In 1857, Enos Thomas, whose tribal identity is simply listed as Iroquois, was transported from Fort Vancouver to Port Orford, Oregon to be tried for war crimes committed during the recent Rogue River War. When the primary witness against him failed to appear, the Justice of the Peace William Copeland ordered the sheriff William Riley to free Enos. As soon as the blacksmith had freed him from his chains, a mob seized him, gave him some whiskey to drink, took him to the historic Battle Rock, and hung him. His body was buried at Battle Rock.

This type of incident—a mob hanging an Indian for “crimes” committed during a “war” with the United States—was common in the nineteenth century West. The interesting question is, however, how did an Iroquois, whose homelands are in the Northeast, come to be a war leader among tribes in southern Oregon?

The answer to this question lies in the early nineteenth century fur trade. The fur trade in the Pacific Northwest (in what would become Washington, Idaho, and Oregon) was dominated by two major fur companies: the London-based Hudson Bay Company (HBC) and the Montreal-based North West Company (the Nor’westers). As the Nor’westers moved into the area, they brought with them a number of Iroquois who were employed as trappers. These Iroquois had been educated by the Jesuits at the Caughnawaga Mission near Montreal in Canada. It was relatively common for these Iroquois to leave their employer and to settle among the tribes in the region.

The designation “Iroquois” does not refer to a single tribe, but is most frequently used to refer to the six Indian nations of the Iroquois Confederacy: Seneca, Cayuga, Mohawk, Onondaga, Oneida, and Tuscarora. The Iroquois homeland had originally included most of what is now New York and Ontario. Following the American Revolutionary War, many of the Iroquois settled in Canada.

Since many of the Iroquois who came to the Pacific Northwest spoke French as their primary European language, it was common for American settlers in the region to view them as French-Canadian. In most cases, the historic record does not indicate which of the Iroquois nations these trappers came from.

While there are no records regarding the early life of Enos (whose name is also indicated as Enas and Eneas and who is often described as a Canadian Indian), it is likely that he came into the region in the employ of HBC after the merger with the Nor’westers. He may also have grown up in a community of former HBC employees who had settled in Oregon. If this was the case, then his mother was most likely from an Oregon tribe or a Métis whose family was associated with the fur trade.

According to some historians, Enos may have worked as a guide for the 1843-1844 exploring expedition of John Charles Frémont: in 1843 Frémont hired two Indians—neither their names nor their tribal affiliations are recorded—to guide him from The Dalles to Klamath Lakes. According to Frémont’s records, one of these Indians had been to Klamath Lake and bore the battle scars of encounters with the Native people of that area. The physical description of this Indian appears to match that of Enos.

By 1855, Enos was living among the Tututni and had a Tututni wife. He was also friends with Benjamin Wright. In 1852, Wright had organized a party of volunteers in northern California for the purpose of killing Modocs. The Americans wanted to punish the Modoc for supposedly attacking wagon trains as they passed through Modoc territory. Wright then invited 46 Modocs to a peace conference. They first attempted to poison them with strychnine, but the Modoc declined the feast which was offered to them. The volunteers then opened fire with rifles on them. The Modoc had no guns. Only five of the Modoc, including Schonchin John and Curly Headed Doctor, escaped. The bodies of the dead Modoc were scalped and mutilated. The volunteers were proclaimed heroes and the state of California paid them for their services.

The following year, a group of Indians were invited into Wright’s camp under a white flag in order to negotiate peace. In a well-planned attack, Wright’s volunteers killed 38 Indians and scalped them.

In 1854, Benjamin Wright was appointed as special sub-Indian agent to handle affairs in the Port Orford, Oregon district. Enos and his wife gained Wright’s trust and he brought them into his confidence and sought their counsel.

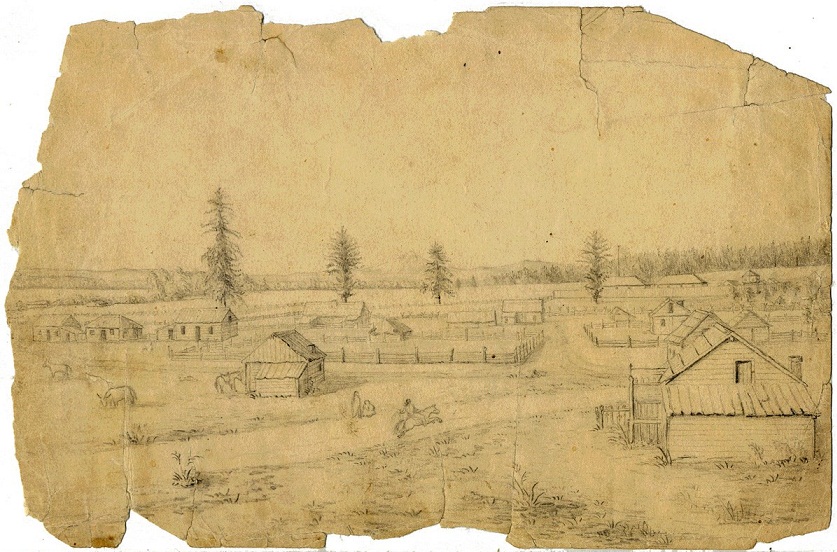

In 1855, the so-called Rogue River War broke out between the Americans (particularly gold miners) and the various Indian nations along Oregon’s Rogue River. In 1856, Enos asked Benjamin Wright to meet with him at the Tututni village to discuss a possible peace. Wright, together with John Poland who represented the mining communities in the area, went upstream to meet with Enos and the Tututni. Both men were then killed and their bodies mutilated. Their bodies were never found by the Americans. These murders were the first step in a well-planned Indian uprising. The following day, the Indians attacked a volunteer regiment on the north side of the Rogue River and then went downstream to attack the community of Gold Beach. Under the leadership of Enos, the Indians burned about 60 non-Indian cabins and killed 31 people. The Americans branded Enos as a war criminal.

The siege of Gold Beach lasted for about a month and the Americans easily recognized Enos riding a white horse and encouraging the Indians in their fight. When U.S. Army troops reached the area, the Indians retreated upstream. According to one account, Enos was wounded in the thigh at a skirmish at Pistol River.

In late July, 1856 (perhaps the 26th or 27th), Enos was at the camp of Tututni Chief Taminestse at Port Orford where the Indians were awaiting transportation to the Siletz Indian Reservation. Indian agent William Chance describes his arrest: “He made no resistance, said he could not keep away. He did not know why but it appeared to him that he had to come to the reservation.”

Among the Indian leaders of the Rogue River War, only Enos was arrested and singled out for trial. While Indian Superintendent Joel Palmer advocated the execution of all Indians who were known to have killed non-Indians during the war, only Enos was chosen for punishment. Enos was transferred from the coast reservation to Fort Vancouver where he was to be held awaiting a civil tribunal. The charges against him were murder and inciting to massacre.

In the spring of 1857, Enos was transported from Fort Vancouver to Port Orford by steamer. Due to bad weather, the ship had to dock to Crescent City to the south, when Enos was held in the local jail. When the weather cleared, he was taken north to Port Orford where he would be hung without a trial.

While it seemed to be important to the Americans to have a legal ritual (trial) before executing an Indian, in reality most Indians accused of crimes at this time were simply killed without this formality.

Leave a Reply