For more than 10,000 years Indian people have lived adjacent to the Columbia River. In the Columbia Gorge area, hundreds, if not thousands, of archaeological sites provide silent testimony to this long period of human occupation. Rock art, in the form of petroglyphs and pictographs, is found throughout the area. The area along the Columbia River from the present-day city of The Dalles to the confluence of the John Day River with the Columbia River contains one of the largest collections of rock art in North America. Archaeologists James Keyser, Michael Taylor, George Poetschat, and David Kaiser, in their book Visions in the Mist: The Rock Art of Celilo Falls, report:

“More than 100 individual rock art sites have been found and recorded in the area and others are discovered each year. The smallest of these are single images but the largest contain more than 1,000 different motifs.”

The rock art is this area includes both pictographs which are painted on the rock, and petroglyphs which are pecked or carved into the rock. Writing about the Columbia Plateau in North America, Keo Boreson, in his entry on rock in the Handbook of North American Indians, reports:

“These carved and painted images give an intimate glimpse into the lives of people that other archaeological remains do not, a visual memory that goes a step beyond the everyday necessities of food and shelter.”

Archaeologist James Keyser, in his book Indian Rock Art of the Columbia Plateau, writes:

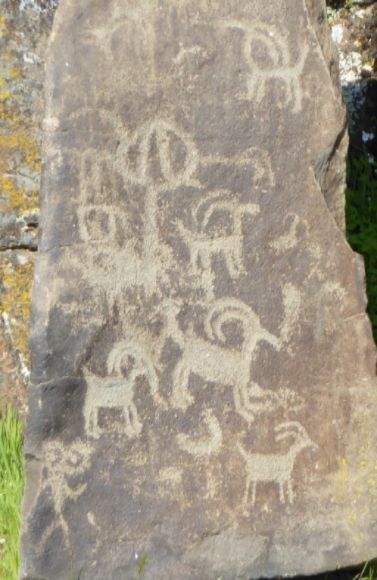

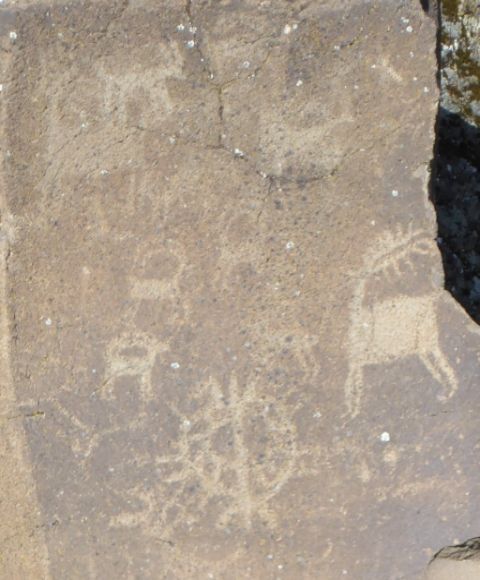

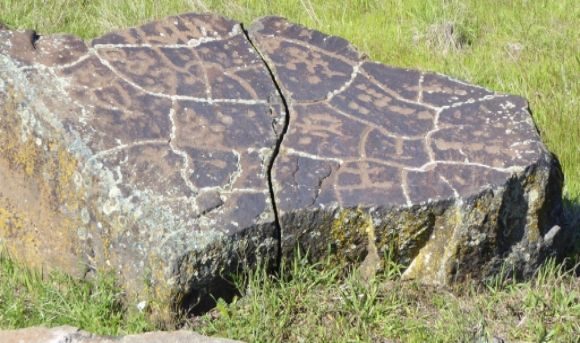

“Petroglyphs are rock engravings, made by a variety of techniques. In the Pacific Northwest, pecking was the most common method: the rock surface was repeatedly struck with a sharp piece of harder stone to produce a shallow pit that was then gradually enlarged to form the design.”

With regard to the location of petroglyphs in the Plateau area, Keo Boreson reports:

“Petroglyphs are frequently found at places near rivers or lakes where people congregated, often where fishing was exceptionally good.”

The area around Celilo Falls was a particularly good fishing area.

The construction of The Dalles Dam on the Columbia River in the 1950s destroyed not only traditional Native American fishing sites and villages, but also important archaeological sites. In 1957, the flood gates on the newly constructed dam were closed and the Columbia River upstream became just another reservoir. Historian Roberta Ulrich, in her book Empty Nets: Indians, Dams, and the Columbia River, describes the scene as the reservoir filled:

“Weeping Indians stood on the shore and watched as the white man’s dam drowned their homes, their livelihood and the center of their culture.”

