The Spanish entrada (entrance) into the American Southwest began during the sixteenth century with explorers who were driven by greed. The Spanish hunger for gold and other fast wealth was justified in their own minds by their religion: their attempts to harvest souls for their religion justified their brutality toward the native peoples they encountered. They had absolutely no doubts about their own cultural and religious superiority. Not only did they have no respect for the Indian cultures which they encountered and the hospitality which was freely offered them, but they expected the Indians to recognize their superiority and to serve them as porters, concubines, and slaves.

At the beginning of the Spanish entrada, it is estimated that the Hopi, whose villages were the western-most of the Indians classified as Pueblos, had a population of about 29,000. The Hopi were not a politically unified group, but lived in several autonomous villages in Northern Arizona.

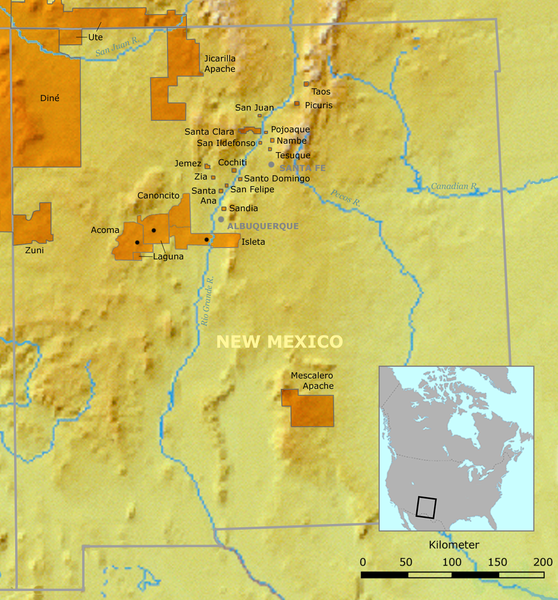

First contact with the Spanish invaders came in 1540. A Spanish expedition under the leadership of Francisco Vásquez de Coronado was making a sweep through the Southwest in search of the mythical Seven Cities of Cibola. The expedition came north from Mexico with a force of 330 Spaniards (most of whom are mounted soldiers) and 1,000 native allies. At Zuni in New Mexico, the Spanish waged a fierce hour-long battle in which they captured the village and the Indians fled into their stronghold at Thunder Mountain. The Spanish, who were starving, quickly seized the Zuni food supply.

After capturing Zuni, Coronado sent an expedition under the command of Captain Pedro de Tovar to make contact with the Hopi who had a tradition of trading with the Indian nations of the Colorado River area. The Hopi met the Spaniards at the town of Kawaika-a with coldness. The Hopi were in battle formation and drew a line on the ground with sacred corn pollen telling the Spaniards not to cross it. There was a short battle that was won by the Spaniards.

The next contact which the Hopi had with the Spanish came in 1583. Spanish conquistador Antonio de Espejo and his soldiers had taken formal possession of Zia Pueblo in New Mexico and the land around it for the King of Spain. The party then moved to El Morro and then to the Zuni. Travelling with 80 Zuni, the Spanish made contact with the Hopi village of Awatobi in Arizona. A combined force of Hopi and Navajo warriors met the Spanish in a show of strength and unity, but the Spanish forced both groups to make peace with them.

At the Hopi village of Tusayan the Spanish were presented with 4,000 cotton blankets, some of which were colored and some of which were white. The Spanish noted that the women wore cotton skirts that were embroidered with colored thread.

Espejo also noticed that the Hopi were painting their bodies with mineral pigments. With the help of Hopi guides, the Spanish visited the Hopi mines which were located in Yavapai territory. The mines were located in the Jerome Mountains and had been mined by the Yavapai for centuries. The Spanish find that the mine shafts burrowed deep into the mountain, but they were disappointed to find that the mines contained copper rather than silver and gold.

At the end of the sixteenth century, the Spanish invasion of the Southwest turned from one of exploration to one of colonization. With colonization came Spanish rule. Under the reasoning of the Discovery Doctrine Spain, as a Christian nation, was entitled and perhaps obligated to rule over all non-Christian people which it encountered. Thus, the Spanish took possession of Pueblo lands and peoples.

