From the very beginning of the European invasion of North America, the newcomers have had an obsession with looting American Indian graves, taking from them not only grave goods, but also parts of human bodies, particularly the skulls. Sometimes these stolen skulls were simply seen as objects of morbid curiosity to be displayed in store windows and back bars, as in the case of Chief Joseph’s skull; at other times they were used as playthings for the college-age children of wealthy families, as in the case of Geronimo’s skull and the Skull and Bones Society; and sometimes collecting human skulls was justified in the name of science and scientific racism. One of the skulls which was stolen in the name of scientific arrogance during the nineteenth century was that of Chinook chief Comcomly.

About Skulls:

The nineteenth century scientific study of skulls, which utilized numerous kinds of measurements, was based in part on the assumption that much of human behavior was innate. That is, people behaved the way they did because different body types and different “races” were biologically predisposed to this type of behavior.

With regard to individual behavior, there were some scientists who felt that sociopathic and psychopathic behaviors, insanity, dementia, and personality traits were all correlated with the size, shape, and configuration of the skull. They felt that given enough data they could be able to accurately predict things like criminal behavior by measuring the skull and recording the locations of different bumps and irregularities.

With regard to populations, European scientists assumed that Europeans were superior in all ways to other peoples. Part of that superiority, they reasoned, must lie in the larger brain of Europeans and in the shape of European skulls. They thus measured lots of skulls to provide data to prove this hypothesis. When the data didn’t fit their model of supposed European superiority, some of them simply modified their numbers to make it fit.

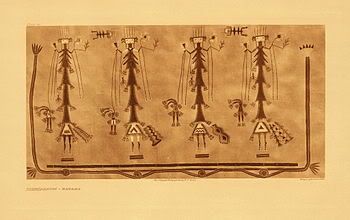

For those who were studying human skulls and attempting to make correlations between behavior and skull shape, the Indian people along the Columbia River and the Northwest Coast area posed an interesting problem: they practiced cranial deformation. They would bind the head of infants which would create an elongated skull. Within the context of these Indian cultures, the elongated skulls-sometimes call flatheads-were the mark of nobility. People with roundheads were usually slaves.

For those who had postulated that the shape of the human skull dictates personality and intelligence, modifying the shape of the skull through cranial deformation should have resulted in low intelligence. Yet, the Indians with deformed skulls, including Chinook chief Comcomly, seemed to be intelligent. Thus there was a great deal of interest in obtaining deformed skulls for further study.

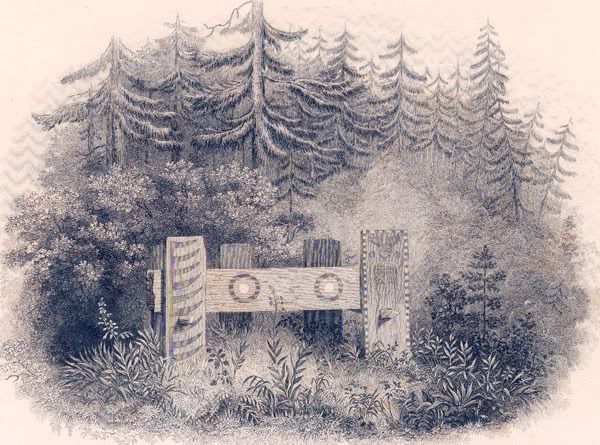

Shown above is a painting by Paul Kane showing a Chinook woman with a flattened skull and an infant with a bound head which will produce the deformation. In 1846, Kane went to Memaloose Island in the Columbia River where he robbed a traditional Chinook funerary canoe of its skull.

About Comcomly:

When the Corps of Discovery, led by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, reached the mouth of the Columbia River in November of 1805, Chinook Chief Comcomly was one of those who greeted the party. Lewis and Clark gave Comcomly a medal and a flag.

In 1811, Comcomly provided help to John Jacob Astor’s Pacific Fur Company when they established their new trading post at Fort Astoria. Two years later, Pacific Fur Company trader Duncan McDougall married the daughter of Chinook chief Comcomly. This marriage increased Comcomly’s access to goods and it also brought him prestige. For the Americans, the marriage provided them with valuable trading connections with Indian families as well as some security.

At the marriage between Comcomly’s youngest daughter Raven and the trader Archibald McDonald, Raven walked the 300 yards from her house to a waiting canoe on a carpet of furs. These furs were then bundled up and given to McDonald as a gift. In return, McDonald and the other traders showered Comcomly with European manufactured trade goods, thus increasing his wealth and standing with the native society.

On one of his trading trips to the Hudson’s Bay Company trading post at Fort Vancouver, he was accompanied by many warriors and by about 300 slaves. Some of the slaves placed beaver and otter skins on the path for him to walk on.

Comcomly died in a smallpox epidemic in 1830 at the age of 65. He was given a traditional Chinook canoe burial on Memaloose Island in the Columbia River. The Chinook custom was to place the dead body along with a number of prized possessions in a canoe which was then elevated in the trees out of the reach of animals.

The Theft of Comcomly’s Skull:

In 1834, Dr. Meredith Gairdner, a physician with the Hudson’s Bay Company post at Fort Vancouver, decided that he wanted to send back to England the skull of Chinook chief Comcomly.

Gairdner went to the Memaloose Island burial grounds at night in order to obtain Comcomly’s skull. He found, however, that the chief’s body was buried in a forest grave to deter theft by Europeans. It thus took considerable work to excavate the box which held the chief’s body. He then had to pry off the lid. What he found was a skeleton with the hair still on the chief’s flattened skull. He then decapitated the corpse and took it with him to Honolulu. From here he shipped it to John Richardson, a physician and naturalist in England. In his note to Richardson, Gairdner wrote of Comcomly:

“By his ability? Cunning? Or what you please to call it, he raised himself and family to a power and influence which no Indian has since possessed in the districts of the Columbia below the first rapids one hundred and fifty miles from the sea. When the phrenologists look at this frontal development, what will they say to this?”

Comcomly’s skull remained in the Royal Naval Museum in London for 117 years. Then, in 1952, it was sent to the Clatsop County Historical Society in Astoria, Oregon. Four years later, the Society loaned the skull to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. In 1972, Comcomly’s relatives insisted that the Smithsonian return the skull to them. It was then buried near Comcomly’s native village site at Ilwaco, Washington.

Leave a Reply