While the mainstream art world did not begin to recognize American Indian art as a distinctive art form until the twentieth century, during the late nineteenth century the market for American Indian arts-or more accurately, arts and crafts-began to develop. This market included pottery, weavings, drawings, paintings, and other items. The new market was driven by tourism, trading posts, museums, and wealthy collectors. During this time, American Indian art began to shift from tribal art in which artifacts were produced primarily for tribal members to ethnic art in which artifacts were purchased by non-Indians.

Tourism:

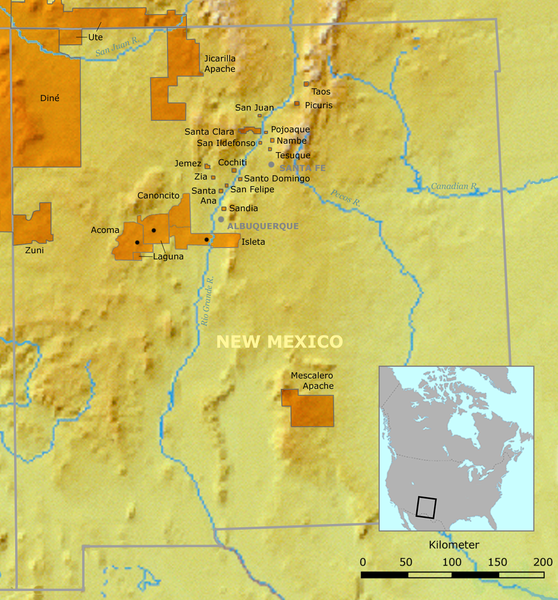

Tourists began to arrive in the Indian Southwest with the railroad in 1881. On the Navajo reservation in Arizona and New Mexico the arrival of the railroad opened up new markets for native crafts, including blankets and silver jewelry. This market, however, was to be largely controlled by non-Indian traders who held federally issued licenses. From the viewpoint of the American government, allowing a free market in Indian arts and crafts would have run counter to the official “civilization” program which was based on the assumption that American Indians were a “dependent” people who were not competent to manage their own affairs.

In 1895, the Santa Fe Railway began a marketing plan to bring tourists into the southwest. One of the primary attractions promoted by the railway was the area’s Indians, particularly the Pueblos.

On the Navajo reservation in Arizona and New Mexico in 1899, the Fred Harvey Company asked traders to have local Navajo silversmiths make souvenirs for railroad tourists. This marked the beginning of commercial Navajo silver jewelry production.

Trading Posts:

In 1881, William Caton, a trader operating at the Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation in South Dakota offered Sans Arc Lakota chief Black Hawk fifty cents in credit at his store for each drawing that he made. Caton promised that he would provide Black Hawk with pencils, ink, and foolscap paper for the drawings. Black Hawk agreed and ultimately provided Caton with 76 drawings.

In 1889, Indian agent C. E. Vandever reported that there were only nine licensed traders on the Navajo reservation in Arizona and New Mexico. He also reported that there were thirty trading posts located just off the reservation. He noted that the

“proximity of trading posts has radically changed their native costumes and modified many of the earlier barbaric traits, and also affords them good markets for their wool, peltry, woven fabrics, and other products.”

At this time, Navajo silversmiths were converting surplus cash (silver coins) into silver jewelry for personal adornment. According to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs:

“When he becomes hard up between harvests, which is by no means uncommon, these ornament are pawned with the traders, but are invariably redeemed.”

By 1890, Navajo weavers were selling about two thirds of the blankets and rugs which they made. They were producing about $25,000 worth of trade goods each year.

The Hubbell Trading Post is shown above.

While blankets and rugs had become economically important to the Navajo, the Indian agent for the Navajo reported that the older women were still making pottery cooking vessels, but the younger women were not. Since pottery and basketry did not have the commercial potential of other Navajo crafts, their manufacture declined and they were replaced by manufactured items.

In 1895, the Rug Period of Navajo Weaving began with the weavers making thicker weavings for sales outside of the reservation. The shift from weaving blankets to weaving rugs comes from the encouragement of the traders who realize that there is a growing market for rugs. Noting the popularity of oriental rugs, the traders display examples of border designs which they encourage the weavers to utilize. At this time, regional styles began to develop. These regional styles were sometimes associated with traders or trading posts in collaboration with the weavers.

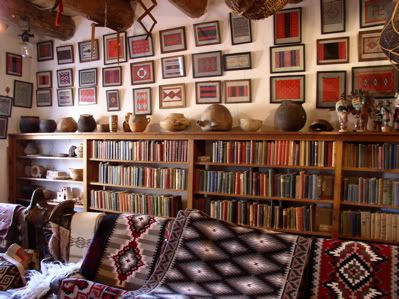

The inside of the Hubbell Trading Post is shown above. Notice the designs for rug borders on the wall.

A Two Grey Hills rug is shown above.

In 1895, Washo basketmaker Dat-so-la-lee brought four willow-covered flasks to Abe Cohen’s Emporium Store in Carson City, Nevada. This began a marketing arrangement that leads to Dat-so-la-lee’s fame as an internationally known basketmaker. Dat-so-la-lee was about 60 years old at this time, and was known for her non-traditional baskets with a spherical shape and a small mouth. She arranged to weave consistently and solely for Abe Cohen in exchange for goods, fuel, clothing, medical care, and a small home. This arrangement was honored by both parties until her death in 1924.