The first colonizing efforts came in 1598 when Juan de Oñate led a large colonizing party-129 soldiers and their families, 10 Franciscan missionaries, 83 wagons, 7,000 cattle, sheep, and goats-into New Mexico and established a colony at San Juan in the upper Rio Grande valley. The Spanish brought with them over 1,500 head of horse and mules: 1,007 horses, 237 mares, 137 colts, and 91 mules.

Meeting with leaders from 30 pueblos, Oñate took formal possession of New Mexico for the Spanish and ignored any possible Indian ownership of the land. He took possession of Pueblo lands in the name of the Christian King of Spain and for the benefit of any of the Spanish colonists with him who might want to exploit them. The Spanish warned the Pueblo leaders that they must accept baptism and instruction in Christian doctrine. If they failed to do this, then the Spanish would inflict physical punishment upon them and they would suffer the eternal torment of hell afterwards.

In Arizona, Oñate demanded that the Hopi give formal submission to the King of Spain. The Hopi superficially obeyed, hoping for a hasty departure of the Spanish troops.

Later that year, a small Spanish group under the leadership of Captain Marcos Farfan de los Godos set out with Hopi guides to the Indian mining areas in the San Francisco Mountains. Here they encountered Jumano settlements and they persuaded the Jumano to guide them to the mines. They found mines which were being operated by the Yavapai. The ores extracted from the mines were used as pigments and were considered by the Indians of the area to be a valuable trade commodity. The Spanish immediately laid claim to the mine.

In 1599, the Spanish destroyed the pueblo of Acoma in New Mexico after a native upraising. All Acoma adults were indentured for 20 years and all of the men had one foot hacked off. Two visiting Hopi, whose villages were to the west of Acoma, had one hand cut off so that others among their people would understand what happens to those who do not submit to Spain.

The Spanish, like many other European colonists, justified their taking of Indian goods and souls by giving the Indians the “gift” of Christianity. The first Christian missionaries arrived among the Hopi in 1628 in the form of 30 Franciscans. These men had come to the Americas specifically to convert the Indians to both their religion and their culture. They established missions at the Hopi villages of Awatobi, Oraibi, Shungopovi, Mishongnovi, and Walpi. They also attempted to convert the Navajo. The following year, the Spanish missionaries arrive at the Hopi village of Awatovi.

In 1629, the Franciscan Spanish missionaries renamed mountains which are sacred to the Indians after their patron saint: San Francisco Peaks.

In 1630, the Spanish constructed their Catholic church on top of a kiva (an underground ceremonial room) at the Hopi village of Awatovi. This symbolized to both the Catholic priests and to the Hopi that Christianity was to be dominant.

In 1655, some of the Pueblos lodged a formal complaint against the excesses committed by the Franciscan fathers. In response to the complaint, Father Guerra searched homes in search of feathers or idols. In the Hopi village of Shongopovi, the Spanish priest found Juan Cuna in possession of a katsina doll. The Spanish Inquisition had ordered Indian religions to be destroyed, and so Father Guerra publicly whipped Juan Cuna, poured turpentine over his wounds, and ignited it, burning him alive.

Katsinas (also spelled Kachinas), for the Hopi people in Arizona, are the spiritual essence of everything that is. Beginning in December each year, the Katsinas come to live for a while with the people. From December through July the Katsinas will come and go from the kivas (underground ceremonial rooms). To teach the children about the many different Katsinas, the Hopi carve tihu or dolls which represent different Katsinas. These tihu are not dolls to be played with, but hung from a wall or beam as a valuable possession.

In 1680, Pueblo spiritual leader Popé leads a revolt against the Spanish. By coordinating and uniting several Pueblos, the Indians defeated the Spanish. The Franciscans were driven out and the Pueblos set about re-establishing their religions. Among the Hopi in Arizona, the kivas were rebuilt using materials from the destroyed churches. At this time, the Hopi also began to use church bells in some of their ceremonies. For the Hopi, the use of the church bells symbolized the superiority of their religion over Christianity.

The Spanish soon began the process of re-conquest and as a result there were a number of population shifts within the Southwest. In Arizona, the Hopi village of Walpi, fearing Spanish reprisals from the Pueblo Revolt, moved from a lower terrace to a more defensive position on top of First Mesa. People from the New Mexico Pueblos fled the returning Spanish to resettle among the Hopi.

