Very soon after the Spanish began their invasion of this continent, both the European courts and clergy declared Indians to be “people” in a biological and spiritual sense. However, the concept of Indians as “people” in a legal sense was tested in the United States in 1879.

In 1877, the United States had forcibly removed the Ponca from their homeland in northern Nebraska and resettled far to the south in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). One-third of the tribe died from starvation and disease shortly after their arrival on the new reservation.

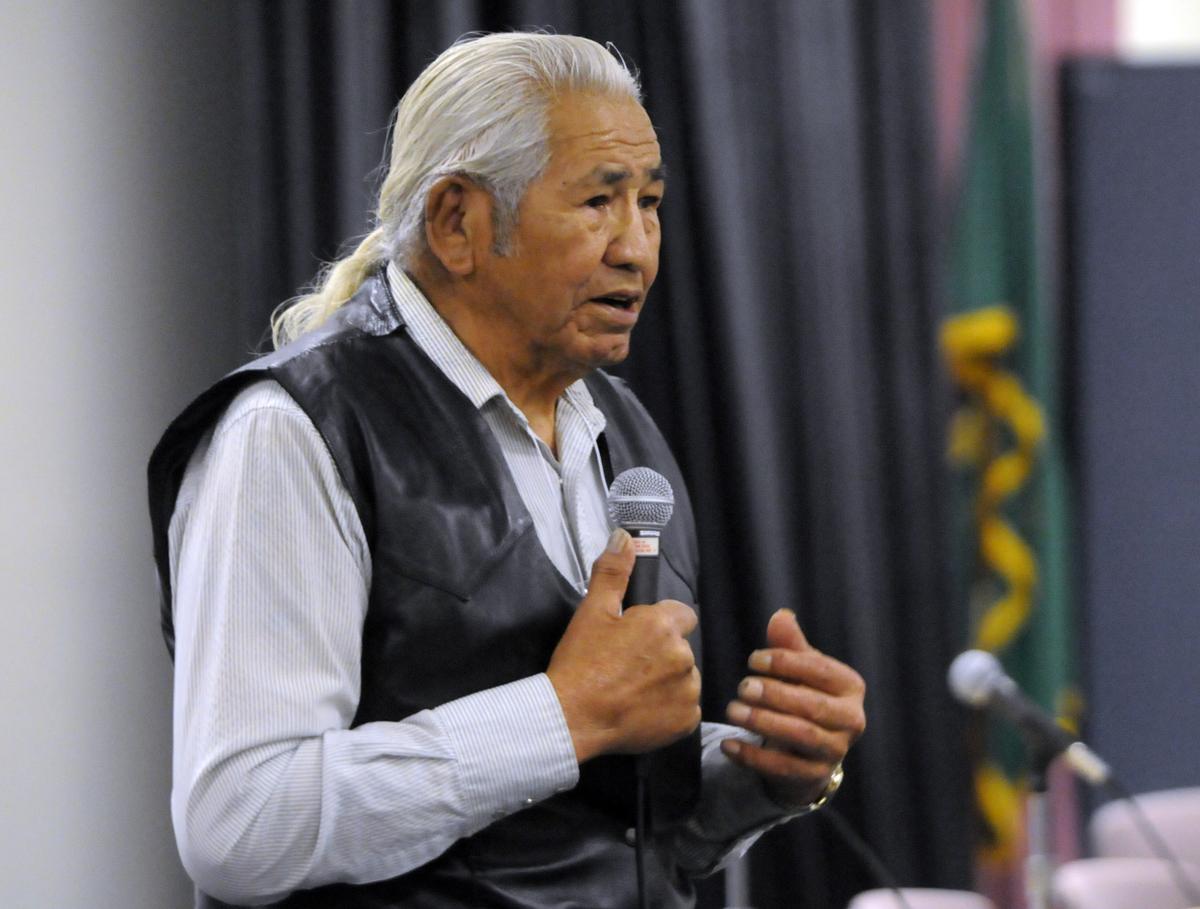

In 1879, Standing Bear and about 30 Ponca left their Oklahoma reservation and traveled to Decatur, Nebraska where they were welcomed by the Omaha (the tribe, not the city) and given food and shelter. Standing Bear explained why he left Oklahoma:

“My boy who died down there, as he was dying looked up to me and said, I would like you take my bones back and bury them where I was born. I promised him I would. I could not refuse the dying request of my boy. I have attempted to keep my word. His bones are in that trunk.”