In 1898, Navajo weavers responded to the patriotic fever of the Spanish-American War by making American flag blankets. It is not known if this idea originated with the weavers or the traders.

As the market for Southwestern silver grew, silversmithing diffused to a number of tribes. In 1898, Hopi artist Sikyatala learned silver work from the Zuni artist Lanyade. Sikyatala then taught this to other Hopi. There were regular trading relations between the Hopi and Zuni and so the sharing of silversmithing techniques would not have been strange.

Museums:

The Bureau of Ethnology, a part of the Smithsonian Institution, sent an expedition to the Hopi pueblos in 1882 to survey the villages and to make a collection of material goods. They were instructed to “clean out” the Hopi pueblo of Oraibi, but were threatened by the elders when the purpose of the trip became known. Still, they managed to obtain more than 200 specimens at Oraibi and 1,200 from the three villages of Second Mesa.

When the materials from Hopi arrived at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C., they were often left outside until space could be found to store them. As a result, many items were damaged and these were simply discarded because the museum staff was overwhelmed by the rapid pace of the collecting carried out by the Bureau of Ethnography.

The following year, Dutch anthropologist Herman Ten Kate visited Indian tribes in the Southwest. He accumulated about 500 artifacts which were sent to The Netherlands. King William I had established the Royal Cabinet of Rarities in 1816 and by the end of the nineteenth century, the Dutch, like the Americans, saw their collecting as a salvage operation undertaken to document disappearing cultures.

In 1884, among the Hopi artifacts sent from Thomas V. Keam’s trading post in Arizona to Washington, D.C. were a mummy, a number of sacred masks (described as having been obtained secretly), and a large box of pottery. Keam hoped that the government would purchase the items for the Smithsonian’s National Museum. However, the government declines to purchase the collection and it is eventually obtained by the Peabody Museum at Harvard University.

The archaeological excavations at the site of Sikyatki on the Hopi reservation help to inspire a revitalization of Hopi pottery. Nampeyo, a Tewa woman from the village of Hano, is inspired by the graceful geometry of the ancient designs unearthed at the site and by the dusty mustard and earth terra-cotta colors of the designs. While anthropologist Jesse W. Fewkes claimed to have introduced these ancient designs to Nampeyo, there are many who feel that the revival of Hopi pottery was already underway at this time.

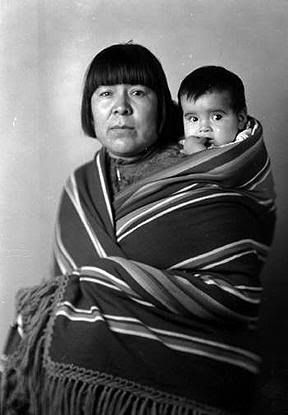

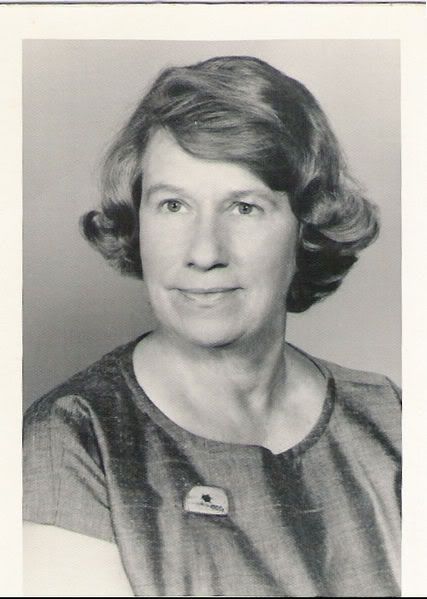

Nampeyo is shown above.

Wealthy Collectors:

In New York City, George G. Heye began collecting Indian art and artifacts in 1897. Like other wealthy collectors at this time, Heye viewed collecting as a way of salvaging or saving what he could from American Indian peoples before their cultures disappeared. He believed that acquiring objects from Indians or from private collections was necessary to reconstruct indigenous cultures and educate future generations. Heye’s collection began with a few articles of Navajo men’s clothing which he acquired while supervising the building of railroad beds along the Arizona-California border. He would later say:

“Naturally when I had the shirt, I wanted a rattle and moccasins.”

Heye’s collection eventually grew to about a million items. In 1989 the collection was transferred to the Smithsonian Institution.

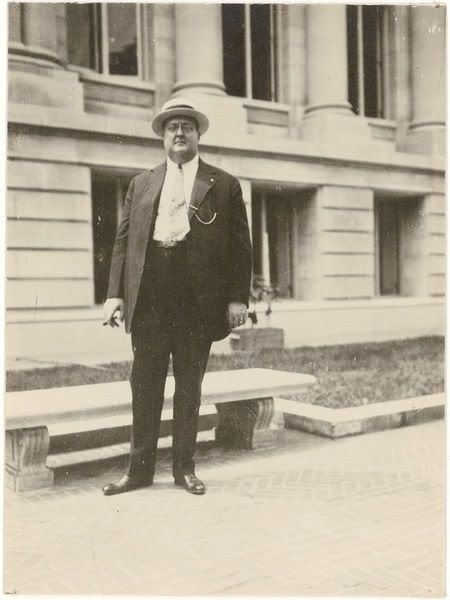

George Gustav Heye is shown above.

Leave a Reply