American Indians in 1890

The 1890 United States Census formally enumerated all of the Indians of the country. According to the Census, there were a total of 248,253 Indians in the United States: 58,806 are “Indians taxed” (that is living off their reservations) and 189,447 are “Indians not taxed” (Indians on reservations). With regard to the difficulties in counting Indians, the Census Bureau reports: “Enumeration would be likely to pass by many who had been identified all their lives with the localities where found, and who lived like the adjacent whites without any inquiry as to their race, entering them as native born white.”

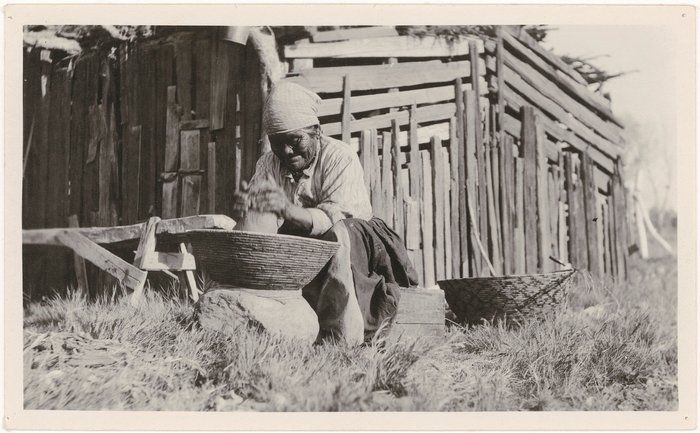

In California the Indian population was estimated at 15,238, down from an estimated 300,000 in 1848.

