The Cherokee in 1817

When the Europeans began their invasion of the Americas, the Cherokee were an agricultural people whose villages could be found throughout the American Southeast. By the first part of the nineteenth century, the Cherokees had had enough experience in dealing with the American government that they understood that they needed to have a unified government. Summarized below are some of the Cherokee events of 1817.

In Tennessee, Cherokee leader Major Ridge took John Ross to a private meeting with tribal elders. Ross was informed that he was to be appointed to the National Committee. In his book Toward the Setting Sun: John Ross, the Cherokees, and the Trail of Tears, Brian Hicks writes:

“It was Ross’s mind and his education that appealed to the chiefs, traits that, ironically, he had developed in white schools.”

In Georgia, General Andrew Jackson addressed the Cherokee National Committee. He told the Cherokee that now was the time to move to the west, for if they waited the land would be given to non-Indian settlers. Those who did not move were to be placed under the control of the government. Brian Hicks reports:

“Jackson offered the Cherokees two unattractive options: they could live under the laws of the United States or move west. It was an ambitious power play and, by most accounts, a bluff. The general had no authority to make such demands, but he had the gall to call his proposal ‘justice for all.’”

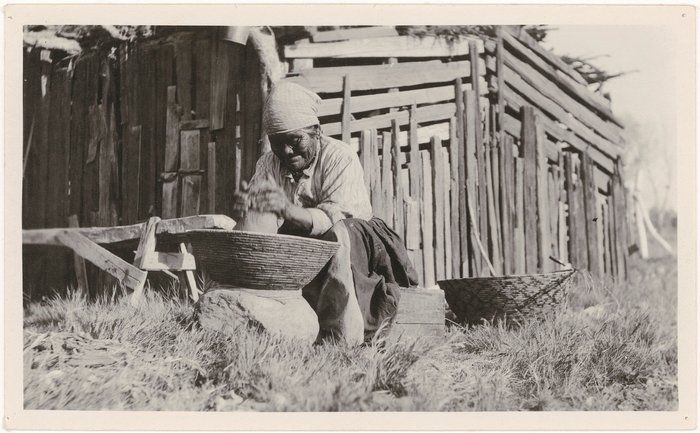

The eighty-year-old Nancy Ward, the niece of the eighteenth-century chief Atakullakulla, addressed the council. Brian Hicks reports:

“She assured her people the creator had given them this land and urged the chiefs not to sell any more land but to ‘keep it for our growing children.’ Her words had a minimal effect on the most anxious Cherokees.”

John Ross was delegated the task of drawing up a response to Jackson. In this response, he called the Cherokee “a free and distinct nation” and noted that the American government’s policy toward the Cherokee was simply about friendly intercourse in trade. Following this rebuttal, Path Killer dismissed General Jackson without giving him an opportunity to respond.

In Georgia, General Andrew Jackson bypassed the Cherokee National Council. He drew up a treaty and persuaded a group of lower town chiefs to sign it. The treaty called for the Cherokee to move to Arkansas or to remain in the east by taking land allotments and living under state laws. Those signing the removal treaty included Glass and Tuckasee. When Jackson turned the treaty in to the War Department, he neglected to tell them that it had not been approved by the Cherokee National Council or by the Cherokee Principal Chief.

According to historian Frances Paul Prucha, in his book American Indian Treaties: The History of a Political Anomaly:

“This Cherokee removal treaty of 1817 severely divided the Indians, and those who decided to migrate charged persecution from the other faction, but large numbers of Cherokees, nevertheless, moved west.”

Initially, more than 700 Cherokee enrolled for removal and 1,102 actually migrated to the west.

In Georgia, the Cherokee National Council dismissed the lower town chiefs who signed the removal treaty drafted by General Andrew Jackson. A delegation carefully selected by Path Killer and Charles Hicks was sent to Washington to inform the government that the treaty had been negotiated with a minority of chiefs and did not have the approval of the Cherokee nation. A spokesman for the War Department simply informed them that the Secretary of War had already arranged for boats to transport the Cherokee west of the Mississippi.

In Georgia, the Cherokee Council voted to establish a standing committee to manage the nation when the Council was not in session.