In 1846, the United States took control of New Mexico and Arizona. The United States Army under the leadership of General Stephen Watts Kearny occupied the territory which had been acquired from Mexico. One of the major priorities of the new regime was to “pacify” the Navajo who had been raiding against the Spanish settlements in the area. However, instead of bringing peace, federal government actions often brought increased warfare. The American army made it clear that they intended to side with the European settlers without examining the causes for the hostilities. The army refused to recognize that the Indians had often been the victims of unfriendly European settlers.

In an 1846 letter to Indian Commissioner William Mediall, Charles Bent, an Indian trader, described the Navajo as

“an industrious, intelligent and warlike tribe of Indians who cultivate the soil and raise sufficient grain for their own consumption and a variety of fruits.”

He also noted that they manufactured blankets and woolen goods. Other traders during this time observed that Navajo blankets were coveted trade items among other Indians, such as the Cheyenne.

When the Navajo leader Narbona first heard about the new American regime, he decided to travel to Santa Fe to obtain firsthand information about these new soldiers. He took with him only a few of his older councilors and traveled at night. Near Santa Fe they remained hidden from the soldiers so that they could safely watch the activities without being discovered. After observing the soldiers, they returned home without making any contact with the Americans. On the journey home, all agreed that Navajo warriors would be unable to defeat the American soldiers. They decided that it would be well to establish friendship with the Americans.

The first treaty council between the United States and the Navajo was held to negotiate the Bear Springs (Ojo del Oso) Treaty. Navajo leaders Narbona, Zarzilla (Long Earrings), and José Largo met with an American force of 350 soldiers. The eighty-year-old Narbona was suffering from an attack of influenza and was brought to the council on a litter slung between two horses. As was typical with American negotiations with Indians, the Americans had no concept of Navajo government. The Americans assumed that all people who spoke some dialect of Navajo must belong to a single political entity ruled by an authoritative dictator or monarch. They did not understand that the Navajo were really numerous independent, autonomous bands. Before the American troops had returned to the Rio Grande, the Navajo were again raiding near Albuquerque. These bands, not represented at the council, were unaware of the treaty, and, if they had been aware of it, would not have viewed it as binding them. The Treaty of Bear Springs was never ratified by the U.S. Senate.

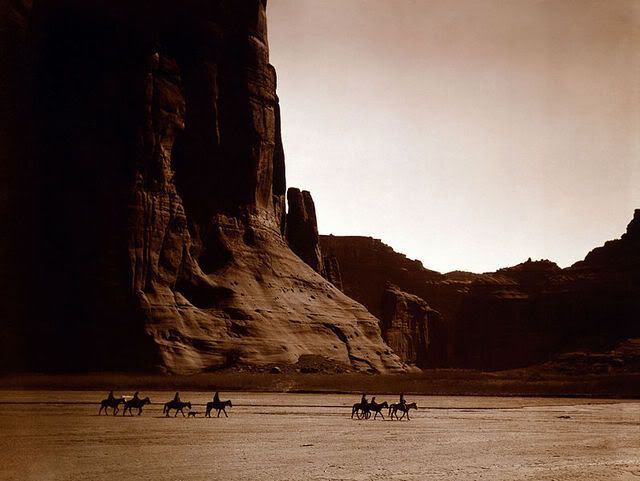

In 1848, several Navajo leaders and the United States signed the Newby Treaty. The following year, when it became evident that the treaty was not working, the Americans, under the leadership of Lieutenant Colonel John M. Washington, sent an expedition to negotiate another treaty at Canyon de Chelly. While on the way to Canyon de Chelly, the Americans met several Navajo leaders in the Chuska Valley. The Americans held council with Navajo leaders Narbona, Achuletta, and José Largo. The Navajo leaders were asked to attend a council to sign a treaty with the United States. Narbona and José Largo indicated that they would not be able to attend and designated Armijo and Pedro José to attend in their place.

As the Navajo leaders were leaving, there was a dispute over an allegedly stolen horse in which the Americans told them that they must turn over one of the best horses. The skirmish with the Americans resulted in the immediate death of 16 or 17 Navajo, with several others dying later from wounds received in the battle. The elderly chief Narbona was mortally wounded but lived long enough to return to his hogan and say goodbye to his family. Narbona was probably the most respected Navajo leader at this time and had tried valiantly to establish peace between the Navajo and the United States.

