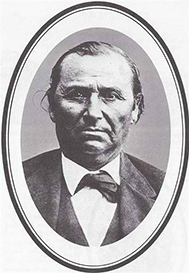

From the viewpoint of non-Indians, particularly government officials in the nineteenth century, a progressive Indian leader was one who advocated the assimilation of Indians into “mainstream” American culture. One of these progressive Indian leaders was Joseph LaFlesche.

Joseph LaFlesche was the son of a French fur trader and a Ponca woman. When he married an Omaha woman he was formally adopted into the Omaha Elk clan and was thus considered to be Omaha. When his adopted father, Omaha chief Big Elk, died in 1853, many people considered Joseph LaFlesche as principal chief of the Omaha.

While many Omaha considered Joseph LaFlesche a chief, and even the principal chief, the Americans and Joseph LaFlesche considered Logan Fontelle to be the principal chief. Historian Judith Boughter, in her book Betraying the Omaha Nation, 1790-1916, reports:

“Because his father was a French trader and he was never adopted into the tribe, Logan Fontelle probably did not qualify for chieftainship.”

Logan Fontelle was killed by a Sioux war party in 1855.

Joseph LaFlesche favored adopting American ways. For example, he refused to allow his four daughters to be tattooed in the Omaha fashion as he wanted them to be able to freely mingle in Euro-American society. He also encouraged the Omaha to build houses in the American style.

One aspect of American society which Joseph La Flesche opposed was alcohol. In 1856, together with the Indian agent for the reservation, he established an Indian police force for the purpose of eliminating alcohol on the reservation. This police force was headed by Ma-hu-nin-ga (No Knife).

In 1857, the Presbyterians, with the encouragement of Joseph LaFlesche, established a mission day school for the Omaha. The children were all given English names. The LaFlesche children attended this school.

At this same time, a group of Omaha under the leadership of Joseph La Flesche began to build American-style, two-story frame houses. For this reason, the other Omaha referred to them as “Make-Believe White Men.”

In 1858, chief Joseph La Flesche organized a great council of the Omaha because of rumors that the government was planning to reduce the size of their reservation. The council reaffirmed their commitment to the Americanization program, and strenuously opposed any reduction in the reservation.

The Omaha reservation in Nebraska had been established in 1854 when the Omaha ceded all of their lands west of the Missouri River to the United States. As a part of this treaty, the United States was to protect the Omaha from attacks by other tribes, particular the Sioux.

In 1860, a Sioux war party under the leadership of Little Thunder attacked the Omaha within sight of the Presbyterian mission. As a result of this attack, many Omaha left their villages. Joseph LaFlesche and other Omaha leaders met with the Indian Agent and demanded that their treaty’s clause which called for the United States to protect them from raids by other Indian nations be honored.

In exchange for ceding much of their land to the United States, the Omaha were to receive an annual annuity payment. In 1862, Joseph La Flesche began asking why most of their annuity was paid in paper money while the more rebellious tribes received theirs in gold and silver. According to historian Judith Boughter:

“He considered the practice unfair, since it made a $7,000 difference in the Omahas’ yearly income and since the government expected its payments in coin.”

In 1865, the United States asked the Omaha to sell 100,000 acres of their reservation in Nebraska to provide a new home for the Winnebago. In the treaty, negotiated by Joseph La Flesche, Standing Hawk, Little Chief, Noise, and No Knife, the Omaha were to receive $50,000 to be used by their Indian agent to improve their reservation. The Omaha were also to be provided with a blacksmith, a shop, a farmer, and mills for 10 years.

In 1866, the Indian agent for the Omaha Reservation accused chief Joseph LaFlesche with producing discord among the tribe, leaving the reservation without permission, lending money at usurious rates, encouraging the tribal police to inflict unfair punishments, and refusing to allow people to deal with licensed traders. The agent called for him to be deposed as tribal chief and to be banished. LaFlesche’s protector, the Presbyterian mission school superintendent, was then dismissed. LaFlesche and his family hastily fled from the reservation.

A few months later, the Indian agent agreed to allow LaFlesche to return to the reservation, but only if he agreed to be subordinate to the agent. Historian Judith Boughter reports:

“LaFlesche did return home, but he never again held a seat on the tribal council and apparently was recognized as a leader only among his band of followers in the young men’s party.”

Joseph LaFlesche had several wives and at least ten children. With Mary Gale, he had five children, including Susette LaFlesche (Bright Eyes) who became an Indian activist and Susan LaFlesche who became the first Indian woman physician. With Elizabeth Esau, he also had five children, including Francis LaFlesche, who became an ethnographer. Joseph LaFlesche died in 1888.

Leave a Reply