In 1825, Governor George Simpson of the Hudson’s Bay Company conceived the idea of selecting some Indian boys from the Columbia River tribes in present-day Washington and Idaho and sending them east to the Anglican mission school at Red River in Manitoba to be educated. His idea was that these boys could help in “civilizing” the tribes upon their return. Two teenage Indian boys – one from the Spokan in Washington and the other from the Kootenai in Idaho – were sent to the Red River School. The boys are renamed Kootenai Pelly and Spokan Garry. The name “Garry” was taken from the name of one of the directors of the Hudson’s Bay Company and the name “Pelly” from one of its governors. At the school, the boys were taught to read and write both English and French.

About the Spokan:

First, a note about spelling: I am using “Spokan” to indicate the tribe in order to avoid confusion with “Spokane” which is the name of a city in eastern Washington. Spokan is often translated as “Children of the Sun.”

The Spokan, a Salish-speaking people, were traditionally composed of three groups: (1) Upper Spokan who occupied the Spokane Valley; (2) Middle Spokan who occupied the Deep Creek and Four Lakes area; and (3) Lower Spokan who occupied the area around the Tchimokaine, Tumtum, and the mouth of the Spokane River. Traditionally, the overall Spokan territory extended from the head waters of the Chimokaine to the mouth of the Spokane River; down the south side of the Columbia as far as the mouth of the Okanogan; south to the head of the Snake River water shed; east to about the line of the present towns of Post Falls and Rathdrum.

As with other tribes along the Columbia River, fishing was an important economic activity. Downstream from Little Falls on the Spokane River, the Spokan would build a rock barrier across the river, and then place a willow-pole fish weir just upstream from this barrier. The fish were then speared and thrown to shore. This fishing site was also used by the Coeur d’Alene, Kalispel, Colville, Palouse, Sanpoil, and Sinkayuse.

While men traditionally fished for the salmon, only the women were able to obtain the lashings that bound the tripod of the fishing weir together. The men, therefore, were unable to build the weirs by themselves. Building fish weirs required the cooperation of women, thus the women had a crucial role in the important salmon fishing.

The salmon was dried in the sun and wind. The dried salmon would be pounded with a stone pestle in an oak mortar until it was finely pulverized. The salmon powder would then be tightly pressed into baskets lined with salmon skin. This dried, powdered salmon would keep for a long time.

The women usually prepared the fish. Once a woman had prepared the fish, it belonged to her and she made the decisions on how it was to be used. When salmon was used in trade, the trade items belonged to the women.

While hunting provided some of the Spokan nutrition, hunting is not always a dependable way of obtaining food. In order to ensure a successful hunt, individual hunters sought out spirit helpers and communal hunts required a hunt chief with experience, as well as an appropriate spirit guide. Before hunting, the men would often go through a sweat bath purification ritual and would make appeals to the animal spirits.

While much of the hunting focused on locally available big game-deer, elk, caribou-the Spokan would sometimes go on a communal buffalo hunt. This meant that they would travel from their home in eastern Washington, across northern Idaho, through western Montana, and cross the Rocky Mountains to the Great Plains. This meant that they would be trespassing into territory claimed by the Blackfoot and the Blackfoot would often object to this. Thus, the buffalo hunt was often an inter-tribal affair as alliances provided some protection against the war parties of the Blackfoot and other tribes. The Kootenai, for example, often joined with the Coeur d’Alene and Spokan for the buffalo hunt. The hunt would usually last about four weeks.

Trade was also a major economic activity for the Spokan. The Spokane Falls area often served as a major trading center. Trading activities were often timed to occur during the fishing harvests. Prior to the coming of the Europeans, common trade items included stone tools from the glass volcanics (obsidian, vitrophyre, and ignimbrite) and marine shells, most commonly dentalium and olivella. The shells were often cut into beads which were then used as trade goods. In addition, manufactured products such as coiled baskets, parfleches, and tanned buffalo hides were brought into the area.

Spokan Garry:

Spokan Garry and Kootenai Pelly returned to the northwest from the Red River School in 1829. Garry’s father, Illim-Spokanee, had died while the boy was at school, so the Spokan greeted him as a leader’s son who should be heard on matters affecting the welfare of this people. Spokan Garry brought with him the Christianity which he learned in school and preached it to the tribes in eastern Washington.

