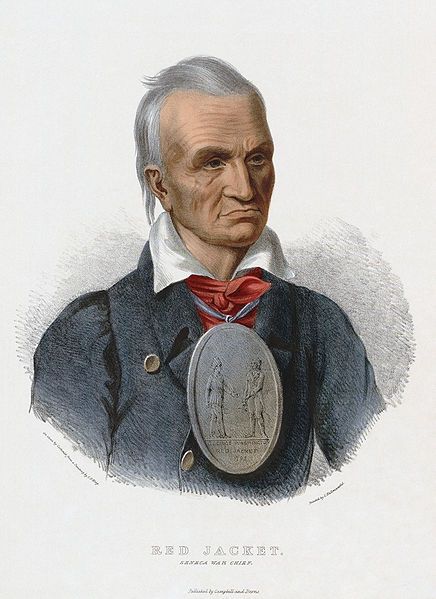

When the Europeans first encountered the Indian nations of North America they assumed that leadership must be inherited through the male line. That is, the “king” was always the son of the previous “king.” The idea of matrilineal inheritance-that is, inheritance through the female line rather than the male line-was inconceivable and baffling to the Europeans, even though it was common among Native Americans. For most Indian people, on the other hand, the idea that leadership should be based on genetics or biological inheritance was ludicrous. Leadership, according to most tribal traditions prior to the European conquest, was based on wisdom, skill, experience, and oratorical skill.

Potawatomi Background:

The tribes of the Three Fires Confederacy-Ojibwa, Ottawa, Potawatomi-were once a single people living in the east according to oral tradition. They moved westward from the Atlantic seaboard following the St. Lawrence River and then into the Great Lakes area. At the time of separation, the tribes were living in the area of the Straits of Mackinac. The Potawatomi moved south into present-day Michigan. It is estimated that the three tribes may have separated as late as 1550.

While the Potawatomi village chief usually came from one clan, the position was not inherited. Instead, the village council would select the chief from several possible candidates. The actual power of the chief was determined by personal influence as the chief held no formal authority. Part of this influence rested on the spiritual power which the chief controlled.

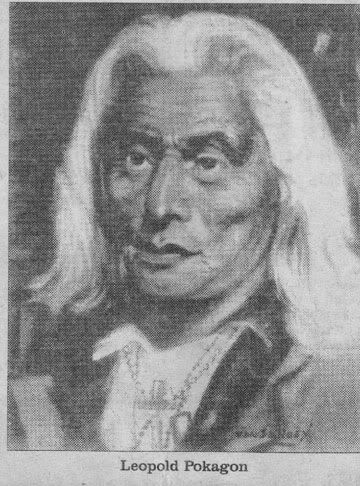

Leopold Pokagon:

During the nineteenth century, the Potawatomi were under pressure from the United States to leave their traditional homelands and re-establish themselves in the Great Plains west of the Mississippi River. The Americans also demanded that they become Christian and the Supreme Court declared that the payment they would receive for their lands was the “gift” of Christianity.

With regard to leadership, the United States preferred to deal with dictatorships rather than democracies and so it sought to set up and financially support Indian leaders loyal to the U.S. rather than to the Indian people. Whenever possible, the United States sought to ignore the traditional participatory democracies of the Indian people they were attempting to remove.

One of the Potawatomi tribal leaders who emerged during the first part of the nineteenth century was the man whom the Americans called Leopold Pokagon.

Leopold Pokagon was not born Potawatomi, but being born into a tribe or being able to prove a certain amount of blood quantum to be a tribal member was of no concern to the tribes. These are concerns that would be later forced upon Indian people by the U.S. government. Pokagon was born Anishinabe, one of the Three Council Fires, and had been adopted into the Kitichigumi (Great Lakes) Potowatomi clan. The Kitichigumi was the largest and most influential Potawatomi clan of the St. Joseph River valley region. He married the daughter of Topinabee, one of the leaders of the St. Joseph Potawatomi. The name “Leopold Pokagon” was not, of course, a traditional tribal name, but rather it was a name he assumed when he was baptized.

