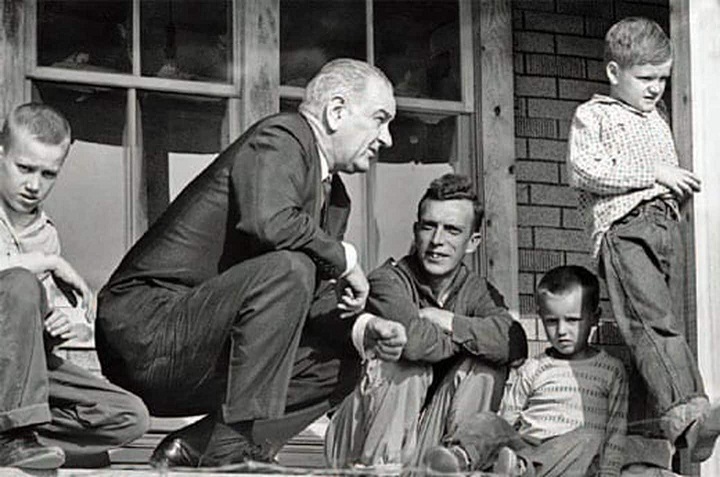

In 1964, with one out of every five Americans living in poverty, President Lyndon Johnson addressed Congress in his State of the Union message and proposed a war on poverty. In response, Congress passed the Economic Opportunity Act which established the Office of Economic Opportunity. While the War on Poverty reduced overall poverty in the United States, it had a great economic, political, and social impact on the country’s Indian nations.

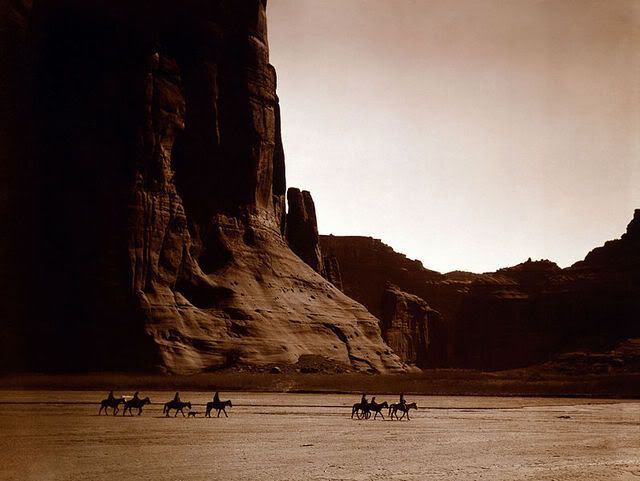

In 1964, the poorest groups in the United States were Indians living on Indian reservations, a fact that had been true throughout the twentieth century and continues to be true today. On the reservations, economic development was controlled-planned, administered, and evaluated-by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). With the creation of the Office of Economic Opportunity, the BIA no longer had a monopoly on the economic future of the tribes. Tribes were eligible for funding for youth programs, community action programs, and other programs. Indian tribes and organizations participated in these programs along with other economically disadvantaged groups. Unlike the earlier BIA programs, these new programs emphasized the need for local involvement at all levels. Soon nearly every tribe in the United States was involved in the War on Poverty and local Indian people, not the BIA, were planning and running the programs. In other words, the War on Poverty provided tribal people with political empowerment.

Through the efforts of the War on Poverty’s community action programs Indians began to understand that they could control their own destinies. While the funding for the Indian War on Poverty was not sufficient to eradicate poverty on the reservations, these efforts resulted in: (1) providing a new generation of Indian leaders with experience in administering government programs; (2) increasing the capacity of tribal governments to administer federal programs, and (3) increasing the desire of Indian people to take over the management of government programs on the reservations.

Community Action Programs:

One of the key components of the War on Poverty was the Community Action Program (CAP). Each CAP was to utilize and mobilize local people to determine how best to deal with poverty in the local community. On the reservations, the CAPs often had bitter relationships with the long-standing BIA administration. The tribal CAPs dedicated the greatest funding to programs such as Head Start, educational development, legal services, health centers, and economic development.

In 1965, the Navajo established the Office of Navajo Economic Opportunity (ONEO) and Peter MacDonald became the new director. ONEO programs soon expanded into many different areas and almost all Navajo living on the reservation were directly impacted by these programs. MacDonald would later go on to become tribal chairman.

In Oklahoma, the Oklahomans for Indian Opportunity (OIO) was formed as a part of the federal government’s War on Poverty program under the initial leadership of LaDonna Harris (Comanche). The OIO amplified Indian voices, not only at the local level, but also at the state and national level.

In Arizona, the Havasupai began a Community Action Program under the Office of Economic Opportunity. They also started a Head Start pre-school program.

