The 17th Century Wampanoag

( – promoted by navajo)

In 1600, shortly before the beginning of the European invasion, the population of the Wampanoag people in Massachusetts was estimated at 12,000 living in 40 villages. Two years later, Bartholomew Gosnold landed at Cape Cod and traded with the Wampanoag. He reported that the Indians were in good health. When he returned to England he promoted the establishment of colonies in the area.

In 1603, the English under the leadership of Martin Pring, built a palisaded trading camp at Cape Cod in Wampanoag territory. While the English entertained the Wampanoag with small gifts and guitar music, they also stole a large birchbark canoe. Consequently, the relations between the English and the Indians deteriorated and the English fired their muskets and loosed mastiffs at Wampanoag warriors before abandoning the fort.

Three years later French explorers attempted to impress the Wampanoag in the village of Monomoy with their guns and swords. The French erected a large cross as a symbol of Christian domination and claim to the land. The Wampanoag response was to kill four of the landing party, tear down the cross, and jeer at the retreating French.

In 1614, English Captain Thomas Hunt captured 26 Wampanoag, including a young man known as Squanto. The Indians were taken to Spain and sold as slaves. However, Squanto escaped and found his way to England where he learned to speak English.

John Smith, the former commander at Jamestown, led two ships in search of gold and whales along the coast of Maine in 1614. After some fishing, trading, and skirmishes with the natives, the English captured 27 Wampanoag and Nauset to sell into slavery.

While mapping the New England coast, Smith noted at least nine coastal towns between Cape Ann and Cape Code, each of which was ruled by a sachem. In addition, he reported that that there were more than 20 towns inland from the coast.

About 1614, a series of three epidemics, inadvertently introduced through contact with Europeans, began to sweep through the Indian villages in Massachusetts. At least ten Wampanoag villages were abandoned because there were no survivors. The Wampanoag population decreased from 12,000 to 5,000.

Note: It is not known what the actual disease was that caused this epidemic. Various writers have suggested bubonic plague, smallpox, and hepatitis A. There is strong evidence supporting all of these theories. It is estimated that by 1619, 75% of the Native population of New England had died as a result of this epidemic.

When Squanto returned from England with captain Thomas Dermer in 1619, he searched for the Wampanoag of his village, but found that they had all died in the epidemic.

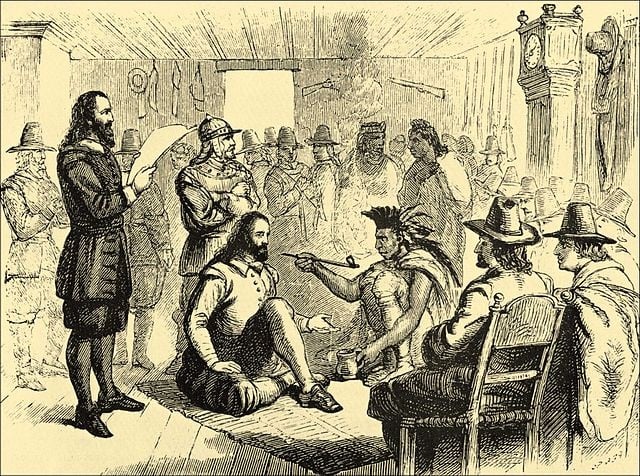

In 1621, Massasoit, leader of the Wampanoag, established formal diplomatic relations with the newly arrived Pilgrims and both sides pledged mutual support and protection. With this treaty, Massasoit bolstered his economic, political, and military control over the region. He assumed that the treaty made the Pilgrims members of his confederation. As a sign of good faith, Massasoit assigned Squanto to live with the colonists and to serve as a liaison between the two groups.

The Wampanoag leader Massasoit died in 1660. The peace which he had helped forge with the Europeans began to crumble. Massasoit had insisted “The Puritans are our friends.” His son, Wamsutta, assumed leadership and proved to be less yielding to English demands.