At this time, Indians were not allowed free movement outside of their reservations. In order to leave the reservation they were required to have the written permission of their Indian agent. The Department of the Interior (the federal agency in charge of Indian affairs) notified the War Department that the Ponca had left without permission and the army was ordered to return them to the reservation. The Ponca were then detained by the army under the command of General George Crook at Fort Omaha. Illness among the Indians and the poor condition of their horses made it impossible to return them to Oklahoma immediately. During the delay, a local newspaper story about the plight of the Ponca stirred up interest and support which resulted in an historic court case. Carl Waldman, in his book Who Was Who in Native American History, writes:

“When the true purpose of Standing Bear’s journey was published, some whites, including Crook himself, showed sympathy.”

In an interview with newspaper editor Thomas Henry Tibbles, Ta-zha-but (Buffalo Chip) asked:

“I have done no wrong, and yet I am here a prisoner. Have you a law for white men, and a different law for those who are not white?”

In defending the arrest of Standing Bear’s people, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs wrote:

“If the reservation system is to be maintained, discontented and restless or mischievous Indians cannot be permitted to leave their reservation at will and go where they please. If this were permitted the most necessary discipline of the reservations would soon be entirely broken up, all authority over the Indians would cease, and in a short time the Western country would swarm with roving and lawless bands of Indians, spreading a spirit of uneasiness and restlessness even among those Indians who are now at work and doing well.”

Under American law, everyone, including non-citizens, who is held by U.S. authorities has the right to challenge the legality of the custody through a writ of habeas corpus. Two attorneys, John Webster and Andrew Poppleton, volunteered their services to the captive Poncas and filed a writ of habeas corpus to free them from Army custody. The U.S. Attorney argued that Indians were not persons under the law and therefore were not entitled to a writ of habeas corpus. According to the government an Indian was neither a person nor a citizen within the meaning of the law, and therefore could bring no suit of any kind against the government.

After hearing the case of Standing Bear v Crook, the United States District Court found that if Indians must obey the laws of the land, then they must be afforded the protection of these laws. In other words, Indians are “people” under United States law and therefore have the right to sue for a writ of habeas corpus. The judge observed:

“On the one side, we have a few of the remnants of a once numerous and powerful, but now weak, insignificant, unlettered and generally despised race. On the other, we have the representatives of one of the most powerful, most enlightened, and most Christianized nations of modern times.”

The Court’s ruling ordered Crook to release Standing Bear and his people.

The Commissioner of Indian Affairs responded to the judge’s ruling by noting that it–

“is regarded by the Government as a heavy blow to the present Indian system, that, if sustained, will prove extremely dangerous alike to whites and Indians.”

Not all Americans agreed with the Court’s decision. One writer in New York City, asked of the Ponca: “What right have they to be in the country, anyhow?” The writer goes on to say:

“They are nothing but barbarians; they have no vote; while we are Christians and voters. Therefore, the land they occupy is unprofitable, and I for one cannot see why any white man who is a voter, and desires the land, should not make a claim to it, and if necessary, get help from the Government to obtain it.”

In theory, this ruling should have changed the legal relationships for Indian people on reservations throughout the United States. However, it was almost universally ignored by the Indian Service (later known as the Bureau of Indian Affairs), Indian agents (the people in charge of the reservations), the army, and the local courts. The ruling was not appealed as it was felt that it would probably be upheld by the Supreme Court and this would only give it more weight in American law.

With regard to the Standing Bear case, in his book In the Courts of the Conqueror: The 10 Worst Indian Law Cases Ever Decided, attorney Walter Echo-Hawk writes:

“This decision opened Indian eyes to the possibility of protecting their rights through litigation.”

Following the Standing Bear versus Crook decision, newspaper editor Henry Tibbles arranged a six-month lecture tour of eastern cities for Standing Bear. When Standing Bear traveled, he would wear European-style clothing. On stage, however, he would wear buckskins, feathers, beaded belt, claw necklace, and red blanket. In Boston, Standing Bear’s lecture was attended by Helen Hunt Jackson, Senator Henry Dawes, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and other notables who were so moved that they formed the Boston Indian Citizenship Committee to fight for the rights of the Ponca and other Indians.

In 1880, Congress appointed a committee to study the Ponca situation. As a result, Standing Bear and his small band were given a permanent home in Nebraska.

Leave a Reply