Long before the Europeans arrived on this continent there was born to the Huron people a man who had a vision of bringing peace to his people. In his vision he saw a great pine tree. The roots of this tree were five powerful nations. From these roots, the tree grew so high that its tip pierced through the sky and on top there was an eagle watching to see that none of the nations broke the peace among them. This Peacemaker was a man named Deganawida (also spelled Deganawidah).

According to oral tradition, Deganawida named each of the allied nations, choosing a place as the distinguishing feature of nationality:

- Seneca: the big hill people, or the people of the big mountain

- Cayuga: the people at the landing, in reference to portaging a canoe

- Mohawk: the people of the flint, in reference to the flint quarries in their territory

- Onondaga: the people of the hill, in reference to the hill where a woman long ago had appeared to give the people corn, beans, squash, and tobacco

- Oneida: the people of the standing stone, in reference to the supernatural stone which followed them

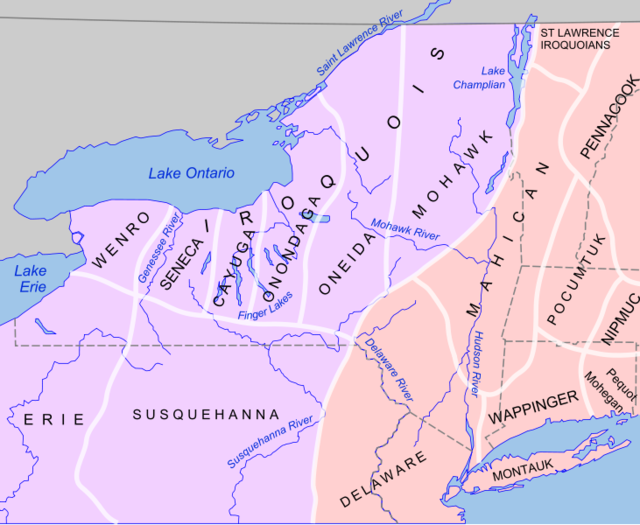

Deganawida’s vision, articulated through the great Mohawk orator Hiawatha, united five Iroquois-speaking nations – the Seneca, the Cayuga, the Onondaga, the Oneida, and the Mohawk– into the League of Five Nations. Later the Tuscarora would join them to form the League of Six Nations. The League is also called the Iroquois Confederacy. They refer to themselves as Haudenosaunee (People of the Longhouse).

With regard to the Great Law which established the Confederacy, Kevin White, in an article in Indian Country Today, writes:

“The core concepts of the Great Law of the Haudenosaunee are peace, power, and righteousness.”

Former Commissioner of Indian Affairs John Collier, in his book Indians of the Americas, writes:

“The plan was to renounce warfare between one another and to present an alliance against a warring world.”

He also calls the League of Five Nations “the most brilliant creation in the record of man.” The Haudenosaunee put it this way:

“The Haudenosaunee, or Six Nations Iroquois Confederacy, is among the most ancient continuously operating governments in the world. Long before the arrival of the European peoples in North America, our people met in council to enact the principles of peaceful coexistence among nations and in recognition of the right of peoples to continue an uninterrupted existence.”

These principles include kinship, women’s leadership, and the widest possible community consensus.

The story of Deganawida and the founding of the League is a story of epic proportions which continues to be recounted in the oral traditions of the Iroquois today. According to anthropologist William Fenton, in his chapter in North American Indians in Historical Perspective:

“A knowledge of the teaching imputed to Deganawidah goes far to explain Iroquois self-confidence, their superiority to their neighbors, and at times their polite arrogance to the representatives of European governments.”

While the designation “Iroquois” is often used to refer to the Five or Six Nations, it should be remembered that not all Iroquois-speaking nations in the Northeast were members of the League. Deganawida’s own nation – the Huron – did not join.

The League of Five Nations originally had 50 permanent offices filled from the member nations: 14 from the Onondaga, 10 from the Cayuga, 9 from the Oneida, 9 from the Mohawk, and 8 from the Seneca. The men who filled these offices are known as sachems. According to former Commissioner of Indian Affairs John Collier:

“The Confederacy was one of delegated, limited powers; and with exhaustive care and success, it was so structured that authority flowed upward, from the smallest and most organic units, not downward from the top.”

He goes on to say:

“The Confederacy was a nation which enhanced the liberty and responsibility of its component parts down even to the minutest member.”

It was the women who first accepted the message of Deganawida, the prophet who first envisioned the League. Therefore, the women have a great deal of authority. The sachems are selected by the clan mothers. Women also have the right to initiative, recall, and referendum.

With regard to Iroquois leadership, Onondaga chief Oren Lyons, in Voice of Indigenous Peoples: Native People Address the United Nations, says:

“Our leaders were instructed to be men with vision and to make every decision on behalf of the seventh generation to come, to have compassion and love for those generations yet unborn.”

Deganawida, the Peacemaker and Founder of the League of Five Nations, is said to have advised the sachems that their “skin should be seven thumbs thick so that no outrageous criticism or evil magic could pierce them.”