In 1849, four Navajo medicine men made the sacred journey to Tohe-ha-glee (Meeting Place of Waters) to consult with the Page of Prophecy. After making the proper offerings, they read the marks in the sand which are the messages from the Holy People. The marks indicated a journey to a distant place. Other marks indicated many burials.

In the same year, the blind Navajo prophet Bineah-uhtin, a medicine man who saw with his mind, attended a War Chant where he came into contact with some young Navajo warriors. He told them:

“The day will come when your enemies will drive you out of your homeland, and you will go to a barren country where the corn will not grow and your sheep will eat poison weeds and die. Many of your people will starve, and others will be killed so that only a few will survive, and in all these wide cornfields there will be nothing alive excepting the coyotes and the crows.”

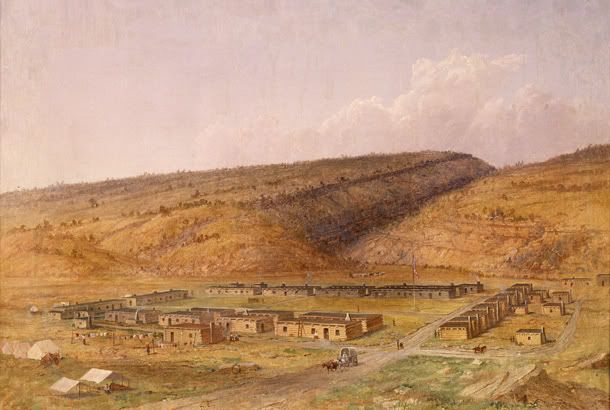

In 1851, the army established Fort Defiance (called Hell’s Hollow by the soldiers) for the express purpose of subduing the Navajo. While the American Indian agent was encouraging peaceful relations with the Navajo, the military was pushing for confrontation.

Congress appropriated $30,000 in 1854 for the purpose of negotiating treaties with the Apache, Navajo, and Ute in New Mexico. The Commissioner of Indian Affairs felt that the solution to the Indian “problem” was to extend the reservation concept into New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah.

In 1855, at Laguna Negra, New Mexico, a treaty council was held with the Navajo. About twenty chiefs were in attendance and Zarcillos Largos (Long Earrings) spoke for them. In the midst of the conference Zarcillos Largos told the Americans that he had grown too old to lead his people and he asked the Navajo headmen to select another to speak for him. Manuelito was selected as the new leader. The Americans promised the Navajo a reservation and annuity payments. Twenty-seven Navajo chiefs made their marks on the treaty and received presents. The Senate, balking at the monetary cost, refused to ratify the treaty.

In 1858, Navajo leader Manuelito pastured his horses and cattle in the army hay camp at Fort Defiance. Army troops then slaughtered 48 head of his cattle. The Navajo, in response, killed the black slave of an army officer. This began a new series of wars between the Navajo and the Americans.

In 1858, the American army imposed a new treaty on fifteen Navajo headmen at Fort Defiance. The Americans blamed the Navajo for the conflict and exacted a number of concessions from them. However, neither side was prepared to honor the treaty. Relations continued to deteriorate.

In 1861, a group of Navajo were having a peaceful horse race with soldiers at Fort Fauntleroy when the soldiers massacred 15 Navajo, including women and children. The incident started when the Navajo accused the officers of cheating. As a result, relations with the Navajo become strained and the only Navajo who remained at the post were the mistresses of some of the officers. The commanding officer then sent these women as emissaries to the Navajo. Army officials were willing to exploit the sexual relations between Navajo women and army officers in moments of crisis.

In 1861, a large Navajo war party under the leadership of Manuelito and Barboncito attacked Fort Defiance and nearly overran it.

In 1863, General Carleton issued an ultimatum to the Navajo: they were to peacefully transfer to the reservation at Bosque Redondo or be treated as hostile. Colonel Kit Carson began to wage a “scorched earth” campaign against the Navajo. The plan, devised by General Carleton, called for all male Navajo to surrender or be shot. This resulted in the Navajo Long Walk, their imprisonment, and having the Treaty of Bosque Redondo forced upon them in 1868.

Leave a Reply