During the nineteenth century, academics, politicians, teachers, historians, and the general public knew that Americans Indians were a vanishing race, destined to disappear before the relentless superiority of American manifest destiny, greed, private property, and capitalism. More than a decade into the twentieth century, however, American Indians continued to exist and Indian reservations were generally places of great poverty. The nineteenth century policies regarding the administration of Indian affairs continued, and seemed to be more determined than ever to make sure that Indians would disappear. During the twentieth century, many historians and others, believing in the myth of American superiority, actually believed that Indians had disappeared and thus twentieth century Indians are usually invisible in the histories of this century. Looking back to a century ago, to the year 1912, we see that there is, however, an Indian history for this year.

Commissioner of Indian Affairs:

The Commissioner of Indian Affairs in the Department of the Interior is the person responsible for administering Indian programs and policies. This is a political appointment.

Indian Commissioner Robert Valentine issued Circular 601 which prohibited teachers in government schools from wearing religious garb or displaying religious insignia. The order directly affected fifty-one people, mostly Catholic nuns. It was a part of the ongoing antagonism between Protestants and Catholics at this time. President William Howard Taft, however, revoked the Circular and ordered Valentine not to take any further action in this matter. Taft’s actions were criticized by Protestant groups and lauded by Catholics.

The Commissioner of Indian Affairs asked Indian superintendents to tell him about the effects of fee patents on the Indians on their reservations. With regard to the Omaha, 90% of those who had been issued fee patents by the competency commission had already sold their land, 8% had mortgaged their land, and only 2% still retained their allotments. In other words, the intent of allotment to turn Indians into farmers wasn’t working and was instead resulting in poverty.

To speed up the allotment of Indian land, experimental competency commissions were established by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs for the Umatilla and Omaha reservations. The commissions studied individual cases and passed judgments on the competency of individual Indians to handle their own affairs.

The new Commissioner of Indian Affairs Cato Sells directed Indian agents to confiscate individually owned cattle and to form tribal herds on the Northern Plains reservations. He felt that greater growth and profit could be realized if the herds were under the management of the Indian Office (later known as the Bureau of Indian Affairs). In Montana, the Northern Cheyenne attempted to resist the confiscation order as individually owned cattle were now not only a means of subsistence, but also a source of prestige. The Indian agent threatened lengthy jail terms for anyone who failed to comply with the confiscation order.

Court Cases:

In Choate versus Trapp the U.S. Supreme Court did not allow the state of Oklahoma to tax Choctaw and Chickasaw allotments.

The United States Court of Claims awarded the descendants of the Cathlamet in Oregon $7,000 for loss of their aboriginal lands.

Congress:

In Washington, D.C., representatives from the Four Mothers Society from the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, and Chickasaw tribes in Oklahoma testified in Congress against the allotment of tribal lands to individual tribal members.

Congress passed an act to provide for the sale of unallotted land on the Omaha reservation in Nebraska. Proceeds from the sale were to be deposited into the U.S. Treasury and to be distributed to eligible Omaha children when they turned 25. Under the act, 49 acres were to be reserved for the Indian agency, 10 acres for an Indian cemetery, and 10 acres for the Presbyterian church. An additional two acres of the old Presbyterian mission were to be deeded to the Nebraska State Historical Society.

Congress awarded the Chinook $20,000 for loss of their aboriginal lands in Washington. Congress also awarded the Clatsop $16,500 and the Wahkiakum $7,000 to satisfy land claims from their unratified 1851 treaty.

Legislation was introduced in Congress which would free the Apache at Fort Sill in Oklahoma from their prisoner of war status and relocate them on the Mescalero Apache reservation in New Mexico. The legislation was opposed by the New Mexico delegation as they wished to preserve non-Indian grazing rights on the Mescalero Reservation.

Shown above is Geronimo’s Grave at Fort Sill.

Presidential Executive Orders:

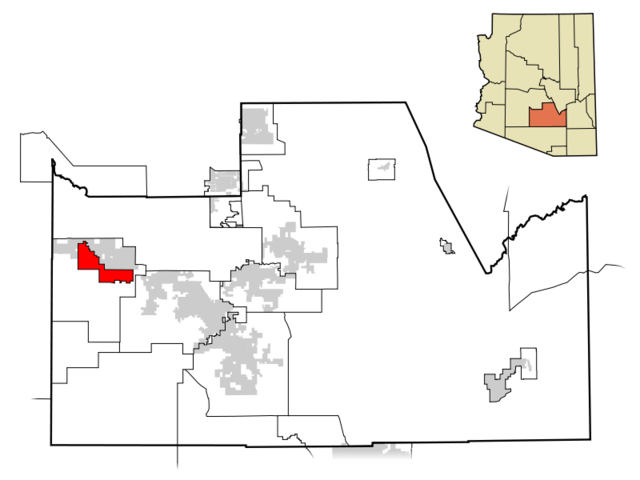

President William Howard Taft issued an executive order creating the 47,600 acre Ak-Chin reservation in Arizona. The reservation was created in part in gratitude to the Papago (Tohono O’odham) for their help in the wars against the Apache in the late 1800’s. In addition to Ak-Chin, a series of Executive Orders created the Maricopa, Cockleburr, Chi Chisch, Tat-muri-ma-kutt, and Boboquivari Peak-Santiergos Reservations for the Papago.

Shown above is a map showing the location of the Ak-Chin Reservation.

In Utah, President William Howard Taft used a Presidential Executive Order to set aside 80 acres in Skull Valley for the exclusive use of the Gosiute.

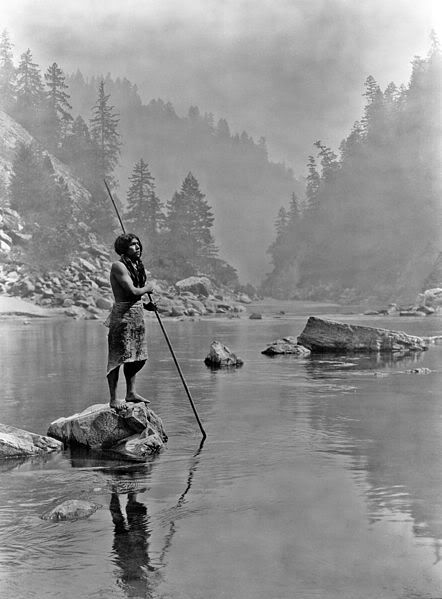

In California, the Hupa Reservation was restored by President Taft to its status prior to the 1908 proclamation by President Theodore Roosevelt which gave most of the reservation to the Trinity National Forest. The Hupa recovered their lands, but many people, including at least one reservation superintendent, assumed that part of the reservation belonged to the forest service which administered it.

Shown above is a photograph of the Hupa Reservation by Edward Curtis.

Suppressing Indian Religions:

The Board of Indian Commissioners began to lobby Congress for a law to outlaw peyote. According to their annual report:

“The danger of the rapid spread of the habit, increased by its so-called religious associations, makes the need of its early suppression doubly pressing.”

Delegations from several tribes – Omaha, Cheyenne, and Arapaho – visited Washington to express their opposition to attempts to outlaw peyote. The Commissioner of Indian Affairs, however, told Congress:

“I firmly believe that the use of Peyote is injurious to the health and welfare of the Indians and, therefore, shall do everything within my power to prevent its use among Indians”

The director of the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions sent the Bureau of Indian Affairs a request to rid the reservations of the evils of mescal. The director confused mescal with peyote.

In South Dakota, the Indian agent for the Yankton Sioux imprisoned the leaders of the Native American Church (which uses peyote in ceremonies). No court trial was felt necessary for this.

Allotments:

From an Indian viewpoint, non-Indians seemed to be obsessed with the idea of private property and were offended by the fact that Indian nations tended to own land communally. In the late nineteenth century, the United States passed laws to break up the communal ownership of Indian lands and to require the Indians to have allotments-individually owned parcels of land, generally too small to be economically viable as agricultural land. This focus on allotment continued in 1912.

In Minnesota, the investigation of fraud on the Chippewa White Earth Reservation resulted in 1,529 cases of illegally sold trust allotments being sent to the Department of Justice. Lumber interests and their political allies met to discuss the investigation. As a result of this meeting, they urged Congress to create a roll commission to fix the blood quantum of the White Earth allottees more accurately. This delayed the adjudication of the cases.

In Oklahoma, nearly 2,000 Cherokee refused to claim their allotments. Most of these traditional Cherokee were living in the hills in extreme poverty. In spite of this poverty, they refused the per capita payments which they would receive by taking an allotment.

In Nevada, a delegation of 30 Mason Valley Paiute under the leadership of Jack Wilson (Wovoka) requested 40-acre farm allotments from the Indian agent at the Walker River Reservation.

In Nevada, the Indian Office appointed a special agent for all off-reservation Indians in Nevada and Northern California. The special agent encouraged Indians to file for individual Indian allotments under Section 4 of the 1887 General Allotment Act.