There are three great double doctrines or principles (six principles in all) upon which the League was founded. The first principle stresses: (a) health of mind and body, and (b) peace among individuals and groups. The second principle stresses: (a) righteousness in conduct, including advocating this righteousness in thought and speech, and (b) equality in the adjustment of rights and obligations. The third principle stresses: (a) physical strength, power, and order, and (b) spiritual power (orenda).

Traditionally at the meetings of the League, each of the delegates from the Five Nations sat at assigned places in accordance with their position in the confederacy. As firekeepers, the Onondaga would give the topic for discussion first to the Mohawk and Seneca. The Mohawk would then discuss the matter among themselves and then refer it to the Seneca. After discussing the issue, the Seneca would return the item to the Mohawk who would hand the item across the fire to the Younger Brothers. It would then be discussed by the Oneida and then by the Cayuga. The Oneida would then hand it back across the fire to the Mohawk who would announce the combined opinion to the Onondaga. In her chapter “The League of the Iroquois: Its History, Politics, and Ritual,” in the Handbook of North American Indians Elizabeth Tooker reports:

“If the Onondaga disagreed, they referred it back for further discussion, but in so doing they had to show that the opinion of the other tribes was in conflict with the established custom or with public policy.”

While speaking, the speaker would hold a wampum belt which would then be handed to the tribe being addressed. In his book The Divided Ground: Indians, Settlers, and the Northern Borderland of the American Revolution, historian Alan Taylor reports:

“As a sacred substance, wampum confirmed the earnest importance of a message. Without accompanying wampum, words were frivolous.”

Traditionally, an issue would be introduced at the council on one day, but not discussed that day. At some later time it would be discussed. It is tradition that the issue be slept with prior to discussing. Anthropologist William Fenton puts it this way:

“No Iroquois to this day will answer to a proposition on the same day, nor will he press another party for a reply until the latter is ready. One listens carefully, repeats the main points of what he hears, and then takes the message home and puts it under his head for the night as a pillow.”

Speeches at the council were made by individuals who were not only well-versed in proper Iroquois protocol, but also articulate orators. Historian José António Brandão, in his book “Your Fyre Shall Burn No More” Iroquois Policy toward New France and Its Native Allies to 1701, writes:

“They could be subtle and evasive enough to give an answer that the other side wished to hear, but without actually committing their tribes to a specific course of action.”

One important Iroquois custom was documenting their words with wampum belts. All agreements, for example, were accompanied by wampum belts which symbolized the important points of the agreement. At later times, the belts would be brought out and “read” if the agreement needed to be discussed again.

In order to record what was said in council, the Sachem presiding over the meeting would have a handful of small sticks. A stick would be given to one of the Sachems present so that the person with the stick would be responsible for remembering what the speaker said.

Historian José António Brandão summarizes the governing power of the Iroquois Confederacy during the 17th century:

“The Iroquois had no permanent governing body constantly in session and directing policy. What they had instead was a framework that allowed for joint action when the member tribes felt the need for it.”

Anthropologist William Fenton describes the League this way:

“What made the League effective was not its ability to centralize power and communicate authority to the margins, in which it failed miserably, but the consensus not to feud among the Five Nations and to compound such infractions by ritual payments of wampum.”

Among the nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, there were two hereditary war chiefs and both of these titles belonged to the Seneca. They were Needle Breaker who belonged to the Wolf clan and Great Oyster Shell of the Turtle clan. The Seneca, as Guardians of the Western Door, were the first of the Iroquois to face the danger of an attack on the western frontier. These two chiefs assumed the planning for the military operations of the Five Nations.

The League of Five Nations also had Pine Tree Chiefs who served as advisors to the sachems. The Pine Tree Chiefs were outstanding orators, war leaders, and others who did not hold hereditary offices. Anthropologist William Fenton writes:

“Pine Tree chiefs were orators for the council or they spoke for the women, and they went on embassies.”

Within the League, the tribes are divided into two sides or moieties. In council, the Mohawk, Onondaga, and Seneca are considered “brothers” to each other and as “fathers” to the younger tribes (Oneida, Cayuga, Tuscarora). The Cayuga call the Oneida “elder brothers” and they call the Tuscarora “younger brothers”.

The members of the League of Five Nations made a distinction between civil chiefs and war chiefs. However, more prestige was given to the civil chiefs. The civil chiefs were viewed as fire keepers in the center of a concentric ring of warriors, women, and the general public.

Another important position in the Iroquois political system was the runner. In noting the importance of this position, historian Laurence Hauptman and former Oneida tribal secretary Gordon McLester, in their biography Chief Daniel Bread and the Oneida Nation of Indians of Wisconsin, write:

“Iroquois runners summoned councils, conveyed intelligence from nation to nation, and warned of impending danger. It is also important to note that the Iroquois use the term runner to describe a person who serves the council as a conduit for the conduct of essential business, and who is accorded respect as a community leader worthy of other higher positions of authority and prestige in the nation.”

The League of Five Nations Council traditionally met in the later summer or early fall at the council fires of the Onondaga.

Leave a Reply