With the formation of the United States in the late eighteenth century, policies toward American Indians generally followed the British colonial model in which Indians, like wolves, bears, and trees, were viewed as impediments to the taming of the wilderness. The British did not seek to incorporate American Indians into their colonial culture, but to isolate and segregate them and/or to exterminate them.

Following this philosophical model, the United States established Indian reservations as a way of removing Indians and freeing their lands and natural resources (i.e. mining and timber) to be developed by non-Indians. One of America’s founding fathers, Thomas Jefferson, suggested that Indians should be removed from the United States and placed on lands west of the Mississippi River.

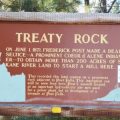

There were three basic ways in which reservations could be established: by treaty, Presidential executive order, and Congressional action.

The United States could negotiate a treaty with an Indian nation in which the Indian nation would reserve a portion of its traditional homeland for its exclusive use or agree to move to other lands which would be reserved for its exclusive use. Under the U.S. Constitution, Indian tribes were viewed as sovereign nations and thus dealings with them, just as with over sovereign nations, had to be on the federal level. In 1871, however, Congress–upset by the cost of the treaties and the need to pay the Indians for their lands– attached a rider to the appropriations bill for the Indian Department which stated that hereafter no Indian tribe shall be recognized as an independent nation with whom the United States may contract by treaty.

Reservations could also be established by Presidential executive order and by Congressional action.

The well-known Indian-fighter General William T. Sherman once defined a reservation as: “a tract of land entirely occupied by Indians and entirely surrounded by white thieves”

Anthropologist Anthony Wallace, in his The Death and Rebirth of the Seneca, writes: “The reservation system theoretically established small asylums where Indians who had lost their hunting grounds could remain peacefully apart from the surrounding white communities until they became civilized. It actually resulted, however, in the creation of slums in the wilderness, where no traditional Indian culture could long survive and where only the least useful aspects of white culture could easily penetrate.”

Some reservations were run like concentration camps where the Indian inmates were seen as prisoners. Reservation Indians were viewed as being incompetent in managing their own affairs. Boarding school superintendent Edwin Chalcraft, in his biography Assimilation’s Agent: My Life as a Superintendent in the Indian Boarding School System, reports that “…Government Regulations provided that Indians shall not leave their reservations without a written pass from the officer in charge.”

In describing his experience with the Pine Ridge Reservation in the 1890s, Sioux physician Charles Eastman, in Light on the Indian World: The Essential Writings of Charles Eastman (Ohiyesa), reports: “An Indian agent has almost autocratic power, and the conditions of life on an agency are such as to make every resident largely dependent upon his good will.”

Corruption in the administration of Indian reservations was wide-spread. Indian reservations provided ample opportunity for fraud. First, there were the Indian agents on the reservation. Poorly paid and untrained for the job, many Indian agents saw this as an opportunity to get rich. It was not uncommon for the Indian agent to have a store in an off-reservation town which sold the goods that had been intended as annuities for the reservation and instead were unlawfully re-directed to his own store.

Getting the goods to the reservation required shipping and shipping agents generally overstated the millage involved. Suppliers who provided beef generally provided ill, underweight cows and charged for good, healthy animals. Suppliers saw the reservations as good places to send spoiled or unsalable goods. Money was made by all, and the Indians received very little of what they had been promised by the government. Historians Robert Utley and Wilcomb Washburn write: “From factory to agency warehouse, corrupt alliances enriched government officials and suppliers and penalized the Indians in both quantity and quality of issue.”

One of the primary goals of the United States government with regard to Indians was to convert them to Christianity, primarily Protestant Christianity. As it became obvious to all that the Indian Service was corrupt and failing to assimilate Indians, it seemed natural to turn to missionaries and churches for the solution. In his 1870 message to Congress, President Ulysses Grant proposed turning the administration of reservations over to Christian groups. With no regard for aboriginal religious practices, it was assumed that all Indians should be forced to become Christian as a part of their assimilation into American culture.

In accordance with President Ulysses Grant’s Peace Policy, the Secretary of the Interior allocated 80 reservations among 13 Christian denominations. Catholic historian James White, writing in Chronicles of Oklahoma, reports: “By the terms stated in Grant’s policy, namely that missions should be allocated among the missionaries already at work there, Catholic officials expected to receive thirty-eight missions; instead they were accorded only eight, all of them in either the Rio Grande valley or the Pacific Northwest.” Subsequently, Catholic missionaries began to be ordered off certain reservations.

Another often-stated goal of the reservations was to turn Indians into farmers, ignoring the fact that most Indian nations had been farming prior to the European invasion and the early colonists managed to survive because of Indian agriculture. On the other hand, non-Indians were given the best farming lands and Indian reservations were generally located in areas that were not suitable for agriculture. In other words, reservations tended to be located in areas which could not be farmed.

Indians were not allowed to engage in mining. The Commissioner of Indian Affairs wrote in 1872: “It is the policy of the government to segregate such [mineral] lands from Indian reservations as far as may be consistent with the faith of the United States and throw them open to entry and settlement in order that the Indians may not be annoyed and distressed by the cupidity of the miners and settlers who in large numbers, in spite of the efforts of the government to the contrary, flock to such regions of the country on the first report of the gold discovery.”

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, the United States began to break up Indian reservations and open them up for non-Indian settlement. This was formalized with 1887 General Allotment Act (also known as the Dawes Act). The idea of holding land in common was seen as uncivilized, un-Christian, and a barrier to civilization. Indians were first encouraged and then required to obtain individual ownership of land. The idea of owning land in severalty became almost an obsession of the late nineteenth century Christian reformers. They were convinced that such a policy would force the Indians to become more American. Historian Clifford Trafzer, in his introduction to American Indians/American Presidents: A History, reports: “By dividing tribal reservation lands into small parcels for individual Indians, reformers believed that allotment would imbue Native people with respect for private—rather the tribal—property, and help Indians assimilate into mainstream American culture.”

The result of this policy was to force American Indians into poverty and to create wealth for non-Indians. American capitalists and large corporations acquired Indian resources.

Leave a Reply