The Oregon rest stops along the highway that follows the old Oregon Trail have kiosks displaying the history of the trail.

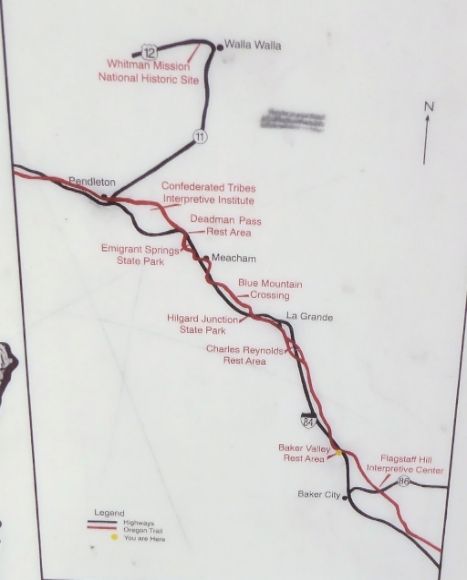

The map shown above shows the rest areas in Eastern Oregon with history displays about the Oregon Trail.

The map shown above shows the rest areas in Eastern Oregon with history displays about the Oregon Trail.

Pathway to the “Garden of the World”

On May 22, 1843, nearly one thousand Americans left Missouri to travel west along the Oregon Trail. The wagon train of about 250 wagons was led by “captain” Peter H. Burnett. People sought to start new lives in an area in which land was plentiful and cheap. There was little consideration for the Native Americans who had lived there for thousands of years.

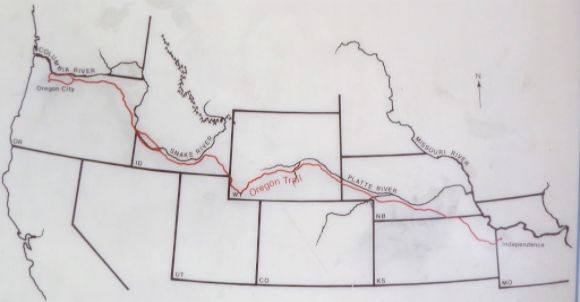

The map above shows the route of the Oregon Trail.

The map above shows the route of the Oregon Trail.

During the two decades following 1843, more than 50,000 emigrants would follow the 2,000 miles of the Oregon Trail from Missouri to Oregon. Publicists billed Oregon as a land of abundance, the Garden of the World. According to the display:

“The fragile landscape’s ability to sustain life eroded as numbers of emigrants increased, and privation, illness and death became constant companions.”

The emigrants denuded the grasslands along the trail. This had an impact on the Native peoples along the Oregon Trail. For example, when the Shoshone returned from their summer buffalo hunt, the found burned-out campfires and filthy campsites which had been left by the Americans.

Powerful Rockey

After an arduous trek, the Oregon Trail emigrants crested the mountains east of the Grande Ronde Valley. With regard to the road, one emigrant called it “the worst possible road, too much for man or beast.” The descent into the valley from Ladd Hill was difficult, usually considered the worst hill of the trip. One 1847 emigrant described it as “a very Steep long hill…and powerful rockey.” The first five miles was steep, crooked, and covered with rocks.