The Hopi village of Walpi is shown above.

While the Hopi population was estimated at 29,000 at the beginning of the Spanish entrada, by 1690 it had decreased to 14,000 due to diseases brought by the Europeans.

In 1699, Espleta, the chief of the Hopi pueblo of Oriabi, led a delegation of about twenty to meet with the Spanish governor of New Mexico. Espleta proposed to the governor that they should agree that their two nations live in peace and recognize the other’s right to its own religion. The governor refused to accept these terms.

In 1699, the Spanish attempted to reoccupy the Hopi villages with the occupation by Spanish priests at the village of Awatovi. The following year, the Hopi attacked and destroyed the Spanish-occupied village of Awatovi. The Spanish priests and their male converts were sealed in a kiva and then suffocated by having hot ground chilies poured in through the roof opening. The women and children were taken to other Hopi villages. Some of the Hopi survivors from Awatovi were taken in by the Navajo where they founded the Tobacco Clan.

A group of Tewa from New Mexico sought refuge among the Hopi in 1702. The Hopi chief did not fulfill the promise of land until they demonstrated their prowess. The Tewa defeated a Ute attack and were given a site on First Mesa where they built the village of Hano.

In 1716, a Spanish army under Governor Felix Martinez attempted to make the Tewa who sought refuge among the Hopi return to their pueblos in New Mexico. At First Mesa in Arizona, the Tewa in the village of Hano refused the Spanish request. Feeling that the climb to the top of the mesa to capture the Tewas would be costly, Martinez ordered Tewa crops to be destroyed and Tewa livestock to be killed. Some of the people who had fled from Jemez following the Pueblo Revolt of 1696 did return after the Spanish attack.

In 1775, Silvestre Vélez de Escalante, the missionary priest at Zuni Pueblo, received a request from the Spanish governor to report on the possibility of a land route between Santa Fe and Monterey (the Spanish capital of California). In addition, he was to report on a new plan for the subjugation of the Hopi. The priest and a small party traveled to the Hopi pueblos of Walpi and Oraibi. When he attempted to talk to the Hopi at Oraibi he received a hostile reception.

The following year, Spanish missionary Francisco Garces, stationed at the Mission San Xavier del Bac near Tucson, journeyed north to present-day Tuba City, Arizona . Here he encountered a settlement of Yavapai. A few miles away was the Hopi pueblo of Moenkopi which he describes as “half-ruined” and recorded the name as “Muqui conave.”

Another group of Spanish explorers led by the Francisans Fray Francisco Domínguez and Fray Vélez de Escalante approached the Hopi from the North. With the help of Paiute guides they were shown a road which led from Utah to the Hopi town of Oraibi. The Spanish followed the road to Oraibi where they received a friendly welcome and were given food. They then travelled to Second Mesa where they are told that the people of Shongopovi and Mishongnovi were willing to be friends, but they had no desire to become Christians. On First Mesa they spend the night at the Tewa-speaking pueblo of Hano. Here they met with a number of Hopi leaders and attempted to persuade them to travel to Santa Fe, but the Hopi leaders refused.

By 1780, the Hopi pueblos had now gone three years with no rain. They harvested only 800 bushels of corn and beans. While the Hopi population had been estimated at 7,494 five years earlier, it was now only 798. Five years earlier, the Hopi had had an estimated 30,000 head of sheep, now they had about 300. In addition, a smallpox epidemic swept through the Southwestern Pueblos and killed many Hopi.

In 1781, the Spanish planned to persuade the Hopi to relocate to New Mexico by sending converted Hopi and other Christian Indians to them. These Indians, ostensibly there for trade, would then be able to convince the Hopi to relocate in New Mexico. The plan failed. After this, the Spanish showed little interest in the Hopi and they lived relatively free from European influences in their lives until their homelands were acquired by the United States.

Navajo/Hopi land as a small child through oral history (oral history, gasp!) from my mother who was born (1920s) and raised on the Navajo reservation. She said that when the Spaniards first rode in the Navajo and Hopi greeted them and held up fruit to offer as a friendly gesture, she said the Spaniards cut off their hands holding the fruit.

Nice.

She said it was war after that.

I’m pretty sure she didn’t learn this at boarding school.