The Crow Reservation in Montana was first defined by the United States government at the Fort Laramie Treaty Council of 1851. Subsequently, the Indian Office (later known as the Bureau of Indian Affairs) assigned Indian agents to administer the reservation. In 1902 Samuel G. Reynolds became the Indian agent for the Crow reservation and began to implement a program of self-sufficiency. He cut off all tribal rations and began to abolish the tribal farms which had been collectively farmed by the Crow. He announced that he would discontinue the practice of meeting with the tribe in a council or powwow. Reynolds’ authoritarian policies were carried out in part by Big Medicine, a tribal police officer.

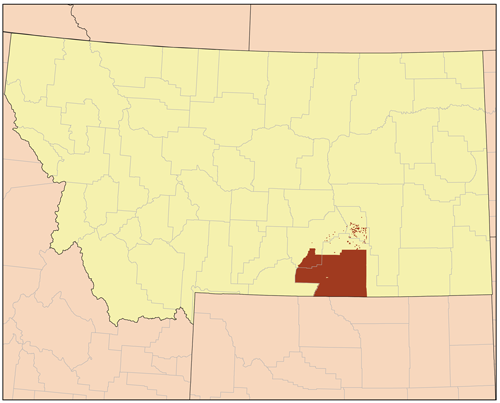

The location of the Crow Reservation is shown in the map above.

Following federal Indian policies that called for the break up of tribal held lands so that these lands could be developed by non-Indians, the sale of “unused” land on the Crow reservation was unilaterally altered in 1904. Ignoring Indian protests and concerns, Congress ratified the new plan to give Indian land to non-Indians. The following year, the Crow Reservation was allotted and Crow land began to pass out of Crow control.

In 1907, journalist Helen Grey met with the Crow in Lodge Grass, Montana where she heard their grievances against Indian agent Samuel Reynolds. Reynolds, angered by the protests against him, ordered Grey off the reservation. She travelled to Sheridan, Wyoming where she expected five Crow leaders to meet her and accompany her to Washington. However, the Crow leaders – Spotted Rabbit, Holds the Enemy, Joe Cooper, Packs the Hat, and Yellow Brow – were arrested and told that they could not leave the reservation without the permission of the agent. Grey travelled alone to Washington where she met with President Theodore Roosevelt, Secretary of the Interior James R. Garfield, and Indian Commissioner Francis Leupp.

At this time, there was little concern about the civil rights of Indians and the right to travel freely even though several court cases had affirmed these rights. Indian agents, such as Reynolds, tended to ignore court decisions and assume that American laws applied to Indians only when convenient to the interests of non-Indians, and particularly to non-Indian corporations such as those that leased Indian lands.

Upon her return to Montana, Helen Grey entered the Crow Reservation to attend some ceremonial dances. Indian agent Reynolds had her arrested. Later, a grand jury in Helena, Montana would hold a hearing on charges that Grey had solicited money from the Crow for her Washington trip. Reynolds declared a smallpox quarantine around the reservation and thus prevented any Crow from testifying before the grand jury.

In 1907, at a council with the Crow regarding the unoccupied lands on the reservation, Curly, a warrior and a former army scout, said:

“The land, as it is, is my blood and my dead; it is consecrated, and I do not want to give up any portion of it.”

In 1909, Crow leaders contacted Washington attorney Charles J. Kappler who represented tribes with complaints against the government. The Crow prepared a petition asking that the firm of Kappler and Merillat be appointed to represent them before Congress and governmental agencies. In 1910, Indian Commissioner Robert Valentine rejected this petition, claiming that there was no reason for the Crow to have counsel.

In general, Indian tribes were denied the right to their own legal counsel based on two lines of reasoning. First, they could use the attorneys already employed by the United States government, so having a private attorney was a waste of money. There was little concern about potential conflict of interest regarding having an attorney who actually works for the entity that is being sued. Second, many times the Commissioner of Indian Affairs did not feel that the tribes had any legitimate complaints and therefore legal counsel was not needed.

Indian Samuel G. Reynolds moved on, but the Crow Reservation remained, its administration subject to the whims and fancies of whatever non-Indian was appointed to the position of agent.

In 1919, the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs held a hearing on the boundaries of the Crow Reservation. When the reservation was established, the United States had met in council with only one of the three Crow tribes and had thus determined the Crow Reservation boundaries based on the traditional homelands of the Mountain Crow. Crow leader Robert Yellowtail testified:

“Mr. Chairman, your President yesterday assured the people of this great country, and also the people of the whole world, that the right of self-determination shall not be denied to any people, no matter where they live, nor how small or weak they may be, nor what their previous conditions of servitude may have been.”

He went on to say:

“I and the rest of my people sincerely hope and pray that the President, in his great scheme of enforcing upon all the nations of the earth the adoption of this great principle of the brotherhood of man and nations, and that the inherent right of each one is that of the right of self-determination, I hope, Mr. Chairman, that he will not forget that within the boundaries of his own nation are the American Indians, who have no rights whatsoever-not even the right to think for themselves.”

His words continue to ring true today.

Today, the Crow Reservation is the fifth largest reservation in the U.S. in terms of area. The Crow tribe has 11,000 members with about 8,000 living on the reservation. Most of the tribal members-85%–speak Crow as a native language and it is the official language of the tribe.

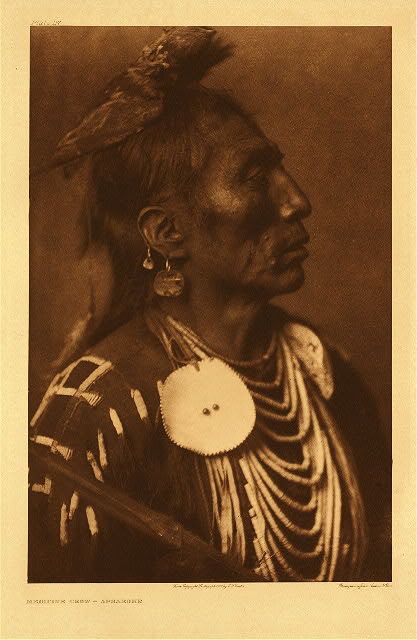

A photograph of Medicine Crow by Edward Curtis is shown above.

Leave a Reply