The European invasion of the Oregon Country began in the late eighteenth century and intensified in the early nineteenth century. In 1818, the United States and the United Kingdom, ignoring any possibility of the sovereignty of Indian nations and relying on the legal concept of the Discovery Doctrine (stating that Christian nations have a right, if not an obligation, to rule over non-Christian nations), signed a treaty declaring Oregon Country to be a joint occupation area. Under this treaty, both the United States and the United Kingdom could claim land and both were guaranteed free navigation throughout.

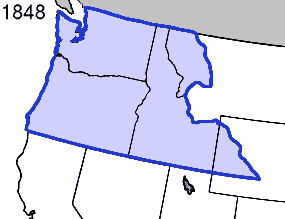

Oregon Country was the American name for the region; the British called it the Columbia District. The area stretched from the Pacific Ocean to the Continental Divide; it was bounded in the north at Fort Simpson in what is now British Columbia; and in the south at what would now be the Oregon-California border. It encompassed the present-day states of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho; western Montana; and the Canadian province of British Columbia.

While the initial invasion of the Oregon Country was led by fur traders, the English Hudson’s Bay Company, the Canadian Nor’Westers, and the American Astorians, by the 1830s the missionaries began to arrive.

The first of the missionaries was Jason Lee who had been originally sent by the Methodist Missionary Board to establish a mission among the Flathead in western Montana. The Flathead had astonished the Christian world by sending expeditions to St. Louis asking for missionaries. The Flathead had learned about Christianity, and more importantly, about the power of the Black Robes (Jesuit priests) from Iroquois employed by the fur trade. They had come to St. Louis specifically seeking a Black Robe, but the Methodists had decided to reach the Flathead first and bring them the true Christian religion.

Jason Lee met with the Flathead and the Nez Perce at the Green River Rendezvous in Wyoming. He found the Indians deeply unsettling. He concluded that the Indians were slaves to Satan and to alcohol. Instead of establishing an Indian mission, he continued his journey west to Fort Vancouver, a Hudson’s Bay trading post. From here, he went to the Willamette Valley just north of present-day Salem, Oregon where he established a mission and a school in an area with relatively few Indians. There were, however, about a dozen Canadian settlers, former employees of the Hudson’s Bay Company, with Native American wives living in the area.

The Flathead’s request for a missionary was answered in 1840 with the Jesuit Pierre-Jean De Smet. In 1840, he was welcomed into a camp of Flathead and Pend d’Oreilles. De Smet envisioned a new Indian society similar to medieval Europe in which the Indians would become Catholic farmers subservient to the Church.

In Oregon, Methodist missionaries set up a mission and farm on the Clatsop Plains west of Fort Clatsop in 1840. The wife of an American settler in the area, Celiast Smith, was the daughter of Clatsop chief Coboway and was able to translate for the missionaries. Ideally, the missionaries wanted to be able to preach to the Indians in their own language, but they soon found learning the Chinookan languages such as Clatsop was beyond their abilities. The Chinookan languages include sounds which are difficult, if not impossible, for English-speaking adults to master. The missionaries, therefore, turned to Chinook Jargon, a pidgin language with a reduced vocabulary and no complexities of verb conjugation or noun declension. As a pidgin language, Chinook Jargon was designed to be learned by adults and to facilitate trade. It lacked vocabulary to translate spiritual concepts.

In 1840, Methodist missionaries Gustavus Hines and Jason Lee decided to visit the Umpqua in an attempt to bring Christianity to them. The Hudson’s Bay Company trader at Fort Umpqua, however, informed them of recent Indian attacks. He warned them not to visit the Umpqua villages. When the missionaries insisted, the trader and his Indian wife accompanied them. The trader later insisted that only the presence of his Indian wife kept them from being killed.

Like the Flathead in western Montana, the Coeur d’Alene in Idaho had heard about the powers of the Blackrobes from fur traders. In 1841, three Coeur d’Alene men traveled to western Montana to see the Jesuit missionary Father DeSmet. They asked him to send the Black Robes (Jesuits) to their people. The following year, the Jesuits sent Father Nicholas Point to establish a mission among the Coeur d’Alene. Jerry Camarillo Dunn, in his The Smithonian Guide to Historic America: The Rocky Mountain States, writes: “The mission had some success, although Father Point himself was dismayed by what he saw as his flock’s dirtiness, idolatry, and ‘moral abandonment.’”

In the nineteenth century there were several competing kinds of Christianity. The Protestant missionaries in Oregon Country resented the presence of Catholic missionaries whom they regarded as atheistic papists. In 1841, the wife of a Protestant missionary among the Nez Perce complained: “Romanism stalks abroad on our right hand and on our left and with daring effrontery boasts that she is to prevail and possess the land.”

Two years later, a Protestant missionary to the Nez Perce blamed his failure to convert Indians on the opposition of the Catholics.

In 1843, the Canadian missionary Father Bolduc established a mission among the Cowlitz in Washington. Bolduc wrote in his journal: “One must develop a strong spirit here. It is important to be kind to the savages, to make them laugh now and then so as not to frighten them, and give them a favorable impression of religion. It is not necessary to show them the severe side at first, but in time and successively to introduce everything, or the end will not be accomplished.” Bolduc also reported: “Since being with the Cowlitz tribe, I have converted only a few. They are unwilling to submit.”

According to Balduc, polygyny, slavery, and gambling were obstacles to conversion to Christianity.

In 1843, Father Nicholas Point and the Jesuit brother Charles Huet established a mission on the St. Joe River in Idaho to serve the Coeur d’Alene. Father Point noted that the Coeur d’Alene were living in 27 villages around Lake Coeur d’Alene.

In 1845, the Jesuits under Father De Smet established a mission at Chewelah, Washington. The mission was called Saint Francis Regis and was intended to serve the Kalispel as well mixed blood trappers who were living in the area.

While the Flathead had asked for a Blackrobe (Jesuit priest), what they were actually seeking was the spiritual power to enable them to defeat their traditional enemies, the Blackfoot who controlled much of the buffalo hunting grounds on the Northern Plains. After five years of living with them, Father De Smet had gained little real understanding of Flathead culture. Feeling that he had been successful in converting the Flathead, he crossed the Rocky Mountains and attempted to convert the Blackfoot. When he returned to the mission among the Flathead he found them angry with him and openly challenging his Christianity. Many of his converts left the church.

In 1846, the United States and the United Kingdom negotiated the Oregon Treaty which divided the territory between the two countries. Oregon Country thus became Oregon Territory.

Leave a Reply