Cultural genocide is a concept expressed by many Native Americans to describe the deliberate destruction of American Indian languages, religions, ways of dress and housing, and interpersonal relations by the invading European powers and by the United States. Cultural genocide has led to the deaths of many American Indians either through deliberate murder or as the intended or unintended consequences of the deliberate destruction of Indian cultures. One of the classic cases of cultural genocide can be seen in California.

In 1758 Father Junípero Serra led a group of Franciscan friars north from Baja California into present-day California to establish a series of 21 missions, starting with San Diego de Alcalá in the south. The group was accompanied by a column of Spanish soldiers under the leadership of Captain Gaspar de Portolá. Robert Jackson and Edward Castillo, in their book Indians, Franciscans, and Spanish Colonization: The Impact of the Mission System on California Indians, report: “The Franciscans attempted to restructure the native societies they encountered to further Spanish colonial-policy objectives.” They also write: “One of the primary objectives of the Franciscan-directed mission program in Alta California was the transformation of the culture and world view of the Indian converts congregated in the missions.”

Christianity, for these missionaries, meant not just accepting a new religion, but it also required a totally new way of living. The sites for the missions were selected on the basis of their suitability for agriculture and ranching as well as the availability of building materials. Indian people were expected to give up their traditional economic systems and to work as slaves in European-style agriculture and ranching.

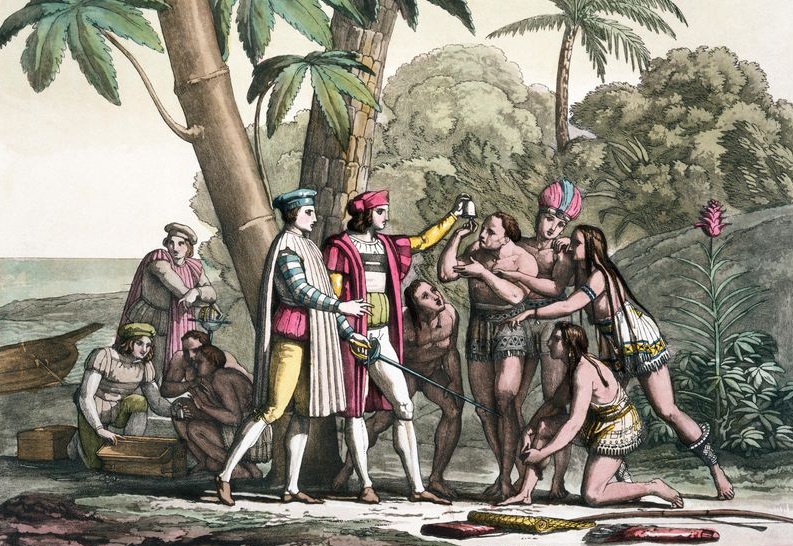

Indian people did not come joyously or freely to live and work at the new missions. In his book Where the Lightning Strikes: The Lives of American Indian Sacred Places, Peter Nabokov writes: “Soldiers snatched Indian families from outlying hamlets to convert them, change their social habits and turn them into an American peasantry.” In other words, recruitment was very similar to a slave raid. The Indian response to the missions was to flee, either in small groups or in large groups.

In his book From the Heart: Voices of the American Indian, Lee Miller notes: “Spain continued to operate under the European assumption that non-Christian nations were base and immoral, and the church was obligated to effect conversion.” Furthermore, the Spanish, according to anthropologist Edward Castillo (1978a: 99): “were steeped in a legacy of religious intolerance and conformity featuring a messianic fanaticism accentuating both Spanish culture in general and Catholicism in particular.”

The Franciscans sought to set up a utopian Christian community among the Indians. Malcolm Margolin, in his book The Ohlone Way: Indian Life in the San Francisco-Monterey Bay Area, writes that the Indians: “would be weaned away from their life of nakedness, lewdness, and idolatry. They would, under the gentle guidance of the Franciscan fathers, learn to pray properly, eat with spoons, wear clothes, and they would master farming, weaving, blacksmithing, cattle raising, masonry, and other civilized arts.”

For this utopian Christian community, the Indians were to live at the mission. Unmarried males and females were confined to separate quarters to prevent any sexual relationships. The Indians were told who they could marry and what kind of clothing they were to wear. For most Indians the mission communities were death camps. Writing in the Handbook of North American Indians Sherburne F. Cook and Cesare Marino note: “the physical confinement and the restriction of social as well as sexual intercourse was completely contrary to native custom and acted as a powerful source of irritation.”

Father Junípero Serra, who is revered by many of today’s Catholics, is described by Malcolm Margolin as being “driven by inner torments and a quest for personal martyrdom.” He lashed and burned his flesh before his congregations. Anthropologist Eve Darian-Smith, in her book New Capitalists: Law, Politics, and Identity Surrounding Casino Gaming on Native American Land, describes him this way: “He was a man of extreme conviction in his commitment to convert California Indians to Catholicism and make them productive citizens of the Spanish colonial state.”

The Franciscans asked the Indians who came to see them to be baptized, even if they did not understand the meaning of this European ceremony. Once baptized, they could be held at the missions against their will. Soldiers were stationed at the missions to capture those who tried to escape. Escape attempts were severely punished by the Franciscans.

The Franciscan missions were slave plantations, requiring the Indian people to work for the Spanish under cruel conditions. Most of the Indians died in the new mission environment because of brutality, malnutrition, and illness. One early visitor to the missions remarked about the Indians that “I have never seen one laugh.”

In 1948, the United Nations formally defined genocide and classified it as a crime against humanity. Many of the actions of the Franciscans under Serra can be considered acts of genocide under the U.N. definition.

Today, many Native Americans, particularly those who have a California Indian heritage, consider Serra to have been a brutal oppressor whose actions killed many thousands and helped to destroy ancient cultural heritages. While we don’t know for sure if Serra personally killed anyone, his actions led to death, destruction, pain, suffering, slavery, and poverty.

The Catholic Church appears to honor and celebrate the brutality and cultural genocide promoted by the Franciscan priest: he will be declared a Saint by Pope Francis in September of 2015. Some Catholics, such as Los Angeles Archbishop Jose Gomez, applaud the creation of this new saint.

Leave a Reply