In its dealings with Indian Nations, the United States often imposed an alien form of government on them. This government was not a democracy, but usually a dictatorship in which the leaders were chosen by the United States based on their willingness to follow the dictates and changing whims of the U.S. government. For a short period of time in the late nineteenth century, one “tribe” was allowed an experiment in self-government. That “tribe” was the Chiricahua Apache.

Some Background:

In the late 1300’s and early 1400’s groups of hunting and gathering Athabascans began arriving in the Southwest from the far north in Canada. These were the ancestors of the Navajo and Apache peoples.

When the Spanish entered New Mexico, they recorded that the Tewa (a pueblo group) referred to one of the neighboring tribes as Navahú in reference to large areas of cultivated lands. This is in reference to the Navajo practice of dry-farming in arroyos and cañadas. The Tewa also referred to these newcomers as Apachü, which means strangers and enemies. The Spanish would later refer to these people as Apache de Navajó meaning the Apaches with the great planted fields.

There are six major divisions of the Apache: the Western Apache, Chiricahua, Mescalero, Jicarilla, Lipan, and Kiowa-Apache.

The Chiricahua Apache were in the mountains of southeastern Arizona. The term “Chiricahua” was coined by an anthropologist to refer to the autonomous tribes living in or near the Chiricahua Mountains. Tribal historian Michael Darrow reports that there were four independent political units in this area: Chíhéne, Chokonene, Bidánku, and Ndé’ndaí.

Like many other Indian tribes, there was no single overall Chiricahua leader: each of the local groups had its own political structure. Historian Robert Utley writes of the Chiricahua in his book A Clash of Cultures: Fort Bowie and the Chiricahua Apaches: “They felt little tribal consciousness and never came together as a tribe.”

According to anthropologist Norman Bancroft-Hunt in his book North American Indians: “People were free to follow the leader they chose, with the consequence that Apache bands were small and mobile, composed of people with a strong sense of independence and individual freedom.”

The lack of a centralized government or single leader created confusion for the United States government. Writing about the Chiricahua Apache, anthropologist Morris Opler, in an article in Anthropology of North American Tribes, reports: “the Chiricahua found, to their great discomfort, that the white officials assumed what no Apache would admit – that an agreement with the leader was binding upon the whole group.” Chiricahua leaders led through advice, persuasion, and example. They served as leaders only as long as their leadership proved successful.

While many non-Apache scholars and popular writers have labeled the Apache as a fierce, war-like people, in actuality warfare was not glorified as it was in some other culture areas. Chiricahua Apache tribal historian Michael Darrow, in a chapter in We, The People: Of Earth and Elders—Volume II, writes: “In our tribe we don’t have any military societies or Dog Soldiers like the Plains Indians. We didn’t have anything vaguely resembling that. In our tribe you didn’t attain special status by participating in something like that.” Darrow also writes: “In our tribe, you didn’t get an eagle feather for each enemy smacked with a coup stick or killed. You didn’t get awards for battle accomplishments because they generally avoided fighting as much as possible.”

The Experiment:

In 1872, General Oliver Otis Howard agreed to attempt to contact Chiricahua Apache leader Cochise without a military escort. Howard and four others ignited a ring of five fires to show that five men had come in peace. Eventually two boys appeared at the Americans’ camp and led them to a secluded mountain valley containing an Apache camp. That evening, Cochise appeared in the camp.

Howard and Cochise bargained for ten days. Howard wanted the Apache to settle on a reservation on the Rio Grande, but Cochise asked to keep the Chiricahua homeland at Apache Pass. Historian Robert Utley reports: “Eventually Howard bowed to Cochise’s wish to remain in his home country and proposed a reservation embracing a large part of the Chiricahua Mountains and the adjoining Sulphur Springs and San Simon Valleys.” Under the agreement, the Chiricahua were to police themselves without army supervision.

Many high-ranking members of the U.S. Army, including Generals Crook and Schofield, were not happy with the agreement. In The Indian Historian D.C. Cole writes: “The military was particularly incensed by the exemption of the reservation from military supervision.”

However, the Department of the Interior confirmed the site and the reservation was established by Presidential Executive Order. Without any major interference from the federal government, the Chiricahua peacefully governed themselves on their reservation.

In 1874, Chiricahua Apache leader Cochise died. His body was prepared in a traditional way and then taken to a deep fissure where it was lowered into the depths. His favorite horse and dog were killed and were also buried in the fissure. Taza, the son of Cochise, was selected by the Chiricahua to become their new chief. Historian Robert Utley reports: “But Taza lacked his father’s force and vision, and increasingly the Chiricahuas drifted without the strong leadership on which the outcome of the reservation experiment depended.”

In 1875, the Chiricahua Apache were accused of a number of raids. D.C. Cole writes: “The military accused the reservation Apache of raids against travelers, which were in reality the work of Cochise County white outlaws. The Mexican authorities protested Chiricahua raids in Sonora, which were in all probability the work of Mexican-based Apache of the Sierra Madres.”

In response, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs suspended services to the reservation. Investigations later cleared the Chiricahua of all charges, but the investigators recommended the removal of the Chiricahua to the San Carlos reservation in Arizona or to New Mexico in order to prevent any future incidents.

In 1876, two non-Indian whiskey sellers were illegally selling whiskey on the Chiricahua Apache reservation when they were killed by the Chiricahua. In response, and ignoring the fact that the incident was caused by non-Indians engaging in illegal activities, the Americans used this as an excuse to seize the reservation and move the Chiricahua to the San Carlos reservation. The Chiricahua reservation was abolished by Presidential Executive Order. D.C. Cole writes: “Ended, perhaps forever, was Apache faith in the honor and good intentions of the United States government. Also gone was a United States sanctioned experiment in Apache self-government by means and upon lands of their own choosing.”

