The earliest period of human occupation in the Northern Great Basin region of Oregon is called the Paisley Period by archaeologists. The period, which is tentatively dated from about 15,700 years ago to 12,900 years ago, is named after the Paisley 5 Mile Point Caves site (35LK3400) near Summer Lake.

During the Paisley Period, Native peoples in Oregon adapted to the Northern Great Basin environment at a time when the ice ages were ending and the region was undergoing dramatic climatic and environmental changes. Jeff LaLande, writing for The Oregon History Project, describes the environment: “By the time of these earliest arrivals, the region’s glaciers had melted into small remnants, and many of the great Ice Age lakes had begun to shrink into shallow but plant- and animal-rich lakes, marshes, and wetlands.”

The people at this time were hunting and eating bison, camelids, horse, deer, mountain sheep, pronghorn antelope, and sage grouse. They were gathering a wide variety of different plants, including goosefoot (Chenopodiacea sp.), sunflower, cactus, rose hips, and desert parsley. They were making and using a variety of stone and bone tools.

While the Paisley Caves site is the best-known of the most ancient Oregon sites, there are a number of other sites which also date to this era.

Dietz Site:

Located in Central Oregon’s Alkalai Basin to the east of the Fort Rock area near Wagontire, the Dietz Site (35LK1529) dates to the end of the Paisley Period. This is an interesting site as it represents a Clovis intrusion into the region. At one time the Clovis tradition with its characteristic fluted points was thought to represent the earliest people in North America. In their book Oregon Archaeology, Melvin Aikens, Thomas Connolly, and Dennis Jenkins write: “The Dietz site is currently one of only three recorded Clovis-era sites in Oregon where multiple artifacts have been recovered, though Clovis fluted points are reported widely as isolated surface finds.”

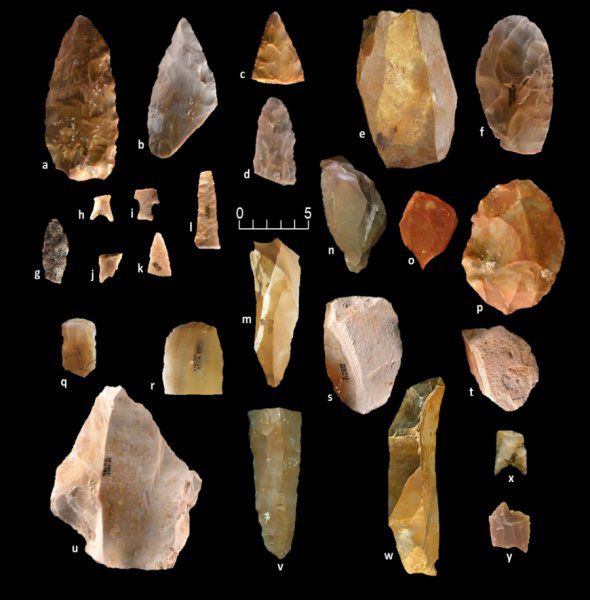

The Clovis materials at the site have been dated to about 13,200 years ago. The Clovis artifacts recovered at the site include fluted points, flute flakes, and biface projectile point blanks. Horse Mountain, located about a mile from the site, is the source of much of the obsidian used for the stone tools.

In addition to the Clovis materials, the archaeologists also found large stemmed and shouldered points associated with the Western Stemmed tradition. Also associated with these artifacts were some grinding stones. Some archaeologists feel that the Clovis and Western Stemmed artifacts represent two different groups of people. The Clovis materials generally represent a narrowly focused hunting adaptation, while the Western Stemmed is a more generalized gathering and hunting adaptation. Melvin Aikens, Thomas Connolly, and Dennis Jenkins write: “Based on what we know of broader associations, the Western Stemmed people attested at the Dietz site may have been more broad-spectrum and opportunistic in their subsistence strategies, and the Clovis folk relatively more focused on following and hunting large game.”

The Western Stemmed tradition is older than Clovis in the region.

Sage Hen Gap:

Another Clovis site is located north of the Dietz site. Artifacts found at the Sage Hen Gap site (35HA3548) include fluted points, a single Western Stemmed point, fluting flakes, gravers, and lots of obsidian flakes. Melvin Aikens, Thomas Connolly, and Dennis Jenkins write: “The site appears to have been a good ambush location for hunting large game as they funneled down from higher terrain through narrow, steep wash bottoms cut into a high ridge.”

Catlow Cave:

Some ninety miles south of Burns, in the southern end of the Catlow Valley, Luther Cressman found some extinct Pleistocene horse bones at Catlow Cave in the late 1930s. Cressman, lacking any precise scientific dating methods at this time, suggested that this site had been occupied at the same time as the Paisley Caves. Human bones were also found at this site, but they were found in gravel so there was no way to prove their age. In the late 1970s, plans were made for a reinvestigation of the site, but the site was destroyed by mining and artifact collectors before any scientific excavations could be carried out. Melvin Aikens, Thomas Connolly, and Dennis Jenkins write: “This sorry event took place in defiance of signs and barriers erected at the mouth of the cave by the Bureau of Land Management to safeguard its archaeological evidence. The human bones themselves, never directly radiocarbon dated, were repatriated and reburied under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990.”

Fossil Lake Camelid Kill Site:

Located at the northern end of the Fort Rock basin, the Fossil Lake Camelid Kill Site (35LK525) contained camelid bones (probably Camelops hesterenus) and fragments of a projectile point. The collagen from the bones was radiocarbon dated to about 12,000 years ago.

Leave a Reply