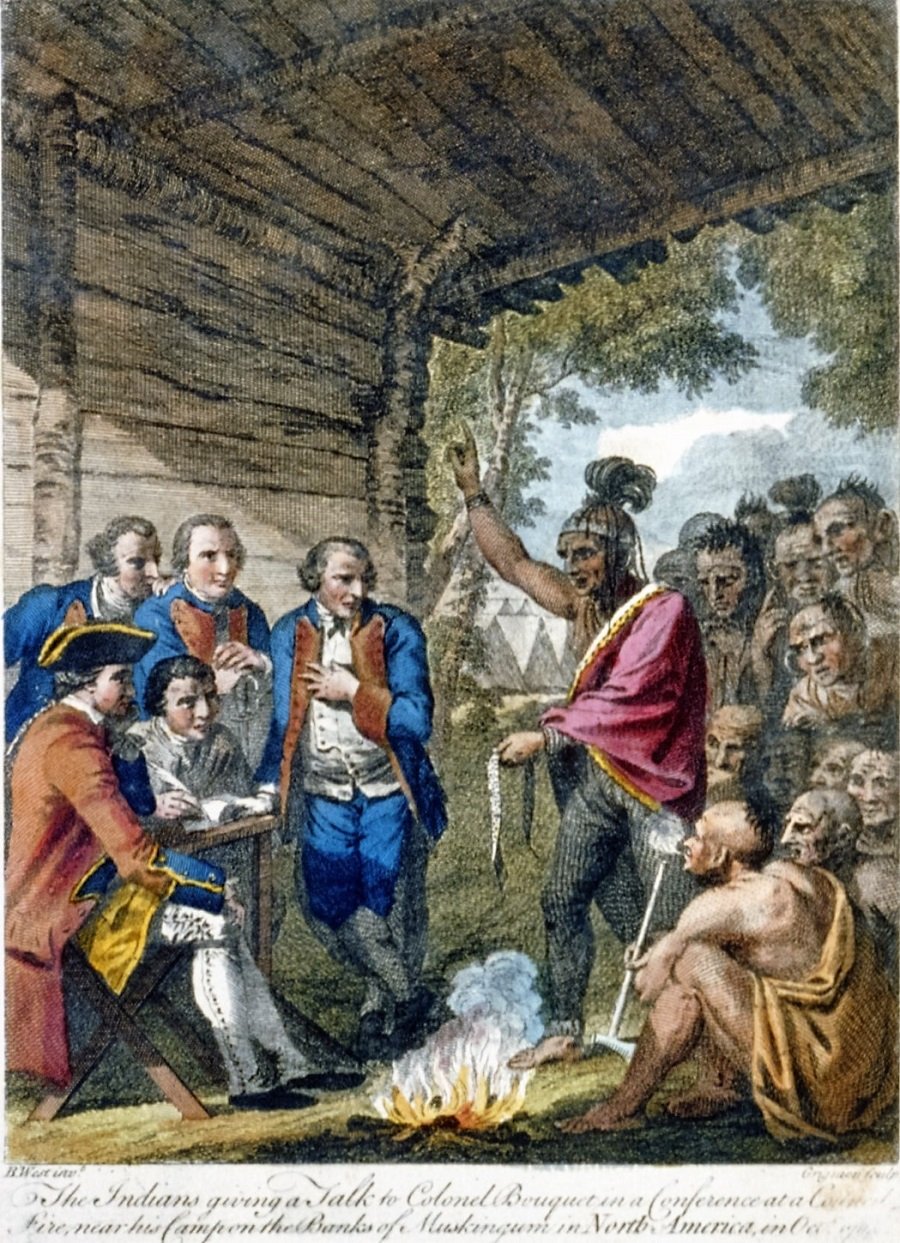

In 1890, most Indians were not citizens of the United States because Indian tribes, as indicated in the U.S. Constitution, were sovereign nations and Indians, therefore, were considered to be citizens of these Indian nations. In an effort to make more Indians citizens, Congress passed the Indian Territory Naturalization Act which allowed any member of an Indian tribe in Indian Territory (what is now Oklahoma) to become a United States citizen by applying for such status in federal courts. The act allowed these Indians to maintain dual citizenship by maintaining tribal citizenship. Few Indians, however, actually applied for U.S. citizenship under this legislation.

The Commissioner of Indian Affairs announced that the 8th of February was to be celebrated by American Indians as Franchise Day. It was on this day that the General Allotment Act (also known as the Dawes Act) was signed into law. The purpose of this legislation was to break up the reservations into small family farms and to open up “surplus” lands to non-Indian settlement. The Commissioner felt that this legislation– “is worthy of being observed in all Indian schools as the possible turning point in Indian history, the point at which the Indians may strike out from tribal and reservation life and enter American citizenship and nationality.”

The Commissioner of Indian Affairs published a detailed set of rules for Indian schools which stipulated a uniform course of study and the textbooks which were to be used in the schools. The Commissioner prescribed the celebration of United States national holidays as a way of replacing Indian heroes and assimilating Indians. According to the Commissioner: “Education should seek the disintegration of the tribes, and not their segregation. They should be educated, not as Indians, but as Americans.”

Schools were to give Indian students surnames so that as they become property owners it would be easier to fix lines of inheritance. Since most teachers could not pronounce or memorize names in native languages, and they did not understand these names when translated into English, it was not uncommon to give English surnames as well as English first names to the students. Many Indian students were given names such as “George Washington,” “William Shakespeare,” and “Thomas Jefferson.” On the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming, the Indian agent reported that: “Now every family has a name. Every father, mother; every husband and wife and children bears the last names of these people; now property goes to his descendant.”

In noting that Indians often change names in response to events in their lives, Frank Terry, the Superintendent of the Crow Boarding School in Montana, wrote: “Hence it will be seen that the Indian names are nothing, a delusion, and a snare, and the practice of converting them into English appears eminently unwise.”

While it was government policy to force American-style education and indoctrination upon Indian children, Indian parents on many reservations resisted. To force compliance, rations were withheld from Cheyenne and Arapaho parents who refused to place their children in school. In California, Indians burned the Indian day school at Tule River.

In Arizona, conservatives in the Hopi village of Oraibi refused to send their children to school. The Tenth Cavalry was sent in to ensure peace. The military troops invaded the village and “captured” 104 children for the school.

In Idaho, the Indian agent for the Fort Hall reservation managed to enroll 100 Shoshone and Bannock children in the agency boarding school. With the use of Indian police and a policy of withholding rations from reluctant parents, nearly half of all of the school-aged children on the reservation were enrolled in the school. When enrollment at the school dropped, a council was held with the Shoshone and Bannock and they were informed that the school was to be kept filled or the soldiers would come.

Taking a moralist approach to the “civilizing” of American Indians, many non-Indians felt that Indians needed to understand the meaning of hard work and sacrifice. Things that might bring some semblance of enjoyment, such as gambling, drinking, and singing traditional songs, was felt to be immoral. Thus the Commissioner of Indian Affairs ordered traders to stop carrying playing cards. This was one of the government’s efforts to discourage gambling on the reservations. In a related action, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs ordered Indian agents to seize and destroy peyote and to classify it as an intoxicating liquor.

Many non-Indians felt that it would take time for Indians to be lifted out of savagery and barbarism so that they could benefit from Christian civilization. Reverend Daniel Dorchester, a Protestant minister, wrote to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs: “As a race the red men lack self-reliance and self-directing power—the natural effect of the centuries of ignorance, idleness, and hap-hazard lying behind them—and will long need to hold the relation of wards, that they may have the benefit of paternal counsel and advice. We must not expect that a few Indians right out of savagery can acquire such development in civilization as to leaven at once the mass of barbarism.”