Garry’s preaching influenced leaders in other tribes. Soon after his return, for example, a young Nez Perce-Hol-lol-sote-tote, later known as Lawyer-heard Spokan Garry read from the Christian bible in Salish. Since Lawyer’s mother was Flathead (a Salish-speaking tribe), he was fluent in both Salish and Nez Perce. Lawyer was deeply moved and subsequently became Christian.

Soon after his return to the Spokan, Garry became recognized as a chief and acquired two wives: one from the Umatilla tribe and one from the San Poil tribe. His decision to take a second wife was viewed negatively by non-Indian missionaries.

With regard to his work as a native missionary preaching Christianity to the Indian people in the Upper Columbia area, Garry built a tule mat church and school along the Spokane River. He taught brotherly love, peaceful behavior, and humility. He also served as the translator for one of Francis Heron’s sermons at Fort Colville. In the audience were chiefs from the Spokan, Nez Perce, Coeur d’Alene, Kootenai, Pend d’Oreille, Sanpoil, and Kettle Falls tribes.

In 1836, Garry was involved in a large public Christian worship for the Spokan and Nez Perce at Loon Lake. Spokan Garry translated for the Spokan while a Nez Perce chief who understood some Spokan then translated from Spokan to Nez Perce.

In 1853, Governor Isaac Stevens met with the Spokan. Stevens wrote of Spokan Garry:

“Garry, the Spokane Chief, is a man of education, of strict probity and great influence over his tribe. He speaks English and French well.”

The treaties “negotiated” (some would say “imposed”) by Governor Stevens led to a great deal of unrest and set the stage for war. In 1854, a large intertribal council in Oregon’s Grande Ronde Valley is called by Yakama leader Kamiakin, Walla Walla leader Peopeo Moxmox, and Nez Perce war chief Apash Wyakaikt (Looking Glass). The tribes spent five days listening to Kamiakin’s account of what was happening to the Indian nations west of the Cascade Mountains. Kamiakin urged a confederacy so that the Americans (suyapos) could be fought with a united front. Kamiakin told the council:

“We wish to be left alone in the lands of our forefathers, whose bones lie in the sand hills and along the trails, but a pale-faced stranger has come from a distant land and sends word to us that we must give up our country, as he wants it for the white man. Where can we go? There is no place left”

Spokan leader Garry, Cayuse leader Stickus, and Nez Perce leader Lawyer felt that the Indians were not strong enough to wage war against the Americans. Among the Yakama, Teias and Owhi (both uncles to Kamiakin, and Teias was also Kamiakin’s father-in-law) opposed war.

The following year, Governor Stevens held a large treaty council at Walla Walla, Washington in which he announced his plans to establish two reservations: one would be located in Nez Perce country and would be for the Nez Perce, Cayuse, Walla Walla, Umatilla, and Spokan, and one in Yakama country for the Yakama, Palouse, Klikatat, Wenatchee, Okanagan, and Colville. The assembled tribal leaders disliked the Stevens’ proposal, so it was modified to include a third reservation: one to be located in Umatilla country for the Umatilla, Cayuse, and Walla Walla.

Following the treaty council at Walla Walla, Governor Stevens met with the Flathead, Pend d’Oreille, and Kootenai at Hell Gate and negotiated the treaty which would establish the Flathead Indian Reservation. In addition to the three tribes, the new reservation, according to Stevens’ vision, would also serve as home to the Coeur d’Alene and the Spokan.

By the end of 1855, the American vision called for the Spokan to leave their homeland and settle on either the Nez Perce or the Flathead reservations. Shortly after the treaties, Americans began their invasion of Spokan country looking for mineral wealth and paying little attention to any Spokan rights.

As a result of the treaties and American violations of Indian rights, war soon swept across the Plateau region. As a result Governor Isaac Stevens held council with some of the Columbia River tribes on the Spokane River in 1855. While the Americans were seeking to prevent the Columbia River tribes from joining the growing anti-American war, they heard the chiefs speak with some sympathy for the hostilities. In the rather stormy council, the Americans were unable to promise the Indians that the American army would not invade their territory. During the council, Spokan Garry told them:

“I think the difference between us and you Americans is in the clothing; the blood and the body are the same.”