Two years later, Wamsutta (also known as Alexander) was ordered to Plymouth to meet with the English governor and to discuss the rumors that he was planning war. The meeting was cut short as Wamsutta became ill. He died before he could return home. The Indians claimed that Wamsutta was poisoned by the English. His brother Metacom would later say:

“My brother came miserably to die, by being forced to Court and poisoned.”

With the death of Wamsutta, his younger brother Metacom (known to the English as Philip or King Philip) assumed the duties of principal sachem. Metacom managed to calm the warriors who were calling for war to avenge Wamsutta’s death. One of his first official acts as Wampanoag leader was to tell the English that he wanted to stop selling land for seven years.

The English colonists were not pleased with Metacom’s decision not to sell land. Five years later, they simply ignored Wampanoag land ownership and established the town of Swansea, just four miles from Metacom’s village.

In 1671, the English colonial government, having been informed by Christian Indians that Metacom was enlisting other tribes to resist further English expansion, invited him to a council. Metacom listened to the English accusations, signed an agreement to give up all Wampanoag firearms, promised to pay a tribute of 100 pounds per year, and left before dinner. It is not known if the English understood that not sharing a meal was an insult. The Wampanoag guns were not surrendered.

In 1675, pushed by the Puritans who demanded that the Indians obey Puritan law and who severely punished the Indians who did not, Metacom asserted the sovereignty of his people by going to war. As a result of this war – commonly called King Philip’s War – many of the smaller Indian nations were destroyed or scattered. Metacom attempted to create a pan-Indian alliance to halt English expansion.

The prelude to the war was a murder trial. A converted Christian Indian named John Sassamon had told the English governor that Metacom was plotting against the English and that he feared for his life. A short while later, Sassamon was found dead beneath the ice of Assawompsett Pond. The Puritans felt that Sassamon was murdered because he was a spy for the Puritans. Sassamon had served as Philip’s secretary. Three Wampanoag men-Tobias (one of Philip’s counselors), Wampapaquan (Tobias’ son), and Mattashunnamo (a warrior)-were tried by the Puritans, found guilty, and hanged. The execution of these three men stirred many Wampanoag to violence against the Europeans.

Metacom evaded capture by basing his raids in the Pocasset territory of the female sachem Weetamoo. From here he carried out successful raids against five English towns. Humiliated by these defeats, the English Christian ministers concluded that God was unhappy with them because of the wearing of wigs and the tolerance shown to the Quakers.

Metacom’s strategy was to fight the English rather than submit to their ways. However, the Indians fought the war with little planning: Indian war was traditionally based on small, fast raids. While the English envisioned Metacom as the commander of a large intertribal force, there were probably no more than 300 warriors involved, most of whom were Wampanoag. By 1675, the Wampanoag population had decreased to about 1,000.

The following year, English forces attacked the camp of Watamoo, Metacom’s sister-in-law, in present-day Connecticut. She drowned while trying to escape and the English cut off her head and displayed it in their towns.

The English also captured King Philip’s wife, Wootonekanuske, and his nine year old son. They were held in a prison in Plymouth. The Puritan clergy debated the fate of Philip’s son: many felt that he should be executed, but others felt that the Bible says that no one should be executed for the sins of their fathers. After much debate, the boy was sold into slavery instead of being executed. The Puritan ministers felt that slavery was a compassionate compromise. They felt that notorious Indians, like Metacom himself, were to be executed; harmless enemies, mainly women and young children, were to be forced into servitude for a period of years; and those who were neither notorious enough to be hanged nor harmless enough to remain in New England were routinely sold into foreign slavery.

Metacom, on the run since the defeat of his people by the English, returned to his father’s old capital at Montaup and stumbled into an ambush in which he was shot and killed. The English drew and quartered his body and took his head to Plymouth where it was displayed to the public for 20 years. The Christian preacher Cotton Mather recalls that his

“Head was carried in triumph to Plymouth, where it arrived on the very Day that the Church there was keeping a Solemn Thanksgiving to God. God sent ’em in the Head of a Leviathan for a Thanksgiving-Feast.”

By the end of the war, the Wampanoag were nearly exterminated: only 400 survived.