non-Indians tended to be less than enthusiastic about marriage with Indians and about the children which might result from these unions. While the large fur trading companies at this time-Hudson’s Bay Company and the North West Company-encouraged their traders to marry Indian women as a way of gaining trading partners, there was strong opposition to the idea of Indian men marrying non-Indian women.

Jesuit missionary Lawrence Palladino, writing in 1893, stated:

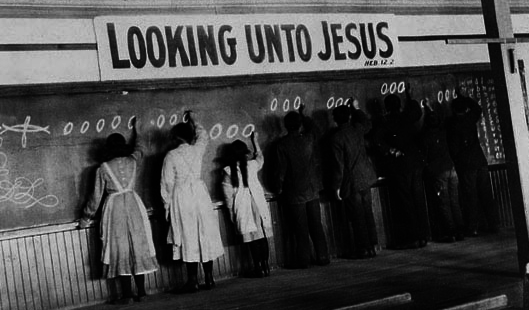

“Experience has amply proven that the Indian cannot be civilized except on Christian principles, through Christian methods, in Christian schools, by Christian teachers.”

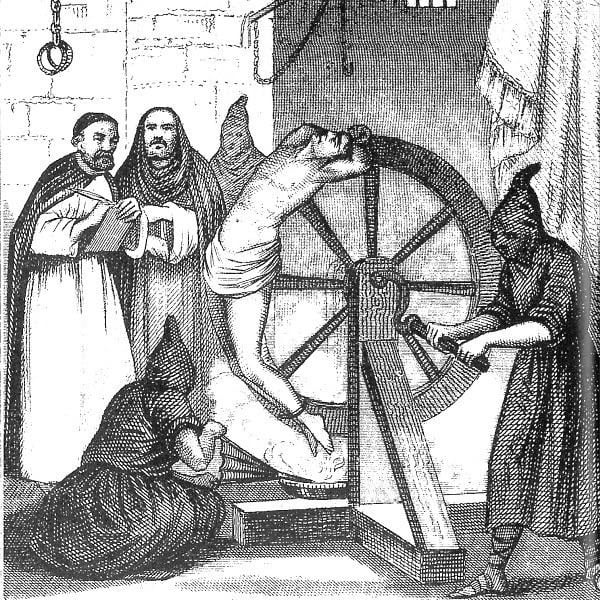

Christian missionaries, both Protestant and Catholic, in their attempts to convert Indians, ranted against Indian forms of marriage such as polygyny (the marriage of a man to more than one women), the sexual freedom of Indian women, and the ease of Indian divorce. They preached that Indians needed to be married in the Christian fashion. While the missionaries were attempting drag Indians into “civilization,” they did not view the Indians as equals and they discouraged marriage between Indians and non-Indians.

In 1816 the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions declared that it proposed for the Cherokee-

“To make the whole tribe English in their language, civilized in their habits, and Christian in their religion.”

In 1817, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions established the Foreign Mission School at Cornwall, Connecticut to provide an education for young men from “heathen” nations. The following year, two Cherokee men-John Ridge and Elias Boudinot-enrolled in the Foreign Missions boarding school. The two men were cousins who had completed all the education the mission schools in the Cherokee Nation could provide. They hungered for more education, and the missionaries selected them for further training with an eye on making them into missionaries. What the missionaries didn’t envision, however, was love and marriage.

In 1824, John Ridge married a non-Indian, Sarah Bird Northrup. The local newspapers denounced the couple. In the local churches, the marriage was denounced on racial grounds by Christian preachers from their pulpits. Following the marriage ceremony, the couple immediately left the area to avoid being mobbed.

The following year, Harriet Gold, the nineteen-year-old daughter of one of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions’ Foreign Mission School board, asked permission to marry Elias Boudinot. Community residents as well as agents of the school openly and vocally opposed the marriage. The citizens of Cornwall, led by the bride’s brother, rallied to burn the couple in effigy on the village green. Agents for the school voiced their opposition to all such marriages and labeled the couple’s conduct as “criminal.” They complained that such marriages were an affront to community sensibilities and violated guidelines of proper decorum.

Jeremiah Everts, the corresponding secretary for the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions defended the marriage. He wrote:

Can it be pretended, at this age of the world, that a small variance of complexion is to present an insuperable barrier to matrimonial connexions? or that the different tribes of men are to be kept forever and entirely distinct?

In order to prevent such marriages in the future, the school was closed.

The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions was not the only Christian missionary group to be troubled by the marriage between an Indian man and a non-Indian woman. In 1933, in New York City, Ojibwa Christian minister Peter Jones married a non-Indian. The New York press reported:

“It was the first time we ever heard the words ‘man and wife’ sound hatefully.”

Other newspapers called the marriage “improper and revolting.”

During the nineteenth and much of the twentieth centuries many states passed laws which prohibited the marriage between Indians and non-Indians. In 1855, for example, the Washington Territorial Legislature passed the Color Act which declared void all marriages between non-Indians and persons of “more than one-half Indian blood.” The law decreed penalties for any clergyman or territorial official who solemnized such marriages. This law was repealed in 1868. Some of the other states which prohibited marriage with Indians included:

Maine: law enacted in 1821 and repealed in 1883

Massachusetts: law enacted in 1705 and repealed in 1843

Rhode Island: law enacted in 1798 and repealed in 1881

Arizona: law enacted in 1865 and repealed in 1962. The Arizona law actually prohibited anyone of a mixed racial heritage from marrying anyone.

Idaho: law enacted in 1864 and repealed in 1959

Nevada: law enacted in 1861 and repealed in 1959

Oregon: law enacted in 1852 and repealed in 1951

North Carolina: law enacted in 1715 and overturned by the Supreme Court in 1967

Tennessee: law enacted in 1741 and overturned by the Supreme Court in 1967