During the 1820s the United States continually pressured the Potawatomi to give up their lands and move somewhere else. The United States negotiated treaties with the Potawatomi in 1821, 1825, 1826, 1828, and 1829 in which the tribe was pressured to give up more and more land and agree to move. It was at the 1825 treaty council in Wisconsin where Leonard Pokagon first enters into the American historical record. In the 1825 treaty council, hosted by William Clark (of Lewis and Clark fame), lavish gifts and promises were heaped upon the Indian delegates. While the treaty council was held ostensibly to promote peace among the tribes, the primary motivation for the council was to promote the fur trade. The treaty also sought to establish firm boundaries regarding tribal lands. While the boundaries were agreed upon in principle, the final determination of the actual boundaries was to be determined by the United States.

The fur trade was an important element in the American strategy for obtaining Indian land. Following the suggestion of Thomas Jefferson, the United States licensed traders simply extended almost unlimited credit to both the tribes and to individual tribal members. Then the traders would turn to the U.S. government who would collect the debts by forcing the Indians to give up more of their lands.

Christianity also played an important role in federal policies regarding Indians. The federal government wanted to force all Indians to become Christians, and more importantly to become Protestant Christians (Catholics at this time were viewed as “atheistic papists” who were only a step or two above the pagan Indians.) The Baptist missionary Isaac McCoy had been initially welcomed by the Potawatomi because of the promise of economic advantages of having a mission and becoming Christian. It was soon apparent, however, that McCoy was an advocate of Indian removal. From the Baptist viewpoint, the only way to save the Potawatomi from the corrupt influence of the American settlers was to have them move far away.

Leopold Pokagon was strongly opposed to removal. Thus, in 1830 he went to Detroit where he met with Father Gabriel Richard and formally requested that a blackrobe (the Indian term for a Jesuit priest which referred to the black cassock which they wore) be assigned to them. Pokagon felt that an affiliation with the Catholic Church would be a countervailing force to the Baptists and thus they would be an important ally in their fight against removal. By converting to Catholicism, the St. Joseph River Valley Potawatomi assumed a new identity and would become known as the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi.

In 1833, the Americans wanted more Potawatomi land, so they convened a treaty council in Chicago. Here the Americans recognized Billy Caldwell and Alexander Robinson, both of whom were loyal to the United States, as Potawatomi chiefs and negotiated the land cessions with them. Under the treaty, the Potawatomi were to remove to Missouri where they would receive five million acres of land and would be provided with annuities for twenty years. The treaty agreement also covered all debts to the traders. However, Leopold Pokagon emphatically opposed giving up more land. Pokagon was successful in negotiating an amendment which would allow his band to remain in Michigan. In the negotiations he emphasized that he and his people were Catholics and this helped secure the amendment.

In 1835, the Potawatomi moved into the Platte Country of Missouri and soon found that American settlers waned them to move out of the area. Two years later these Potawatomi broke into two groups: one moved to the area of Council Bluffs, Iowa and the other moved to the area of Linn County, Kansas.

In 1838, the Potawatomi who had remained in Indiana were forced to move to Oklahoma. Soldiers simply surrounded the Indians and forced them to march without provisions or possessions. Survivors called this the Trail of Death.

In 1839, Pokagon relocated from the village near the Indiana-Michigan border to land he purchased on Silver Creek (near present-day Dowagiac, Michigan). He used the monies paid to him from the Treaty of Chicago to purchase lands for his people and he patented the land in his name, thus providing his people with a legal title the same as the American settlers. Here they managed to resist calls for their removal, including attempts at using military force to remove them. Leopold Pokagon died in 1841. Descendents of his band still reside in the area and are known as the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians (Pokégan Bodéwadmik débéndagozwad).

Leave a Reply