Also in Arizona, the Pascua Yaqui Association under the leadership of Anselmo Valencia obtained a grant to start a Community Action Program under the Office of Economic Opportunity. Under this program they trained tribal members to build their own homes and then to purchase them with sweat equity. The new homes were built on a 200-acre parcel which became known as New Pascua.

Rough Rock Demonstration School:

There were many success stories-some large and many small-that came out of the Indian War on Poverty. One of these involved education on the Navajo Reservation. Traditionally, Indian education on reservations had been controlled by non-Indians who had insisted that they knew what was best for Indian children. Ignoring any possibility that parents and tribal parents might have an interest in educating Indian children, these non-Indian educators, usually BIA employees, designed programs with the goal of making Indian children into monolingual English-speaking Christians trained to be laborers.

Since the formation of the Navajo Reservation in the nineteenth century, there had been basically three kinds of schools. First, there were the schools run by the BIA which the Navajo call “Wa’a’shin-doon bi ‘olt’a,” or “Washington’s school.” Then there were the public schools which the Navajo call “Bilaga’ana Yazzie bi ‘olt’a” or “little whiteman’s school.” Finally, there were the mission schools which the Navajo call “Eeneishoodi bi ‘olt’a” or the school of “those who drag their clothes,” a name stemming from the first Catholic priests in long robes who came to the reservation.

What Navajo parents wanted was a school which would give their children an education which both respected and integrated Navajo culture while preparing them for the modern world. With funding from the War on Poverty, the Navajo organized the Rough Rock Demonstration School. This was to be a three year demonstration project. The school was run by the Navajo and became the first wholly Indian-controlled school in the twentieth century.

The Rough Rock Demonstration school is called “Dine’ bi ‘olt’a,” or the “Navaho’s school.” These words express the Navajo pride in the school and this was the only school on the reservation given this designation. It was not that the Navajo people were consulted about this school, but more importantly they were directly and actively involved in its operation.

The educational philosophy that guided the school was based on the idea that the creation of successful programs lies with the community, not education professionals. Policies were established by an elected seven-member, all Navajo school board. Thus the policies and programs were the result of action initiated by the Navajo people. Control of school policy, including handling the budget, was placed in the hands of the Navajo parents, most of whom were without formal education. School board meetings, which often lasted all day, were attended by many community members.

The school taught English as a second language rather than requiring students to know English in order to learn. What would later be known as bilingual/bicultural education began at Rough Rock two years prior to the passage of the Bilingual Education Act which enabled other schools to establish similar programs.

Unlike the earlier BIA schools, both reading and writing in Navajo were taught to all students. Furthermore, the students were encouraged to use the Navajo language in the dormitories, the playground, the dining hall, and in the classroom.

Non-Indian staff members received in-service training to familiarize them with Navajo culture. The school also began programs to teach pottery and basket weaving.

Because the Navajo Nation is large and rural the school operated in part as a boarding school. Unlike the old BIA and mission boarding schools, however, parents from the community worked in the dormitories on a rotating basis. The parents acted as foster parents and as counselors for the students. Community elders visited the dormitories to tell stories and teach the youngsters about Navajo traditions, legends, and history.

In the old boarding schools, students were not allowed to go home during the school year. At Rough Rock, the students were encouraged to go home for weekend visits as often as possible. Transportation was provided to those who needed it. The basic policy of the school was that the children belonged to the parents and not the school.

The Rough Rock Demonstration School clearly demonstrated what is possible when Indian people, with limited or no formal education, were given an opportunity to direct and control their own education system. Rough Rock demonstrated that Indians were ready to exercise leadership in affairs affecting them if they were given the chance.

National Council on Indian Opportunity:

In 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson, noting the success of the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO) projects on Indian reservations, announced:

“I propose a new goal for our Indian programs: A goal that ends the old debate about ‘termination’ of Indian programs and stresses self-determination; a goal that erases old attitudes of paternalism and promotes partnership self-help.”

With Executive Order 11399 President Johnson established the National Council on Indian Opportunity (NCIO).

The following year, the NCIO held a public forum in San Francisco to identify the problems of Indian people and to try to find solutions. At the forum, a number of Indian people spoke out about the problems they faced. These problems included racism, education, poor healthcare programs, unemployment, and housing.

The End:

In 1973, the Office of Economic Opportunity was abolished. However, the effects are still being felt today. With the passage of the Indian Self-Determination Act, government policies turned away from terminating Indian tribes to allowing the tribes to take over government programs. The success of the War on Poverty and the programs run by the CAPs had shown Indian people that Indians could not only run their own programs, but they could develop successful programs as well. The leaders which had been nurtured and trained during the War on Poverty became the new Indian leaders who would guide the people into the twenty-first century.

Leave a Reply