The oldest, largest, and most representative group of American Indians and Alaska Natives is the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI). Many people also feel that it is today the most politically influential Indian organization in the United States. The NCAI started in the 1940s.

In 1944 a group of 22 prominent Indians-20 of whom worked for the Bureau of Indian Affairs-met at the Chicago YMCA to begin organizing a national Indian organization. Those attending this organizational meeting include:

Arthur O. Allen (Sioux), Ruth Bronson (Cherokee), Mark L. Burns (Chippewa), Cleo D. Caudell (Choctaw), Ben Dwight (Choctaw), David Dozier (Pueblo), Amanda H. Finley (Cherokee), Ken FitzGerald (Chippewa), Roy E. Gourd (Cherokee), Lois E. Harlin (Cherokee), Charles Heacock (Sioux), Erma O. Hicks (Cherokee), George LaMotte (Chippewa), Leona Locust (Cherokee), Carroll Martell (Chippewa), Randolph N. McCurtain (Choctaw), D’Arcy McNickle (Cree), Charlotte Orozco (Chippewa), Peter Powlas (Oneida), Ed Rogers (Chippewa), Harry L. Stevens (Apache), and Archie Phinney (Nez Perce).

Of those attending, only Dwight and Dozier did not work for the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

The group drafted a constitution and bylaws based on those of the Federal Employees Union No. 780. They agreed that active membership should be limited to Indians, but left the definition of “Indian” to the tribes. While the new organization sought to represent the actual diversity of American Indians, it used the government’s list of tribes as its organizational base.

Mark L. Burns was selected as temporary president with Charles Heacock and Ed Rogers as first and second presidents. The provisional executive committee included David Dwight, D’Arcy McNickle, David Dozier, Ruth Bronson, Arthur Allen, and George LaMotte.

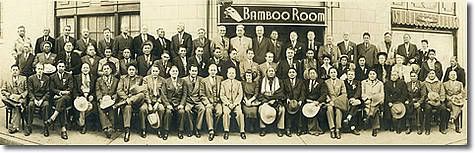

A few months later in Denver, Colorado, 80 Indians from more than 50 tribes in 27 states gathered to form the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI). The new organization emphasized both tribal and civil rights for Indians. At a time when American Indian policy was once again beginning to return to an emphasis on assimilation, the newly formed NCAI did not oppose the voluntary assimilation of individual Indians into mainstream American society as long as it did not threaten the survival of tribal governments and the tribes themselves.

Those who attended this organizational meeting tended to be progressive, younger Indians who held positions of leadership within their tribes. They were literate and accustomed to dealing with bureaucracies. The participants attended the meeting, however, as individuals, not as tribal appointees.

The Preamble to the Constitution and Bylaws stated that the purpose of the NCAI was

“to enlighten the public toward a better understanding of the Indian race; to preserve cultural values; to seek an equitable adjustment to tribal affairs; to secure and to preserve rights under Indian treaties with the United States; and to otherwise promote the common welfare of the American Indians.”

Judge Napoleon B. Johnson (Cherokee) was elected as president and Dan Madrano (Caddo) was chosen as secretary. The executive committee was composed of Stephen DeMers (Flathead), Henry Throssell (Papago), William Firethunder (Sioux), Luke Gilbert (Sioux), Howard Gorman (Navajo), D’Arcy McNickle (Flathead), Archie Phinney (Nez Perce), and Arthur Caswell Parker (Seneca).

The delegates passed 18 resolutions to guide the NCAI for the next year. These resolutions addressed three broad themes: sovereignty, civil rights, and political recognition for all Indians. There were two immediate concerns: (1) the establishment of a claims commission through which the tribes could litigate old land claims against the United States, and (2) the securing of voting rights for Indians in New Mexico and Arizona.

The second annual convention of the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) was held in 1945 in Browning, Montana on the Blackfeet Reservation. Delegates from 22 tribes attended. The NCAI adopted a policy of electing at least one woman to the executive council each year and Lorene Burgess (Blackfoot) was elected to the council.

The NCAI began with a close association to the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the policies of former Commissioner of Indian Affairs John Collier. At this second meeting, Robert Yellowtail (Crow), an outspoken critic of both the BIA and John Collier, was elected to the council. D’Arcy McNickle (Cree enrolled Flathead and a BIA employee) put forth a resolution to forbid BIA employees from holding elective positions in the NCAI. The resolution passed.

The Browning location was selected because it is in the heart of Indian country and members felt that it would help symbolize Indian unity. However, the remote location meant that the meeting generated very little public relations in the non-Indian media.

By 1949, the NCAI had grown significantly and its annual convention, held in Rapid City, South Dakota, was attended by 212 delegates. Louis Bruce (Sioux/Mohawk) was hired as executive director. At this convention the NCAI passed resolutions protesting the realignment of BIA in which 40 district offices had been closed and 11 area offices created.

Since NCAI was a lobbying organization and as such was not tax exempt it had been hindered in its fund raising efforts. Following the convention a separate organization-NCAI Fund, Inc.-was created to help in fund raising. However, this did not pass muster with the Internal Revenue Service and its name was changed to Arrow, Inc. The trustees for Arrow, Inc. were to be appointed by the NCAI business committee.

Over the next 60 years, the NCAI continued to develop its skills in lobbying Congress and the governmental bureaucracy. According to its website:

Over a half a century later, our goals remain unchanged. NCAI has grown over the years from its modest beginnings of 100 people to include member tribes from throughout the United States. Now serving as the major national tribal government organization, NCAI is positioned to monitor federal policy and coordinated efforts to inform federal decisions that affect tribal government interests.

Now as in the past, NCAI serves to secure for ourselves and our descendants the rights and benefits to which we are entitled; to enlighten the public toward the better understanding of the Indian people; to preserve rights under Indian treaties or agreements with the United States; and to promote the common welfare of the American Indians and Alaska Natives.

Their current issues and concerns include:

Protection of programs and services to benefit Indian families, specifically targeting Indian Youth and elders

Promotion and support of Indian education, including Head Start, elementary, post-secondary and Adult Education

Enhancement of Indian health care, including prevention of juvenile substance abuse, HIV-AIDS prevention and other major diseases

Support of environmental protection and natural resources management

Protection of Indian cultural resources and religious freedom rights

Promotion of the Rights of Indian economic opportunity both on and off reservations, including securing programs to provide incentives for economic development and the attraction of private capital to Indian Country

Protection of the Rights of all Indian people to decent, safe and affordable housing.

Leave a Reply