Archaeologists James Keyser, Michael Taylor, George Poetschat, and David Kaiser describe it this way:

“People gathered to watch as the inundation slowly filled the canyons and sites of ancient villages, radically changing the face of the Columbia Gorge forever. The roaring falls at Celilo, the focus of fishing and a vast trading network for thousands of years, as well as a center of social and mythological importance, gradually fell silent as it too sank beneath the rising tide of water and the needs of modern ways of life.”

Within six hours, Celilo Falls, an important resource and spiritual site, disappeared beneath the rising waters.

James Keyser, Michael Taylor, George Poetschat, and David Kaiser report:

“Although amateur and professional archaeologists scrambled to document some of the rock art before inundation, countless sites were lost to posterity.”

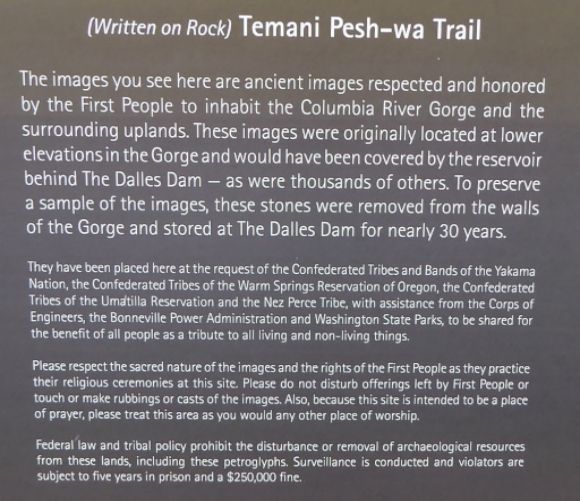

In an attempt to preserve some of this ancient Native American heritage, a number of petroglyphs were removed from their original sites along the river. In 2003, these petroglyphs were placed in their current location in the Horsethief Lake section of Washington’s Columbia Hills State Historical Park.

According to the signs at the Park:

“They have been placed here at the request of the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation of Oregon, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Reservation and the Nez Perce Tribe, with assistance from the Corps of Engineers, the Bonneville Power Administration and Washington State Parks, to be shared for the benefit of all people as a tribute to all living and non-living things.

Please respect the sacred nature of the images and the rights of the First Peoples as they practice their religious ceremonies at this site. Please do not disturb offerings left by First People or touch or make rubbings or casts of the images. Also, because this site is intended to be a place of prayer, please treat this area as you would any other place of worship.”

The petroglyphs are composed of many design motifs. James Keyser, Michael Taylor, George Poetschat, and David Kaiser report:

“The most common Columbia Plateau tradition images across the region are stick figure humans, simple stick figure or black body animals, rayed arcs, rayed circles, dots, tally marks, and a variety of simple geometric designs.”

Shown above is an example of a rayed arc.

Shown above is an example of a rayed arc.  Shown above is a thunderbird motif.

Shown above is a thunderbird motif.  Shown above is an example of a stick-figure human.

Shown above is an example of a stick-figure human.

Shown above are some block animals.

Shown above are some block animals.  Shown above is a Spedis Owl.

Shown above is a Spedis Owl.

A Note About Meaning

Rock art in the Columbia Plateau Culture Area,as in other parts of North America, was not created as a form of aesthetic decoration nor was it art for art’s sake. The rock art was the product of spiritual practices and are a reflection of spiritual, metaphysical experiences and beliefs. James Keyser, Michael Taylor, George Poetschat, and David Kaiser report:

“Columbia Plateau tradition rock art is some of the most homogenous and widespread in North America. Throughout the region a limited suite of characteristic motifs and compositions, done primarily as either red finger paintings or simple pecked petroglyphs, are used repeatedly to represent the contacts shamans and lay people had with the supernatural.”

It is fairly common for non-Indians to speculate about the meaning of American Indian rock art. Some non-Indians view AmericanIndian rock art as a kind of primitive writing and there are even some whoclaim to be able to “read” this writing even though they do not speak an Indian language. In his book The Serpent and the Sacred Fire: Fertility Images inSouthwest Rock Art, Dennis Slifer writes:

“There is consensus among scholars that rock art is not ‘writing’ and cannot be ‘read’ as such. It is language only in the sense that symbols are used to represent things in a nonliteral, symbolic manner.”

Ancient America

Ancient America is a series which explores the Americas prior to the European invasion. More from this series:

Ancient America: Stone Artifacts from the Columbia Plateau (Photo Diary)

Ancient America: The Lower Columbia River Area

Leave a Reply