The experiment in Chiricahua self-government ended as the Chiricahua bands were removed to the San Carlos Apache Reservation. The people had planted a great deal of corn which they were forced to abandon. After they moved, their houses were burned and their corn fields destroyed.

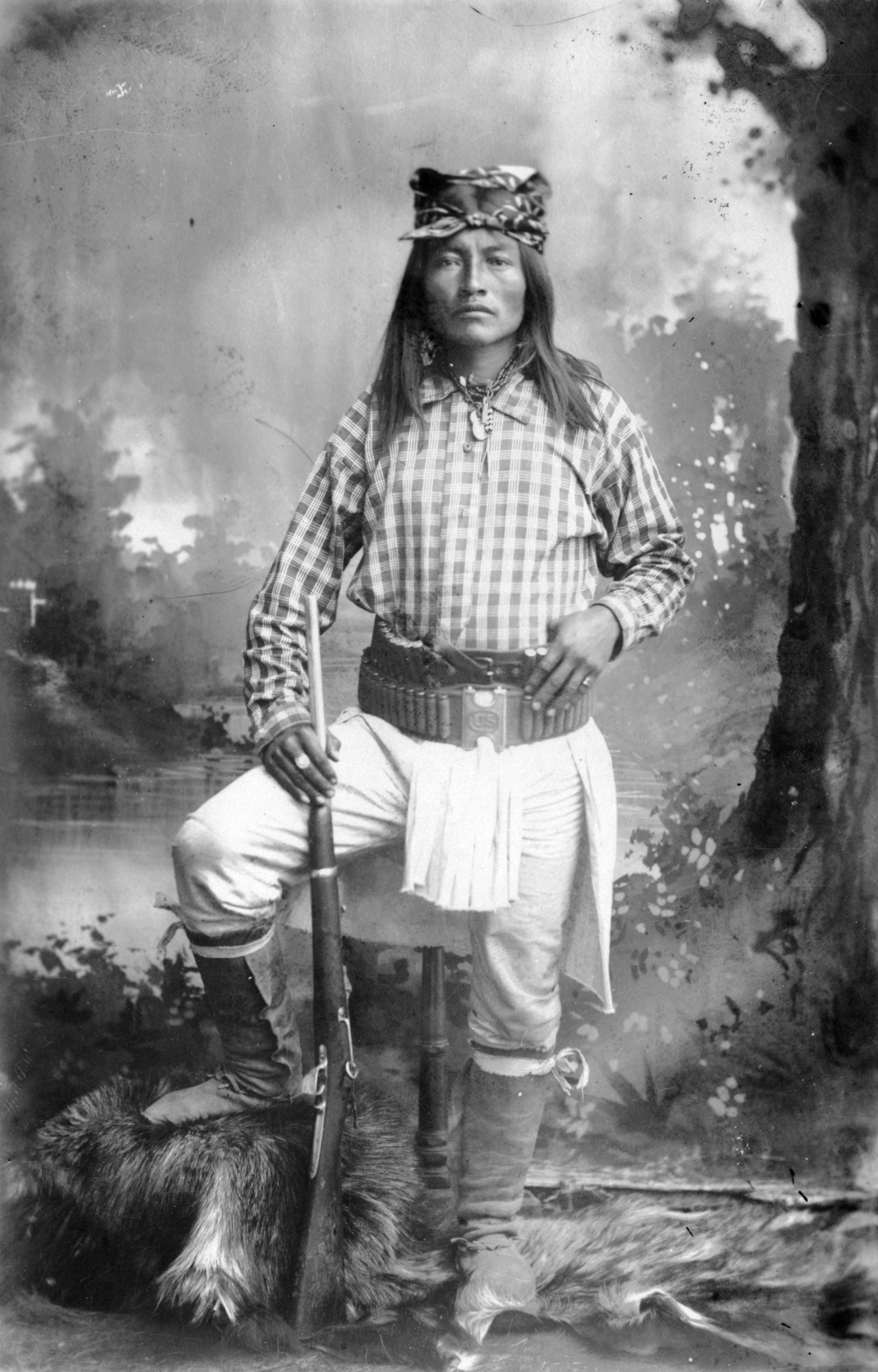

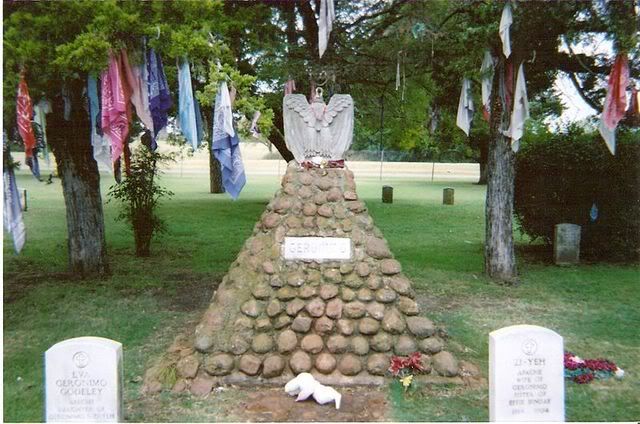

Not all of the Chiricahua followed Taza to San Carlos. A number of them joined the Nednhi Chiricahua under the leadership of Juh in the Sierra Madre Mountains of Mexico. Among those who went to Mexico is Geronimo. From here the Apache began a series of raids on American settlements in Arizona and New Mexico.

After moving to the San Carlos Reservation, Taza and several others joined an entourage organized by the Indian agent for the reservation which toured in several Eastern cities and put on a scripted “wild west show.” The show, however, was not successful and stopped performing after Cincinnati.

Leave a Reply