As the war spreads, American forces under the command of Major Edward Steptoe were defeated by an intertribal war party with warriors from the Palouse, Coeur d’Alene, Spokan, Yakama, Pend d’Oreille, Flathead, and Columbia. Thus the Spokan were drawn into the war. Following the American defeat, the American forces swept though the Indians’ country from the Cascades to Lake Coeur d’Alene, attacking villages, burning provisions and supplies, taking hostages, and shooting and hanging Indians, with little regard to whether the Indians were actually hostile or friendly. The Americans defeated the Indians at the battles of Four Lakes and Spokane Plains. Two of Spokan Garry’s brothers were killed in these battles.

Following the battles of Four Lakes and Spokane Plains, Colonel Wright directed Spokan Garry to send messengers to chiefs Moses, Big Star, Skloom, and Kamiakin and inform them that they should come in for a conference. Later Colonel Wright reported:

“I warned them that if I ever had to come into this country again on a hostile expedition no man should be spared; I would annihilate the whole nation.”

After signing the treaties with the Spokan and Coeur d’Alene, Colonel Wright adopts a policy to hang individual Indians, demonstrating to the tribes what would happen to them if they ever broke the treaties they had signed.

In 1859, Spokan Garry petitioned military authorities and the Indian agent for a reservation for his people. Brigadier General W. S. Harney forwarded the request to the Secretary of the Interior with the following comment:

“In justice to these Indians this step should be adopted by our government; they already cultivate the soil in part for subsistence, and unless protected in their right to do so, they will be forced into a miserable warfare until they are exterminated.”

No action results from the request.

In 1866, a party of Spokan were hunting buffalo in Montana. During the hunt, they captured several horses from the Blackfoot. In retaliation, the Blackfoot killed a Spokan chief and captured 160 Spokan horses. The horse-poor Spokan then captured some non-Indian horses on their way home. In Missoula, Spokan Garry was arrested, but the Indian agent arranged for his release.

In 1872, the Colville Reservation was established by executive order of President Ulysses S. Grant for the Methow, Okanagan, Sanpoil, Nespelem, Lakes, Colville, Kalispel, Spokan, Coeur d’Alene, Chelan, Entiat, and Southern Okanagan. Once again there was little interest in providing the Spokan with their own reservation.

In 1874, Spokan Garry met with the Commandant of the Department of the Columbia. He was told that the government had no interest in giving the Spokan a reservation and that they should be careful not to make any trouble.

In 1880, the United States government held council with the Colville, Upper Spokan, Okanogan, Coeur d’Alene, and Lower Spokan just above the falls in Spokane. Nearly 4,000 Indians were present at the council and most did not have a reservation. Spokan Garry argued for a reservation for his people. The Americans promised them a new and ample reservation, but did not sign an agreement to that effect.

In 1881, the United States ordered the Spokan to move to a reservation west of the Columbia River or to take allotments. Chief Spokan Garry replied:

“What right have you to dictate to us? This is our country and we will not leave it.”

Instead of forcing the Spokan to move, a reservation is established for them by Presidential executive order.

In 1887, Spokan Garry asked the Indian Department to cede to his people as a reservation the land on both sides of the Spokane River from the city of Spokane to Tum Tum. The request was denied.

At the 1887 Treaty of Spokane Falls, Washington, non-reservation Spokan agreed to give up all claims to lands outside of the Spokane Reservation and to move to the Couer d’Alene Reservation in Idaho or to the Flathead Reservation in Montana. The United States agreed to help them in moving and finding new homes.

In 1888, Spokan Garry was at a temporary fishing camp away from his farm when non-Indians took over his farm and the crops that he had planted. When he returned home, the men told him to stay off. While Spokan Garry filed suit in an attempt to regain his farm, he died in 1892 before a decision was reached. The pattern of non-Indians taking over farms already being cultivated by Indians is fairly common at this time, and the Indians have little legal recourse.

Garry was about 81 years old at the time of his death. During the last years of his life, Garry was homeless and lived in poverty. The crude tent which had been his last shelter from the winter’s snow and cold became his mortuary.

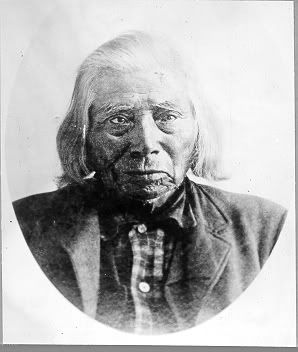

A photograph of Spokan Garry is shown above.

Leave a Reply