In California, the Fort Yuma Reservation was allotted.

In Montana, 2,750 allotments were issued on the Blackfeet Reservation.

Landless Indians:

There were many Indian tribes in the twentieth century which did not have reservations. Some of these, such as the Chippewa and Cree, were refugees from Canada where they had participated in the nineteenth century Riel Rebellion in Saskatchewan. Others, such as Little Shell’s band of Chippewa, had had their reservation taken from them by land-hungry Americans.

In Montana, Fred A. Baker, a superintendent of Indian Schools, was assigned the task of finding lands for the landless Chippewa and Cree. Like most non-Indians at this time, Baker strongly believed that the assimilation of American Indians could best be achieved by making them into rural farmers. There was no concern for integrating them into the urban, market-based economy that was the reality for most Americans.

Baker held a council with Chippewa leader Stone Child (Rocky Boy), Cree leader Little Bear, and others at the Independence Day Celebration on the Blackfeet Reservation. He then held a separate meeting with Blackfeet leaders. While Baker had hoped that the Chippewa and Cree could be settled on the Blackfeet Reservation, it was clear that none of the Indians favored this idea.

Baker visited the Fort Assiniboine Military Reservation after talking with Little Bear who had told him that his people had periodically lived in the area. He concluded that the landless Chippewa and Cree should be given a small reservation within the confines of the abandoned Fort Assiniboine Military Reservation. Baker felt that a small reservation would be the first step toward assimilation and that it would remove poverty-stricken Indians from the vicinity of Montana towns.

In Montana, federal officials reported that there were approximately 100 Cree living in the Pryor Mountains on the Crow Reservation. Many of them were employed by the Crow and there was some intermarriage between the Crow and the Cree. No action was taken to remove the Cree.

Fishing and Hunting Rights:

Non-Indians established a salmon cannery on the Quillayute River in Washington and appropriated traditional Indian fishing sites. Indians were unable to obtain fishing licenses because they were considered non-citizens.

In Montana, two Blackfeet hunters were arrested for hunting in Glacier National Park. Their firearms, traps, and hides were taken from them. The Department of the Interior later instructed the Park to return these items, but the Indians were not to be allowed in the park.

It should be pointed out that while Glacier National Park did not allow Blackfeet to hunt in the park, even though their treaty clearly indicated that they had retained this right, it did allow the (non-Indian) private land owners in the park to continue to hunt in the park. In addition, government hunters were seeking to exterminate coyotes, wolves, and mountain lions within the park. The Blackfeet felt that their treaty rights included the right to hunt and fish within the park, as well as to gather wild plants, cut timber, and freely enter the area.

Education:

Long Lance (Lumbee) addressed his graduating class at the Carlisle Indian School:

“When we have gone through, for the last time as students, the brick portals of this institution, into the great world of competition, we do not wish to be designated as Cherokees, Sioux, or Pawnees, but we wish to be known as Carlisle Indians, belonging to that great universal tribe of North American Indians, speaking the same language and having the same chief — the great White Father at Washington.”

In Arizona, the Indian Office forcibly took Yavapai children from their parents so that they could be sent to Phoenix Indian School.

In Arizona, a new school was constructed for the Havasupai. The old school was destroyed in the 1910 flood. The new school was topped off with the bell from the old school.

Movies:

In California, Bison Life Motion Pictures Company made a deal with the Miller Brothers 101 Ranch Real Wild West Show in which the Wild West Show was to provide the movie company with 75 Indians and 100 cowboys. As a result, four two-reel westerns were produced: War on the Plains, The Indian Massacre, The Battle of the Red Men, and The Deserter. Sioux actor William Eagleshirt appears in War on the Plains and The Indian Massacre (both directed by Thomas Ince), and also writes the scenario for War on the Plains.

Art:

For the first time, because of the impact of the artist Cezanne, art museums began to exhibit Native American art as art.

In New Mexico, San Ildefonso potter María Martínez began to sell the black pottery which will make her and her Pueblo legendary.

María Martínez is shown above.

The Navajo Fair at Shiprock, New Mexico had an estimated $20,000 of Navajo blankets shown. Superintendent William Shelton, in his annual report, noted that the quality of Navajo weaving had improved and that-

“The demand for this product is becoming greater each year, due, no doubt, to this continued improvement.”

In California, Paiute-Miwok weaver Lucy Parker Telles began to introduce newer motifs and shapes into her baskets. Her adaptations of the traditional Miwok gift basket included some with locked lids.