Rough Passage

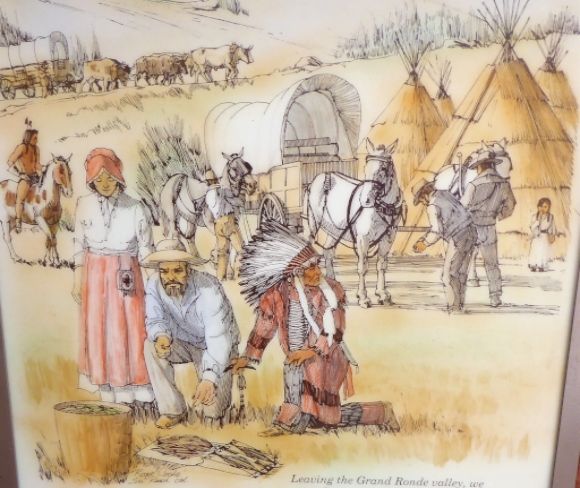

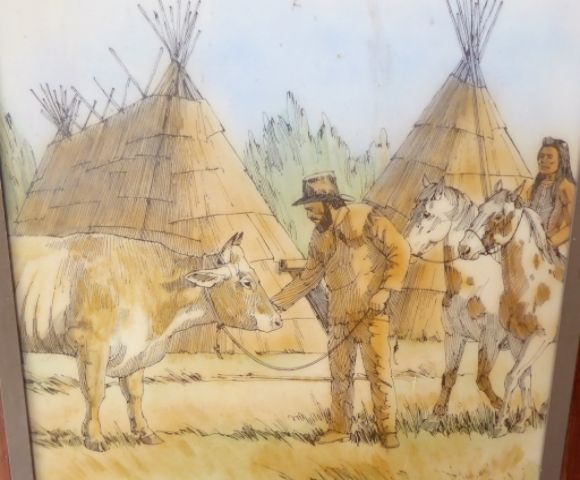

After descending Ladd Hill, the emigrants would often camp at the based of Table Mountain. Here they would rest and trade with Indians.

Notice that in the illustration shown above, the tipis are the hide-covered lodges of the Plains Indians, but rather they are the tule mat-covered lodges of the Plateau Indians.

Notice that in the illustration shown above, the tipis are the hide-covered lodges of the Plains Indians, but rather they are the tule mat-covered lodges of the Plateau Indians.

Enchanted Valley

The Grande Ronde Valley had abundant cottonwood trees and was therefore called Cop Copi by the Indians. In the 1820s, French-Canadian fur traders called in Grande Ronde in reference to its shape (a great circle). To the American emigrants traveling on the Oregon Trail, it was an enchanted valley filled with beauty.

According to one emigrant in 1848:

“It is really one of the loveliest places in the whole world. Just imagine an enormous arena measuring about fifteen miles wide and twenty-five miles long, entirely surrounded by the most beautiful mountains and watered by two lovely rivers.”

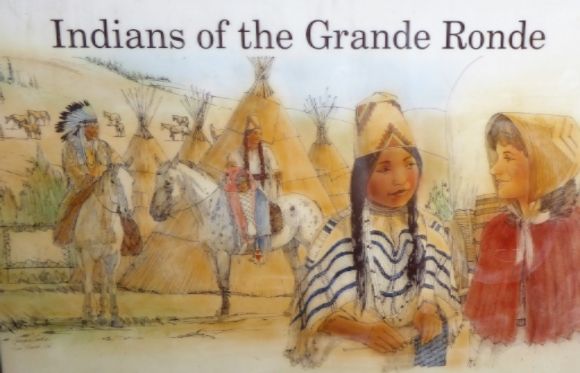

Indians of the Grande Ronde

For thousands of years, American Indian people had lived in and used the resources of the Grande Ronde. As the Americans began arriving in the area, the valley was the domain of the Nez Perce, Cayuse, Walla Walla, and Umatilla nations. Having acquired horses more than a century before, these Indian nations were experienced and skilled horse breeders and had large horse herds.

In 1854, a large intertribal council in Oregon’s Grande Ronde Valley was called by Yakama leader Kamiakin, Walla Walla leader Peopeo Moxmox, and Nez Perce war chief Apash Wyakaikt (Looking Glass). The tribes spent five days listening to Kamiakin’s account of what was happening to the Indian nations west of the Cascade Mountains with the Americans forcing them on to small reservation. Kamiakin urged a confederacy so that the Americans (suyapos) could be fought with a united front. Kamiakin told the council:

“We wish to be left alone in the lands of our forefathers, whose bones lie in the sand hills and along the trails, but a pale-faced stranger has come from a distant land and sends word to us that we must give up our country, as he wants it for the white man. Where can we go? There is no place left”

According to Richard Scheuerman, in his chapter in Indians, Superintendents, and Councils: Northwestern Indian Policy, 1850-1855:

“Reflecting the nature of the traditionally autonomous Plateau tribal groups, the Indian reaction to forming a united front was mixed.”

Spokan leader Garry, Cayuse leader Stickus, and Nez Perce leader Lawyer felt that the Indians were not strong enough to wage war against the Americans. Among the Yakama, Teias and Owhi (both uncles to Kamiakin and Teias is also Kamiakin’s father-in-law) opposed war.

