By the last quarter of the nineteenth century, most American Indian cultures had dramatically changed, and many Indian tribes ceased to exist. Many Americans, particularly politicians and academicians, were convinced that American Indians were a vanishing race and would be gone by the first part of the twentieth century. With this in mind, some scientists set out to collect data on the disappearing tribes. In what might be considered “salvage ethnography” they set out to systematically study the beliefs and practices of different tribes. Since these ethnographers were not Indians, they required the help of Indian assistants who served as interpreters of both language and culture. Sometimes the ethnographers would credit their Indian assistants for their insights, and in one instance, the ethnographer, Alice Cunningham Fletcher, encouraged her Indian assistant, Francis La Flesche, to become an ethnographer.

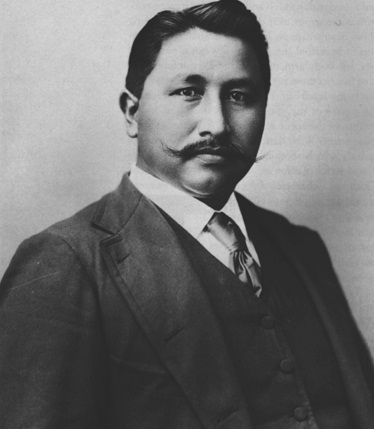

Francis La Flesche was born on the Omaha Reservation in Nebraska in 1857. His father was Omaha chief Joseph La Flesche (Inshtamaza) and his mother was Elizabeth Esau(Tainne), one of his father’s several wives. He was given the name Zhogaxe (Woodworker).

As a child he learned many of the traditional customs of the Omaha and participated in buffalo hunts and ceremonials. His father was Christian, converted by the Presbyterian missionaries, and so Francis also attended the Presbyterian day school on the reservation.

In 1876, the Omaha had their final buffalo hunt, finding a small herd. They brought back very little meat and were forced to live on emergency rations issued by the military at Fort Hayes.

The following year, the American government forced the Ponca to move from their reservation on the Nebraska-Dakota border to Oklahoma. In Oklahoma, the Ponca found that the heat, humidity, and poor soil conditions were unbearable. The Ponca chiefs met with Omaha chief Iron Eyes (Joseph La Flesche) and his daughter Bright Eyes (Susette La Flesche) wrote out a statement from the chiefs which told of their ordeal. She then wrote a telegram to the President.

In 1879 the Ponca under the leadership of Standing Bear left their Oklahoma Reservation to return north. In Nebraska, they were welcomed by the Omaha and given food and shelter. The army, however, tried to force them to return to the reservation, Thomas Tibbles, a newspaper editor stirred up public opinion in their favor. In the court trial that followed, the court found that the Ponca were people and entitled to due process of law. Following their successful trial, Ponca chief Standing Bear, Thomas Tibbles, Susette La Flesche, and Francis La Flesche made a six-month tour of eastern cities. During this time, Francis La Flesche served as an interpreter.

Following what has been generally described as a successful lecture tour, Francis La Flesche was offered a job in the federal agency which would later be known as the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA).

In 1879, Congress had established the Bureau of American Ethnology (BAE) for the purpose of transferring archives, records, and other materials relating to North American Indians from the Interior Department to the Smithsonian Institution. Under the leadership of John Wesley Powell, the BAE expanded its role into ethnographic, archaeological, and linguistic field research. Among the early field ethnographers for the BAE was Alice Cunningham Fletcher.

While working in Washington, D.C. for the BIA, Francis La Flesche began a collaboration with Alice Cunningham Fletcher, an anthropologist and ethnographer. The two first met in 1881 when Alice Fletcher was doing an ethnographic study of Sioux women on the Rosebud Reservation. She was accompanied on her trip to the Rosebud Reservation by Susette La Flesche and Thomas Tibbles and through them became acquainted with Francis La Flesche.

In 1882, the Omaha allotment act became law and allowed the United States to sell that portion of the reservation west of the Sioux City and Nebraska Railroad right-of-way. Under the law, most of the Omaha became private land owners. The Omaha were now under the civil and criminal laws of the state which cannot deny the Indians legal protection. Ethnographer Alice Fletcher was named special agent and arrived at the reservation to allot the lands. She was aided by Omaha interpreter Francis La Flesche.

Alice Fletcher encouraged Francis La Flesche to become a professional anthropologist. Together they produced A Study of Omaha Music (1893) and The Omaha Tribe (1911).

In 1884, Mon’hin Thin Ge, the last keeper of the Omaha tent of war which contains many sacred items, turned the contents of the tent over to ethnologists Alice Fletcher and Francis La Flesche for placement at Harvard University’s Peabody Museum. Fletcher and La Flesche later write:

“The ceremonies connected with these articles had become obsolete owing to the changed conditions brought about by the occupancy by white settlers of the country adjacent to the Omaha reservation; yet the objects were regarded with respect and a sort of superstitious awe.”

In giving the items to the Peabody, he tells Fletcher and La Flesche:

“My sons have chosen a path different from that of their fathers. I had thought to have these articles buried with me; but if you will place them where they will be safe and where my children can look on them when they wish to think of the past and of the way their fathers walked, I give them into your keeping.”

Ethnographers often become very involved with the communities they study, and this involvement goes beyond just collecting data. One example of this can be seen in 1898 when the sacred Omaha White Buffalo Hide was stolen. Ethnographers Alice Fletcher and Francis La Flesche learned the name of the thief and traced the White Buffalo Hide to a man in Chicago who had purchased it. They made an effort to buy it back, but the purchaser refused to sell.

In 1900, Francis La Flesched published his memoir The Middle Five: Indian Schoolboys of the Omaha Tribe, which presents a nostalgic portrait of a student’s experiences at the Presbyterian mission school on the Omaha Reservation. The book did not sell well.

In 1908, he began a collaboration with the American composer Charles Wakefield Cadman. Together they developed an opera in 1912, Da O Ma, which was based on his stories of Omaha life. The opera was never produced.

In 1910, Francis La Flesche joined the BAE where he became the first professional Native American ethnologist. Initially, his job at the BAE involved classifying Omaha and Osage artifacts.

In 1921, his books The Osage Tribe: Rite of the Chiefs and Sayings of Ancient Men were published. His monumental Dictionary of the Osage Language was published shortly before his death in 1932 and War Ceremony and Peace Ceremony of the Osage Chiefs was published posthumously in 1939.

With regard to higher education, Francis La Flesche attended the George Washington University Law school where he earned both an undergraduate degree and a master’s degree.

With regard to his personal life, Francis La Flesche was married to Alice Mitchell in 1877, but she died within a year. In 1879, he married Rosa Bourassa, an Omaha woman. When he moved to Washington, D.C. in 1881, they separated and divorced in 1884. In Washington, D.C., Francis La Flesche shared a house with Alice Fletcher and Jane Gay.

Francis La Flesche died in 1932 and was buried in Nebraska near the graves of Joseph La Flesche, Susette La Flesche, and Rosalie La Flesche. In his short biography of Francis La Flesche in Notable Native Americans, John Little sums up his life this way:

“Francis La Flesche was one of the first Native Americans to have a noteworthy career as a research scholar and writer of scholarly books. This achievement was all the more remarkable in view of the fact that he had only a few years of primary and secondary education at an Indian mission school, followed many years later by academic training in law while working as a clerk for the federal government in Washington, D.C.”

With regard to his ethnographic work, John Little writes:

“He was particularly skilled at persuading elderly tribal leaders of the Omaha to reveal the words and ceremonies of the ancient tribal rituals, which were rapidly dying out.”

Leave a Reply