Sports:

Jim Thorpe (Sauk and Fox) won the pentathlon and decathlon at the Olympics in Stockholm, Sweden. In the decathlon, Thorpe set a world record for the 110-meter hurdles. Sweden’s King Gustav V told him:

“Sir, you are the greatest athlete in the world.”

President William H. Taft said

“Your victory will serve as an incentive to all to improve those qualities which characterize the best type of American citizenship.”

Thorpe’s Indian name was Wa-Tho-Huck, which means “Bright Path.” He was the great-grandson of Chief Blackhawk.

Indian Organizations:

In Ohio, the Society of American Indians (SAI) met in Columbus. One of the issues discussed was how to speed up the assimilation process on the reservations. Arthur Caswell Parker (Seneca) formed two fraternities at the meeting: the Loyal Order of Tecumseh and the Descendants of the American Aborigines. The Loyal Order of Tecumseh allowed both active and associate SAI members to socialize and perform ritual.

In Alaska, delegates from the Haida, Tlingit, and Tshimshian communities formed the Alaska Native Brotherhood to lobby for the protection of native resources and to fight against segregation and discrimination in the territory. One of the priorities of the Alaska Native Brotherhood was citizenship and voting rights.

Reservations:

The enabling legislation that created the state of New Mexico specifically spelled out that the Indians in the state own their own land. Many non-Indians preferred to ignore Indian title to the land.

Taos Pueblo, New Mexico, asked the Secretary of the Interior to declare Blue Lake as an executive order reservation. Blue Lake is sacred to Taos Pueblo and was incorporated into the Carson National Forest in 1906. The request was denied because the Secretary of Agriculture (who is in charge of the Forest Service which administers the lake) refused to approve it.

The Zuni once again petitioned the government regarding the size of their New Mexico reservation. Zuni Governor William J. Lewis, his wife Margaret Lewis, and Lieutenant Governor Dick Tsanaha travelled to Washington, D.C. to air the tribe’s grievances.

The Indian Office filed for a water appropriation on behalf of the Ak-Chin Indian Community in Arizona which called for a total of 70,000 acre-feet annually. Non-Indians in the area were upset about the size of the reservation and about the water appropriation. Within four months of the original executive order, President Taft issued a second executive order which reduced the size of the reservation to 21,840 acres.

The government drilled a well for the Tohono O’odham village of Santa Rosa, Arizona in spite of objections from the village chief and the council. Tribal funds were used to pay for the well.

In Arizona, 15 frame houses were built by the government for the Havasupai to replace the houses destroyed in the 1910 flood. Residents were required to pay for the houses if they occupied them. The Havasupai refused to live in the houses as they were too hot in the summer and too cold in the winter.

In California, land in the Owens Valley was set aside for the establishment of reservations at Bishop, Lone Pine, and Big Pine.

In California, a fire at the Pomo village at Upper Lake destroyed several houses and the dance house. Several families moved to the Robertson Rancheria and other reservations where the government provided them with free houses.

In Montana, the Yankton Sioux on the Fort Peck Reservation selected Charles Thompson, Rufus Ricker, and Crazy Bull to travel as a delegation to Washington, D.C. In Washington, they met with the Assistant Commissioner of Indian Affairs and others to discuss their concerns regarding improvements on the reservation.

In Idaho, the federal government attempted to crack down on the unstable marriages among the Shoshone and Bannock on the Fort Hall Reservation. The Indian courts were instructed to tell the parties in divorce cases to make up their differences and live in harmony. The Indian agent noted that women tended to reject such pressure and refused to comply with the government’s request. The agent found that only when the women were sentenced to jail until they agree to go back to their husbands that they would comply.

In Wyoming, St. Michael’s Mission was established in Ethete on the Wind River Reservation. Promotional literature, used to raise money among wealthy eastern patrons, described government failure to stem the “disgraceful uncleanliness” and the high birth rate among the Shoshone and Arapaho on the Wind River Reservation. According to the brochure:

“Vice has also made appalling inroads upon them, and all this in spite of fifty years of constant supervision and help by the government, and on most reservations of long and continuous efforts on the part of the Churches.”

While a wealthy Eastern benefactress helped pay for the construction, the church school was paid for by the federal government using money which it had collected on behalf of the tribe. The new mission attempted to incorporate some aspects of Arapaho culture. One minister erected a tipi in front of his office and met with the Indians in this setting.

On Guemes Island, Washington, the Samish were forced to abandon their village and their lands because of non-Indian pressures to obtain their spring, the only source of fresh water on the island.

Leave a Reply