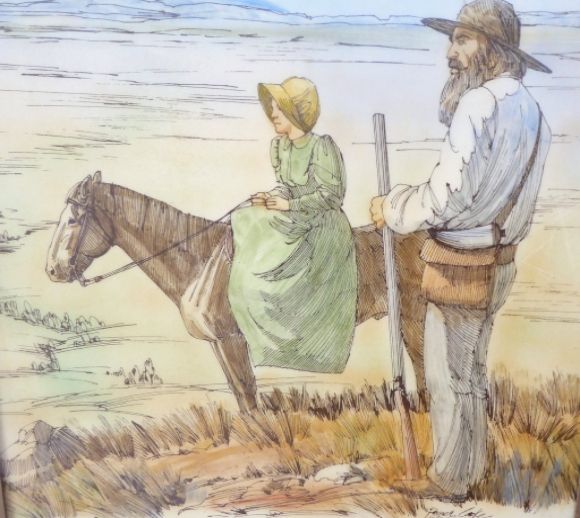

In the illustration above, notice the characteristic Plateau woman’s woven hat.

In the illustration above, notice the characteristic Plateau woman’s woven hat.

Eager to Trade

According to the display:

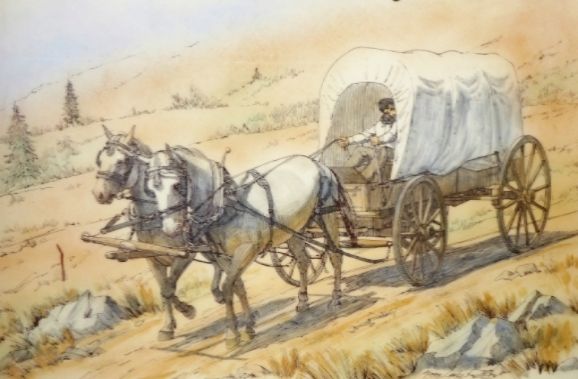

“The trek westward on the Oregon Trail was arduous; wagons broke down, animals died of exhaustion, and supplies were depleted. Although emigrants could re-provision at trading posts along the trail, trade with Indians was vital to survival. The Indians of the Grande Ronde Valley were eager to barter with emigrants.”

With regard to trade with the Indians, the Emigrant’s Guide to Oregon and California, published in 1845, recommended:

“Bring plenty of cheap cotton shirts to trade with the Indians. Also bring blankets, red and blue cloth, butcher knives, fish hooks, flints, lead, powder, beads, rings, mirrors and rice.”

Notice the traditional Plateau longhouse on the left and the mat-covered tipi on the right.

Notice the traditional Plateau longhouse on the left and the mat-covered tipi on the right.

The Indians would often take worn-out livestock in trade, nurture them back to good health, and trade them to later emigrants.

Skinning Post

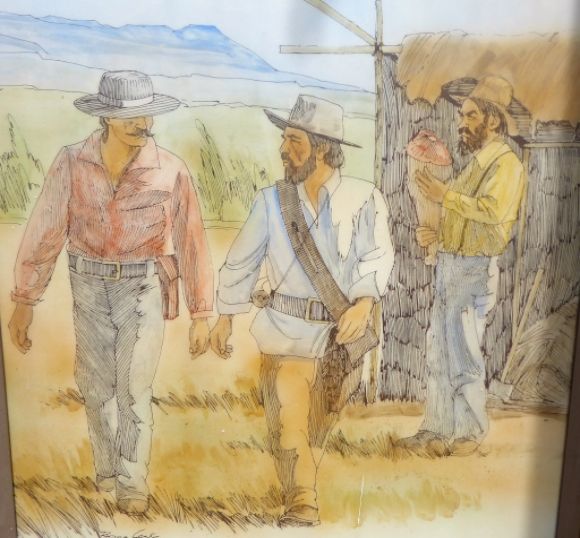

According to the display:

“Most emigrants traded with Indians along the Oregon Trail; they also hired them as guides and often employed their services at dangerous river crossings. During the 1850s entrepreneurs and itinerant traders from the Willamette Valley established themselves along the emigrant route and competed with the Indians. Although emigrants were always wary of Indians, they often considered white speculators dishonest.”

Leave a Reply